Quantum computers have the potential to vastly exceed the capabilities of conventional computers for certain tasks. But there is still a long way to go before they can help to solve real-world problems. Many applications require quantum processors with millions of quantum bits. Today’s prototypes merely come up with a few of these compute units.

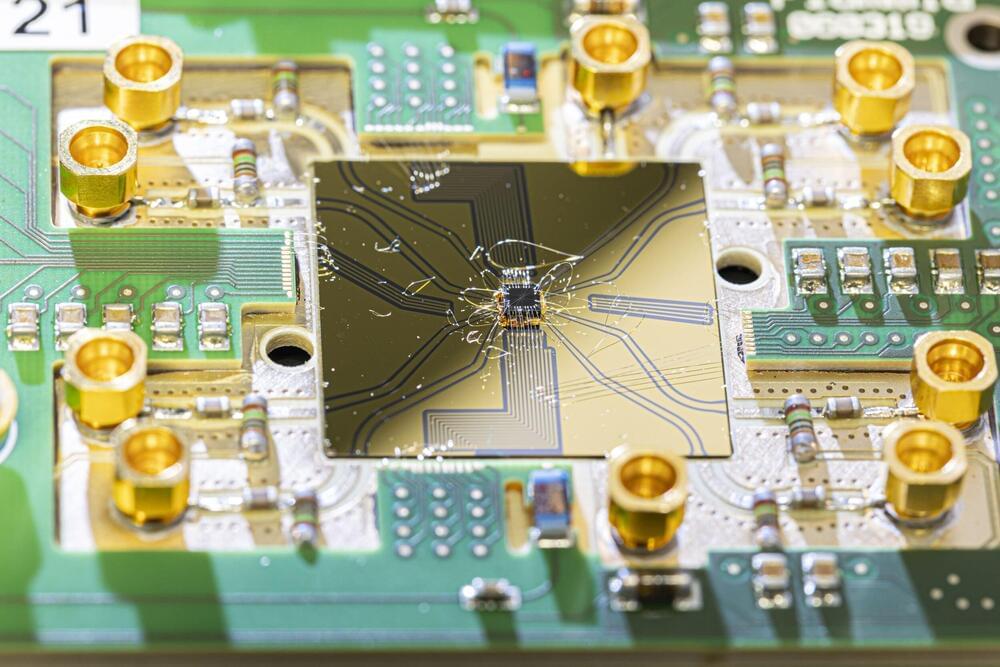

“Currently, each individual qubit is connected via several signal lines to control units about the size of a cupboard. That still works for a few qubits. But it no longer makes sense if you want to put millions of qubits on the chip. Because that’ s necessary for quantum error correction,” says Dr. Lars Schreiber from the JARA Institute for Quantum Information at Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University.

At some point, the number of signal lines becomes a bottleneck. The lines take up too much space compared to the size of the tiny qubits. And a quantum chip cannot have millions of inputs and outputs—a modern classical chip only contains about 2,000 of these. Together with colleagues at Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University, Schreiber has been conducting research for several years to find a solution to this problem.