Using artificial intellgence to find possibilities while humans gauge their significance is proving to be a powerful new form of scientific discovery.

Many modern science fiction movies tend to use the veneer of science fiction as a way to plug potholes or feature elaborate explosions and action. There’s always a time-travel portal to stand in as the deus ex machina, and some advanced robot or alien who only seems interested in killing everyone.

I like those movies as much as the next fella. But some filmmakers do make a sincere effort to imagine other realities and technologies that inspire in the way classic science fiction does. It doesn’t mean the films have to be the on-screen equivalent of reading an MIT paper on quantum entanglement or something, just that they spin a decent yarn inspired by actual science.

The below are a few slightly less commercial selections, instead of obvious choices like Interstellar or 2001 or Chef, that science fiction movie where Jon Favreau dates both Scarlett Johnasson and Sofia Vergara. That’s the future I want.

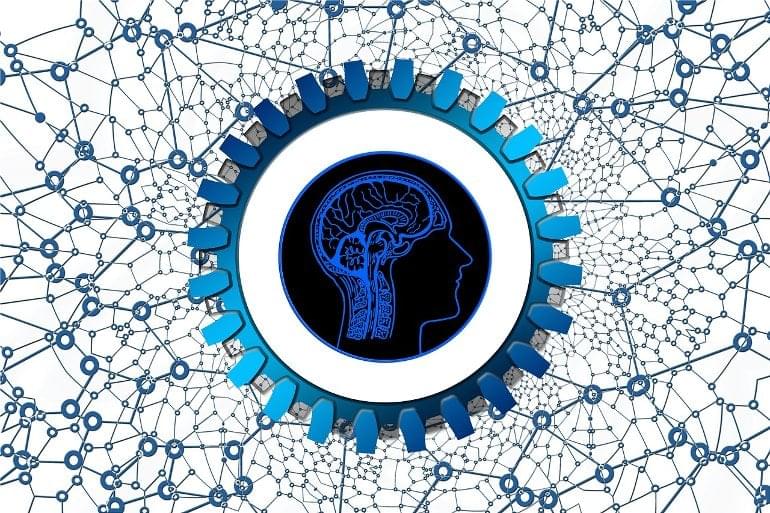

Summary: Study suggests quantum processes are part of cognitive and conscious brain functions.

Source: TCD

Scientists from Trinity College Dublin believe our brains could use quantum computation after adapting an idea developed to prove the existence of quantum gravity to explore the human brain and its workings.

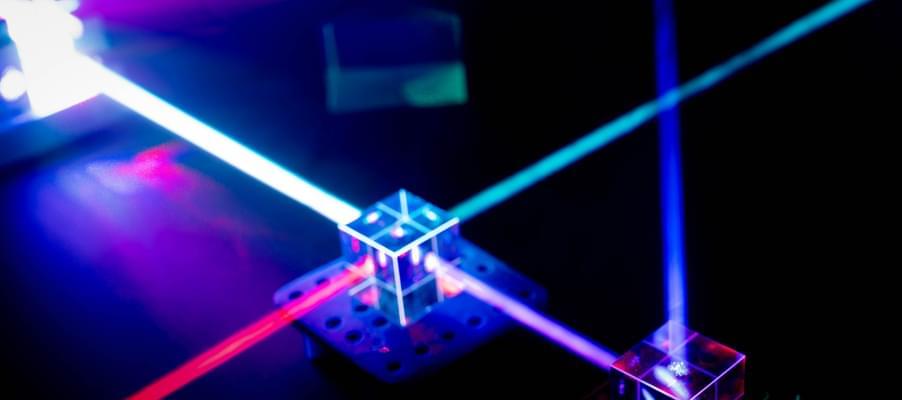

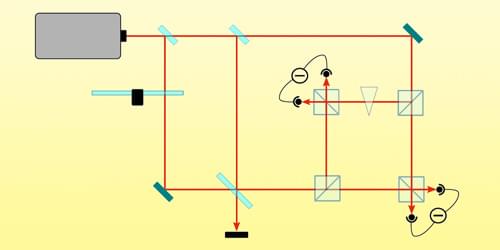

JILA and NIST Fellow James K. Thompson’s team of researchers have for the first time successfully combined two of the “spookiest” features of quantum mechanics to make a better quantum sensor: entanglement between atoms and delocalization of atoms.

Einstein originally referred to entanglement as creating spooky action at a distance—the strange effect of quantum mechanics in which what happens to one atom somehow influences another atom somewhere else. Entanglement is at the heart of hoped-for quantum computers, quantum simulators and quantum sensors.

A second rather spooky aspect of quantum mechanics is delocalization, the fact that a single atom can be in more than one place at the same time. As described in their paper recently published in Nature, the Thompson group has combined the spookiness of both entanglement and delocalization to realize a matter-wave interferometer that can sense accelerations with a precision that surpasses the standard quantum limit (a limit on the accuracy of an experimental measurement at a quantum level) for the first time.

“We adapted an idea, developed for experiments to prove the existence of quantum gravity.”

According to Trinity College Dublin scientists, our brains could use quantum computation after applying an idea created to prove the existence of quantum gravity to investigate the human brain and its workings.

As stated, the correlation between the measured brain functions and conscious awareness and short-term memory function suggests that quantum processes are also a part of cognitive and conscious brain functioning.

Agsandrew/iStock.

Published in the Journal of Physics Communications on October 7, the study could provide information about consciousness, which is still a mystery for scientists.

Samsung will soon launch another Galaxy Quantum smartphone in its home country. While previous Galaxy Quantum series phones were based on Galaxy A series devices, Samsung has changed that trend this time.

The Galaxy Quantum 3 has been revealed in South Korea, and it’s coming soon to SK Telecom’s network. The smartphone will be available for pre-order from April 22 to April 25, 2022. The first 10,000 buyers of the phone will get a Google Play gift card. Neither Samsung nor SK Telecom has revealed the price tag of the upcoming device.

The smartphone is based on the Galaxy M53 5G, which was silently revealed in Europe a few days ago. The Galaxy Quantum 3 features a 6.7-inch Super AMOLED Infinity-O display with Full HD+ resolution and a 120Hz refresh rate. It features a 108MP primary rear camera, an 8MP ultrawide camera, a 2MP macro camera, a 2MP depth sensor, and a 32MP front-facing camera. It can record 4K 30fps videos using both front and rear cameras.

Scientists from Trinity College Dublin believe our brains could use quantum computation. Their discovery comes after they adapted an idea developed to prove the existence of quantum gravity to explore the human brain and its workings.

The brain functions measured were also correlated to short-term memory performance and conscious awareness, suggesting quantum processes are also part of cognitive and conscious brain functions.

If the team’s results can be confirmed—likely requiring advanced multidisciplinary approaches—they would enhance our general understanding of how the brain works and potentially how it can be maintained or even healed. They may also help find innovative technologies and build even more advanced quantum computers.