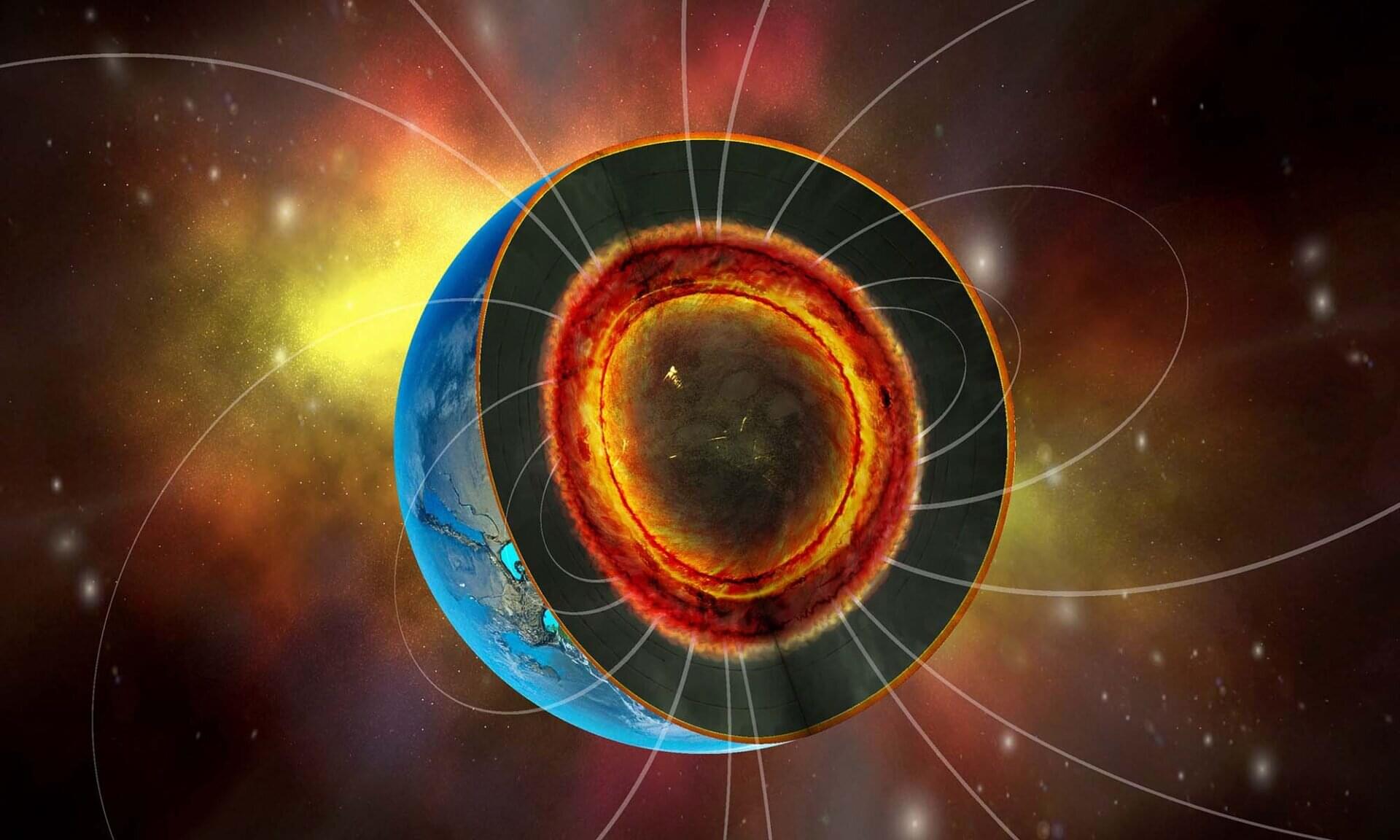

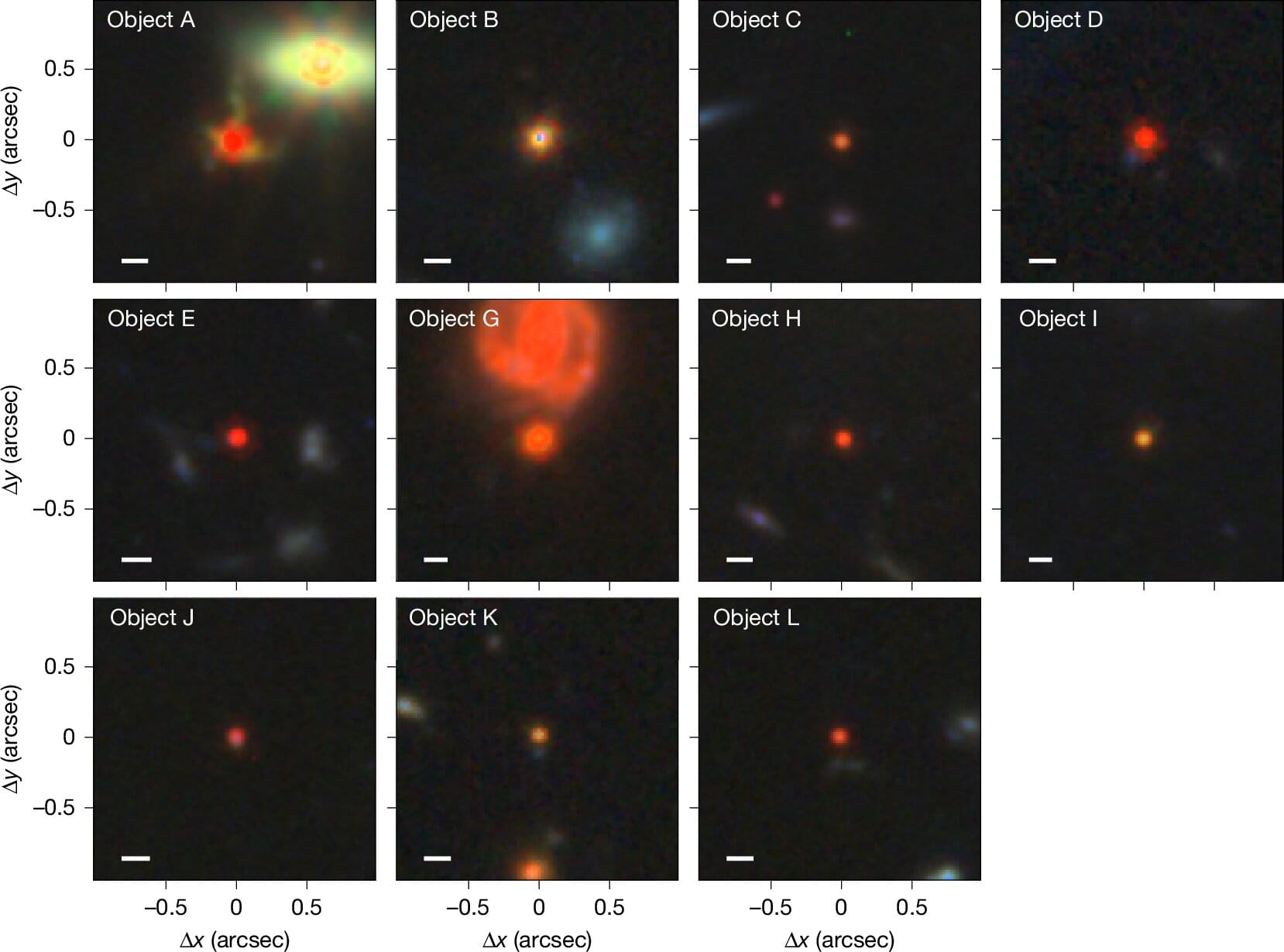

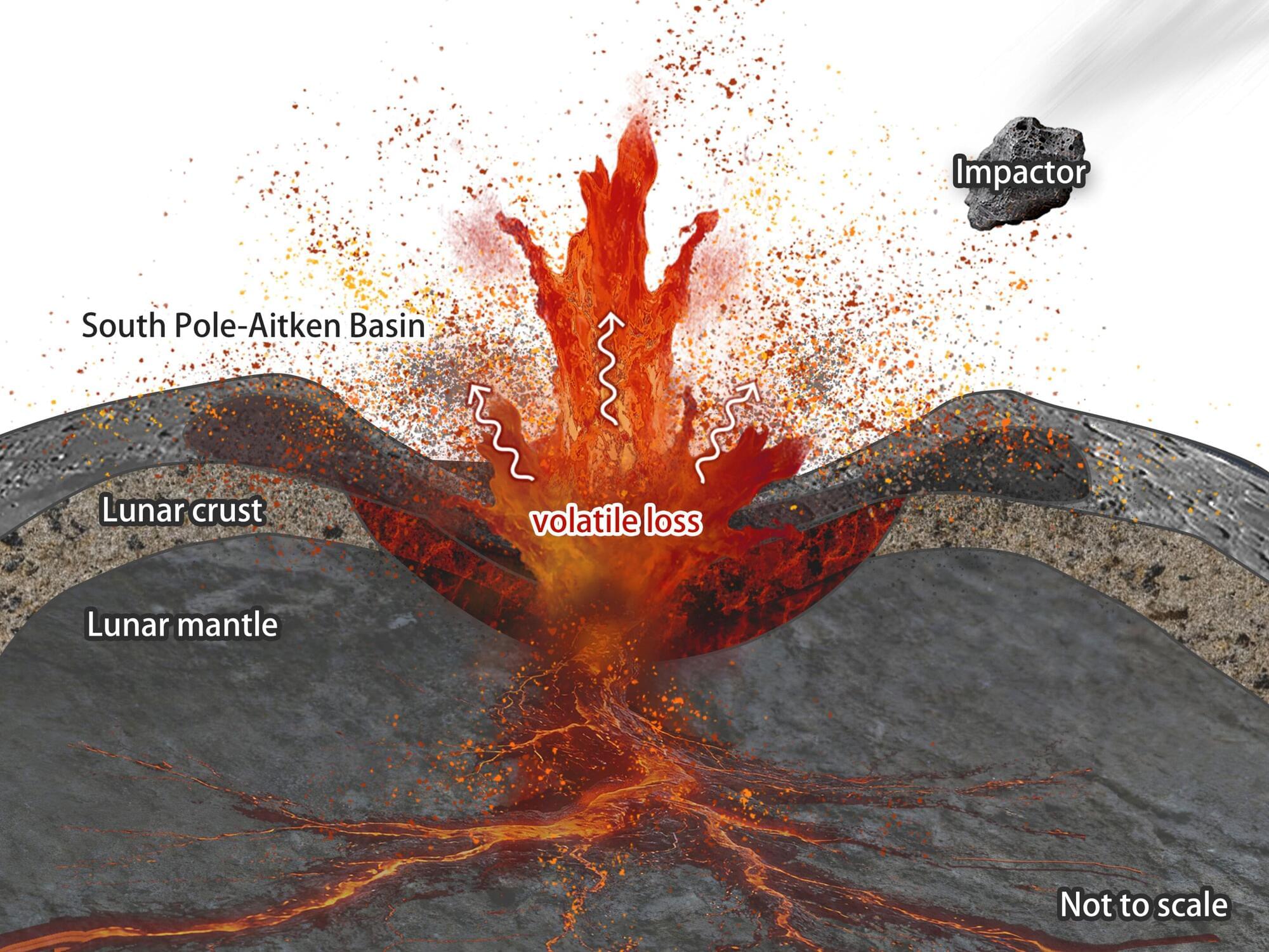

Deep beneath the surface of distant exoplanets known as super-Earths, oceans of molten rock may be doing something extraordinary: powering magnetic fields strong enough to shield entire planets from dangerous cosmic radiation and other harmful high-energy particles.

Earth’s magnetic field is generated by movement in its liquid iron outer core—a process known as a dynamo—but larger rocky worlds like super-Earths might have solid or fully liquid cores that cannot produce magnetic fields in the same way.

In a paper published in Nature Astronomy, University of Rochester researchers, including Miki Nakajima, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, report an alternative source: a deep layer of molten rock called a basal magma ocean (BMO). The findings could reshape how scientists think about planetary interiors and have implications for the habitability of planets beyond our solar system.