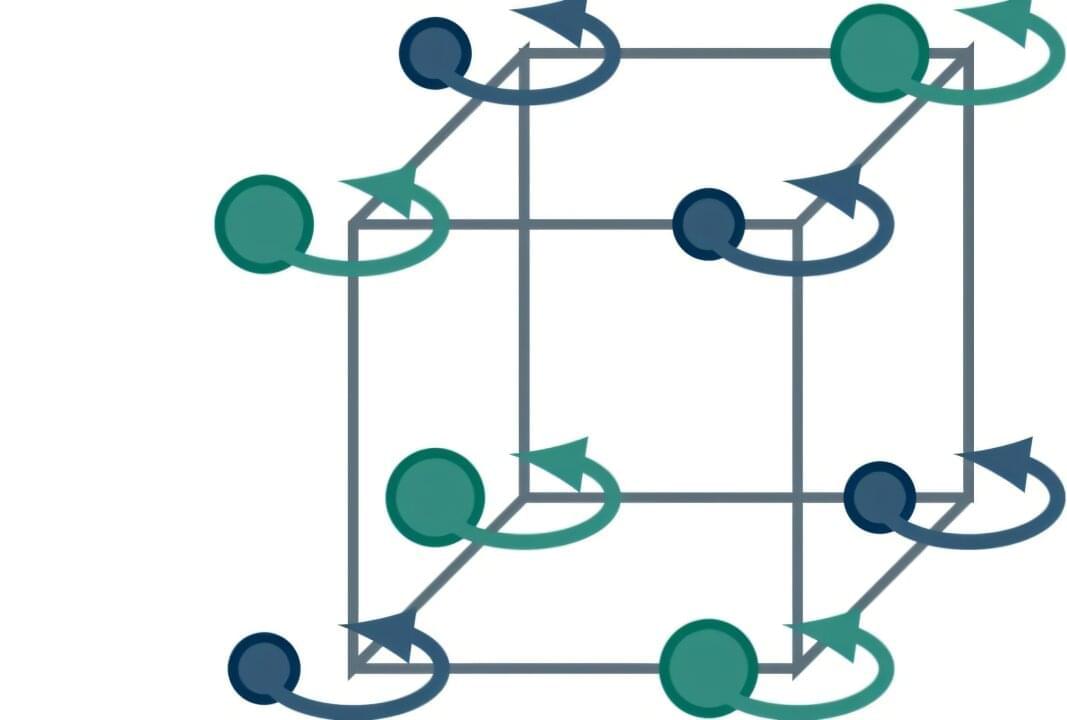

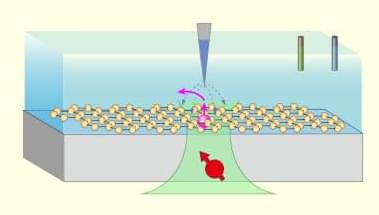

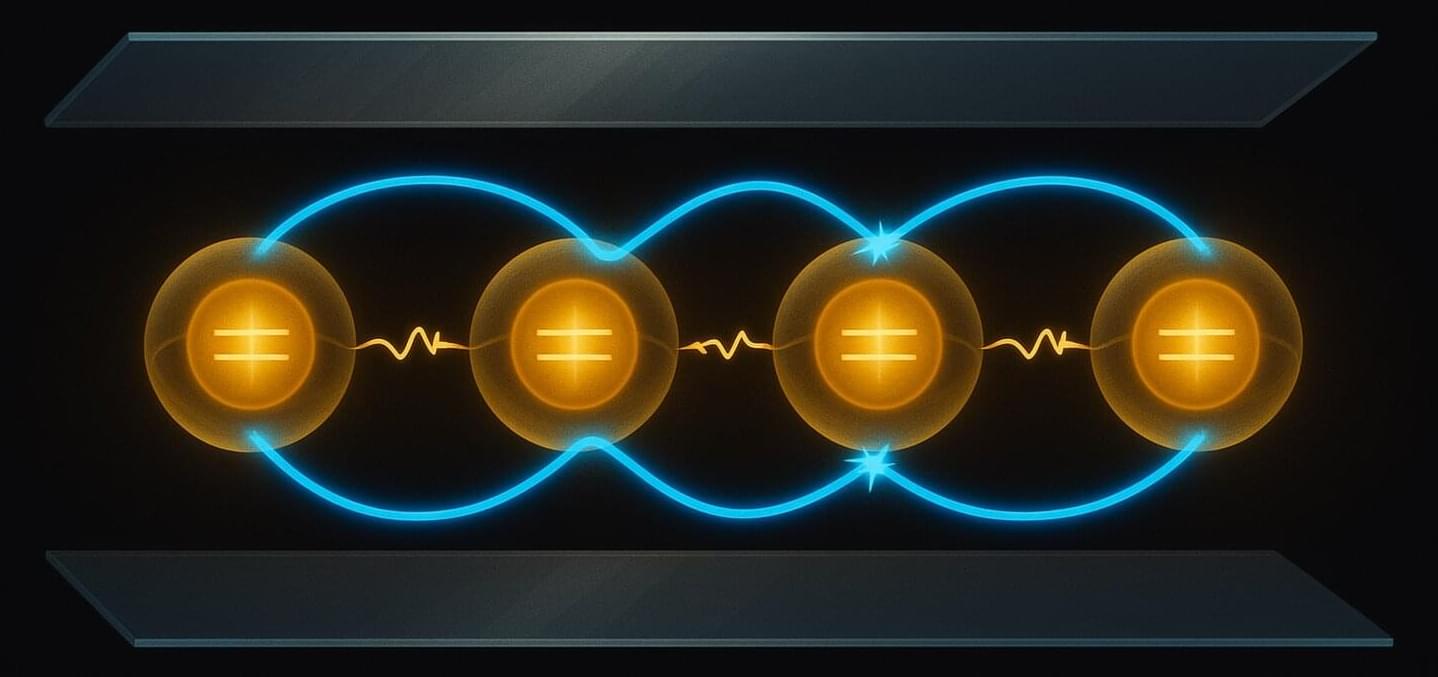

The rapidly growing field of research on chiral phonons is giving researchers new insights into the fundamental behaviors and structures of materials. The chirality of phonons could pave the way for new methods to control material properties and to encode information at the quantum level, which has implications for, among other areas, quantum technologies, electronics, energy transport, and sensor technology.

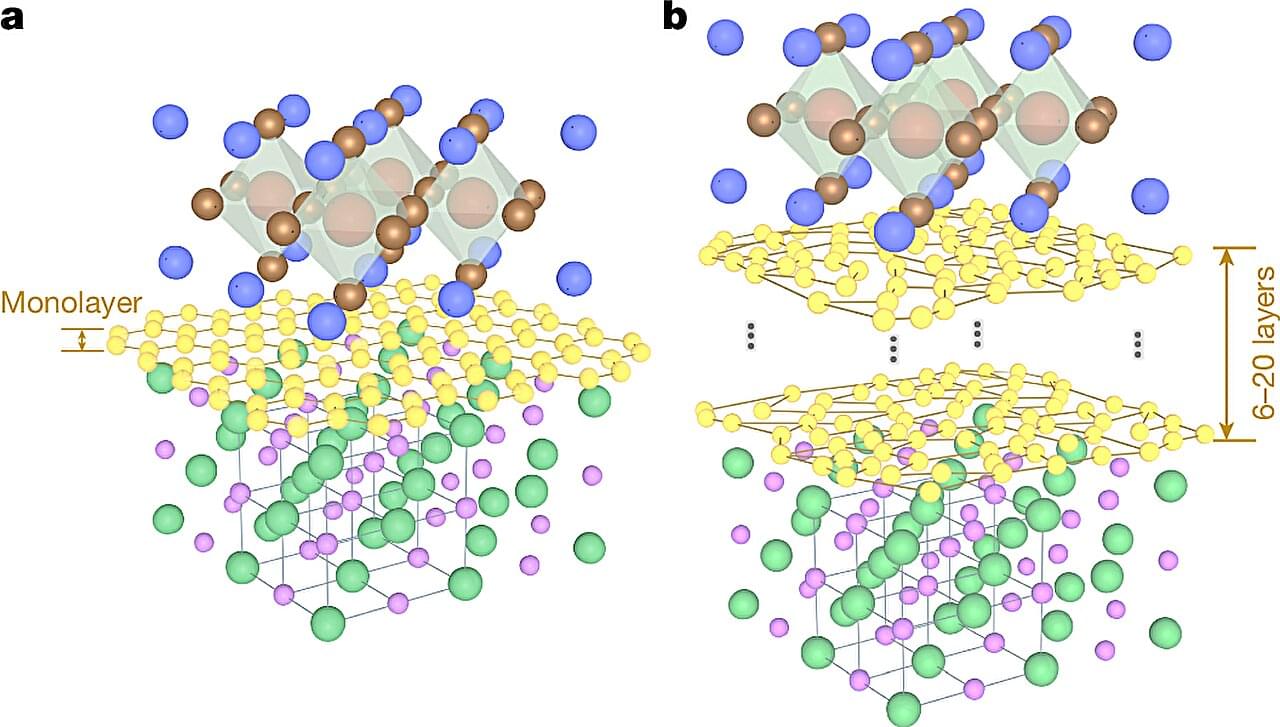

A recently published perpsective article in Nature Physics describes the development of this emerging research area, presents a framework for the classification of phonons, and provides a comprehensive overview of the materials in which chiral phonons have been studied or may be discovered in the future. This work is helping accelerate progress in one of today’s fastest-growing areas of quantum materials.

Matthias Geilhufe, Assistant Professor at the Department of Physics, conducts research on chiral phonons and is one of the main authors of the article.