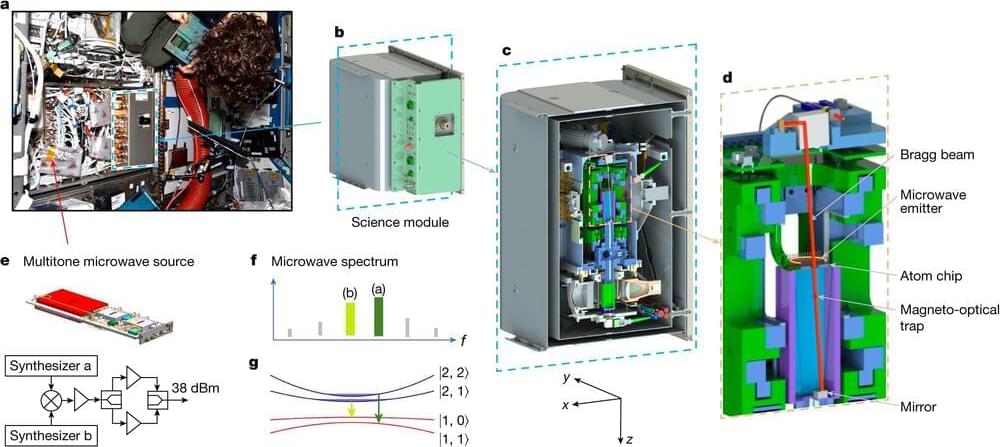

For the first time in space, scientists have produced a mixture of two quantum gases made of two types of atoms. Accomplished with NASA’s Cold Atom Laboratory aboard the International Space Station, the achievement marks another step toward bringing quantum technologies currently available only on Earth into space.

Physicists at Leibniz University Hannover (LUH), part of a collaboration led by Prof. Nicholas Bigelow, University of Rochester, provided the theoretical calculations necessary for this achievement. While quantum tools are already used in everything from cell phones to GPS to medical devices, in the future, quantum tools could be used to enhance the study of planets, including our own, as well as to help solve mysteries of the universe and deepen our understanding of the fundamental laws of nature.

The new work, performed remotely by scientists on Earth, is described in Nature.