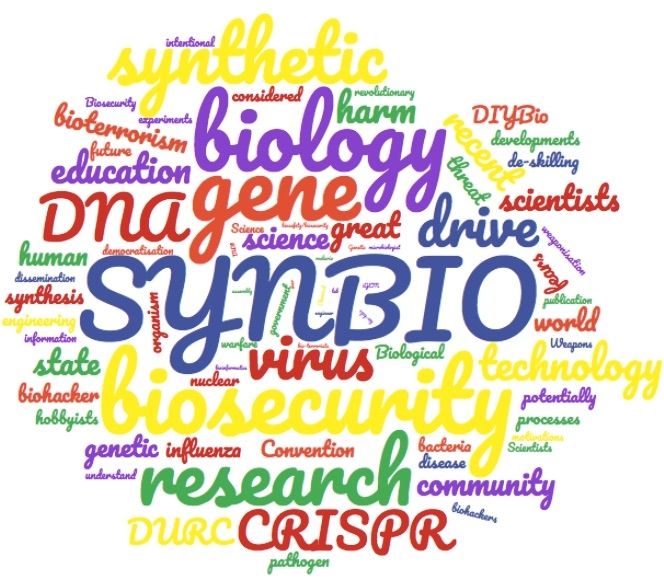

Wait until you see how Quantum bio is applied in Biosecurity.

By guest author Devang Mehta

The world in 1918 was emerging from under the pall of a World War that had claimed 38 million lives, and yet in the span of only one year, just as many lives would be lost to the Spanish Flu — an influenza pandemic that is still regarded the single deadliest epidemic in recorded history. The disease reached all corners of the world, from the Antipodes to Europe and Asia, eventually claiming 20–50 million lives. The 1918 virus caused unusually strong symptoms, described by one physician at the time as “a blood-tinged froth that sometimes gushed from (the) nose and mouth”. The disease also had an incredibly high mortality rate of 10–20%, which combined with a high rate of infection meant that up to 6% of the world’s population died due to the virus.

Ever since the outbreak, the particular H1N1 sub-strain that caused the pandemic has been a constant target of research by virologists seeking to understand the causes behind its lethality. In 2005 researchers in the US made a breakthrough where they isolated the virus’ genetic material from a frozen infected lung sample, deciphered its genetic sequence and then published it for anyone to see. Going a step further, the researchers resurrected the virus, using chemically synthesised DNA fragments, and showed that this very literal Frankenstein’s monster could kill mice at an enhanced rate compared to other extant flu viruses.

For perhaps obvious reasons this case has become standard in bioethics and especially synthetic biology lectures and discussions. The 1918 virus case was not the first successful attempt to ‘de-extinct’ a virus (that distinction goes to a 2002 study resurrecting the poliovirus), but this was one of the first studies to actually pass through regulatory processes (the approval of the newly formed U.S. National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity was obtained prior to publication); and of course influenza — a fast-spreading, potentially airborne virus — presents a more clear biosafety/biosecurity threat. Now, it is true that from a scientific point of view, these studies are very illuminating, and could possibly help stave off the effects of future pandemics. That logic guided the NSABB’s recommendation that the authors publish the full genetic sequence of the 1918 virus.