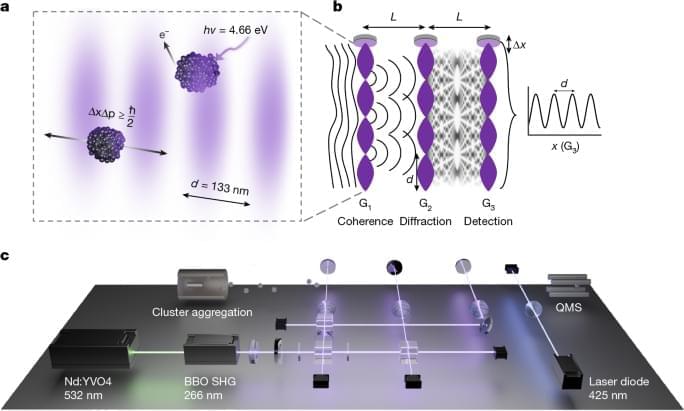

Quantum interference of sodium nanoparticles, which can each contain more than 7,000 atoms at masses greater than 170,000 Da, is demonstrated.

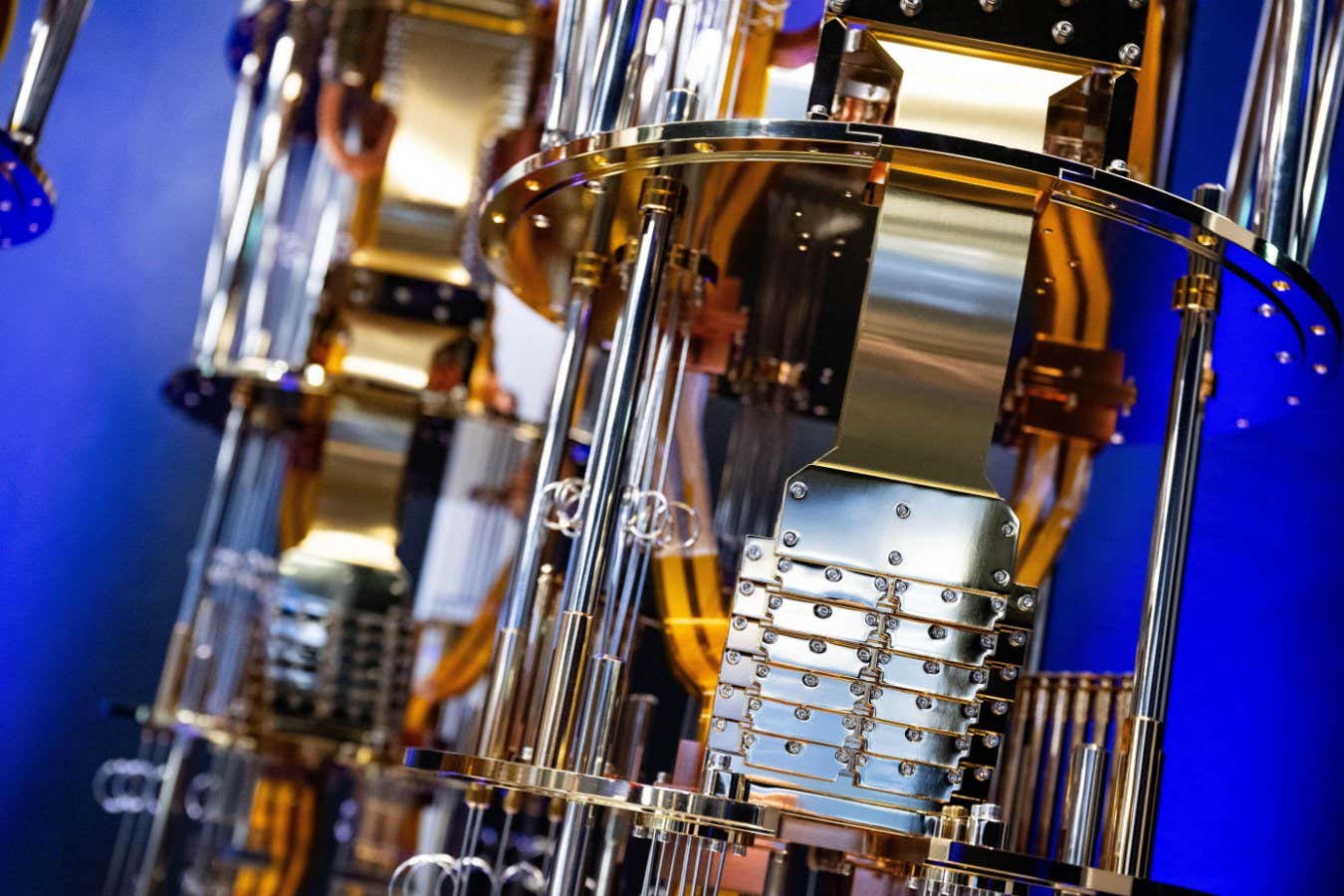

Quantum computers, systems that process information leveraging quantum mechanical effects, could reliably tackle various computational problems that cannot be solved by classical computers. These systems process information in the form of qubits, units of information that can exist in two states at once (0 and 1).

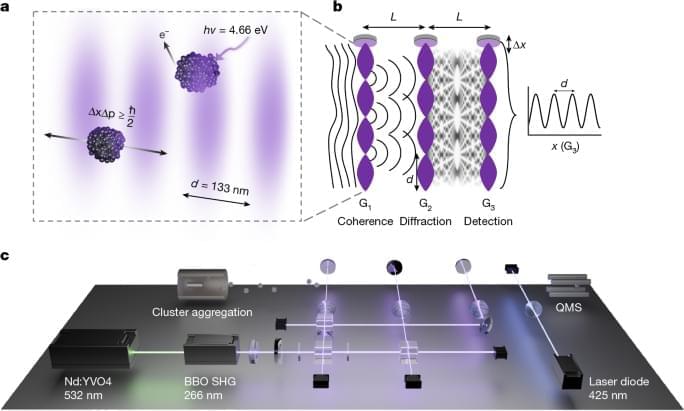

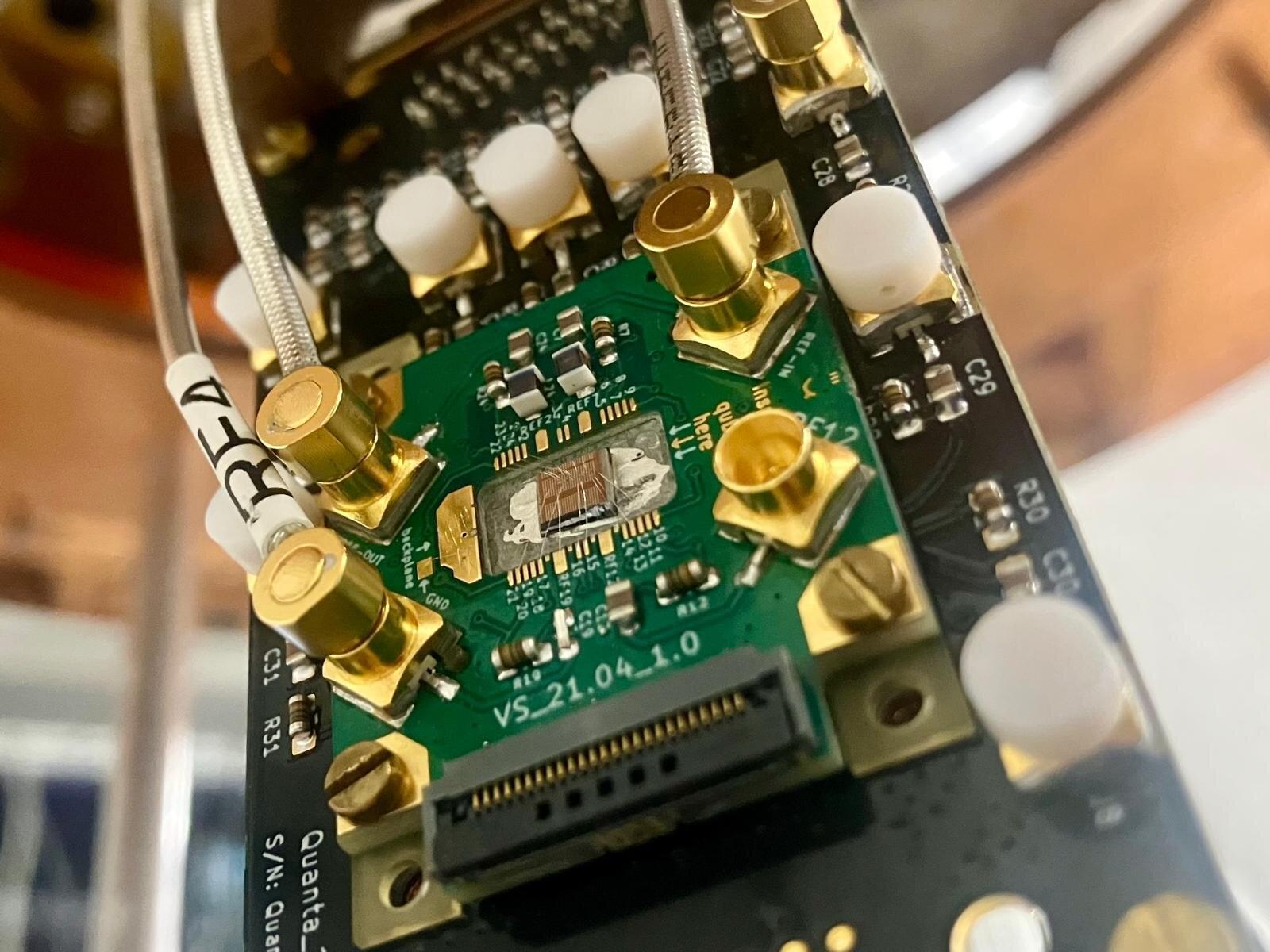

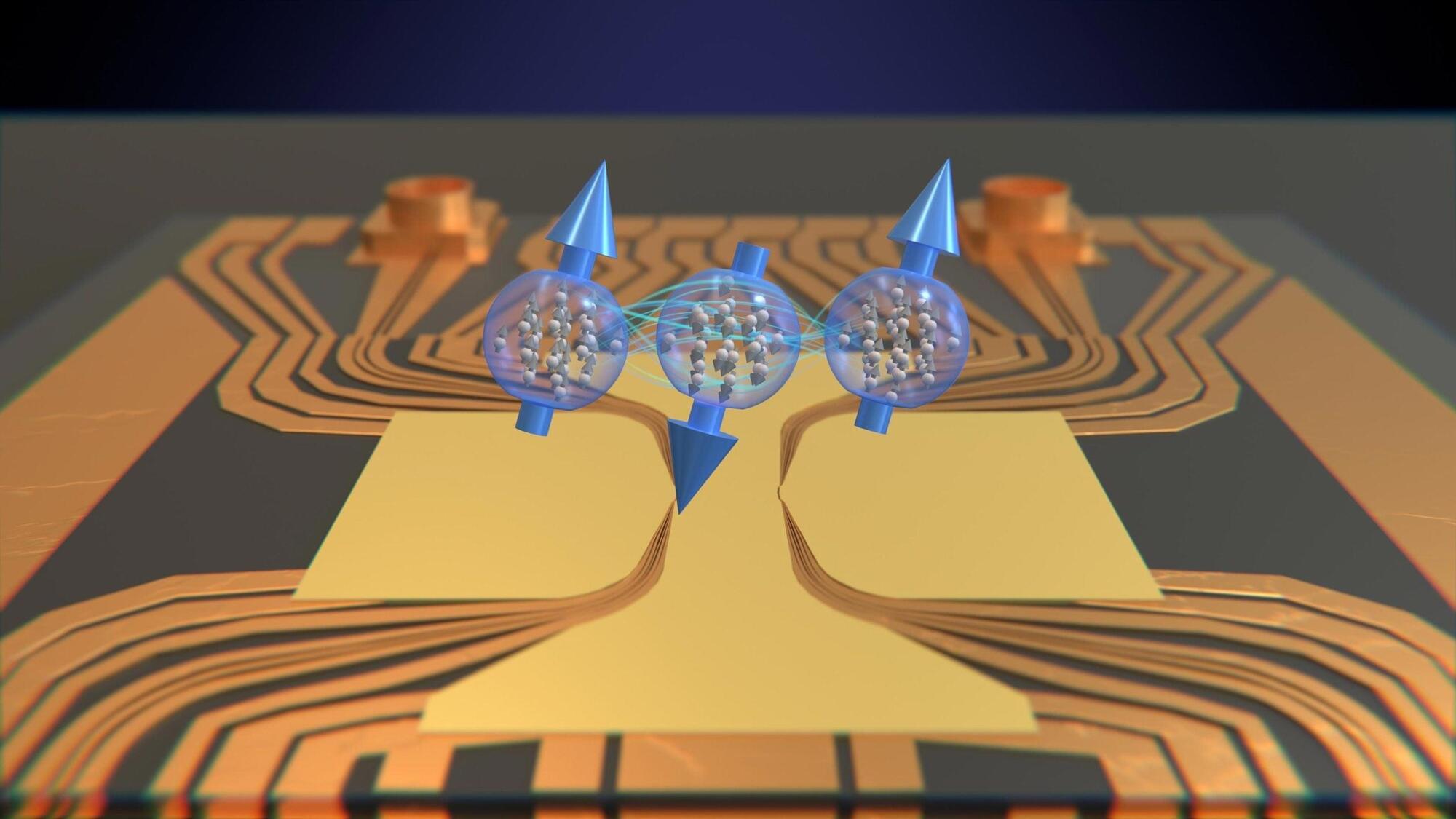

Hole spins, the intrinsic angular momentum of holes (i.e., missing electrons in semiconductors that can be trapped in nanoscale regions called quantum dots), have been widely used as qubits. These spins can be controlled using electric fields, as they are strongly influenced by a quantum effect known as spin-orbit coupling, which links the motion of particles to their magnetism.

Unfortunately, due to this spin-orbit coupling, hole spin qubits are also known to be highly vulnerable to noise, including random electrical disturbances that can prompt decoherence. This in turn can result in the loss of valuable quantum information.

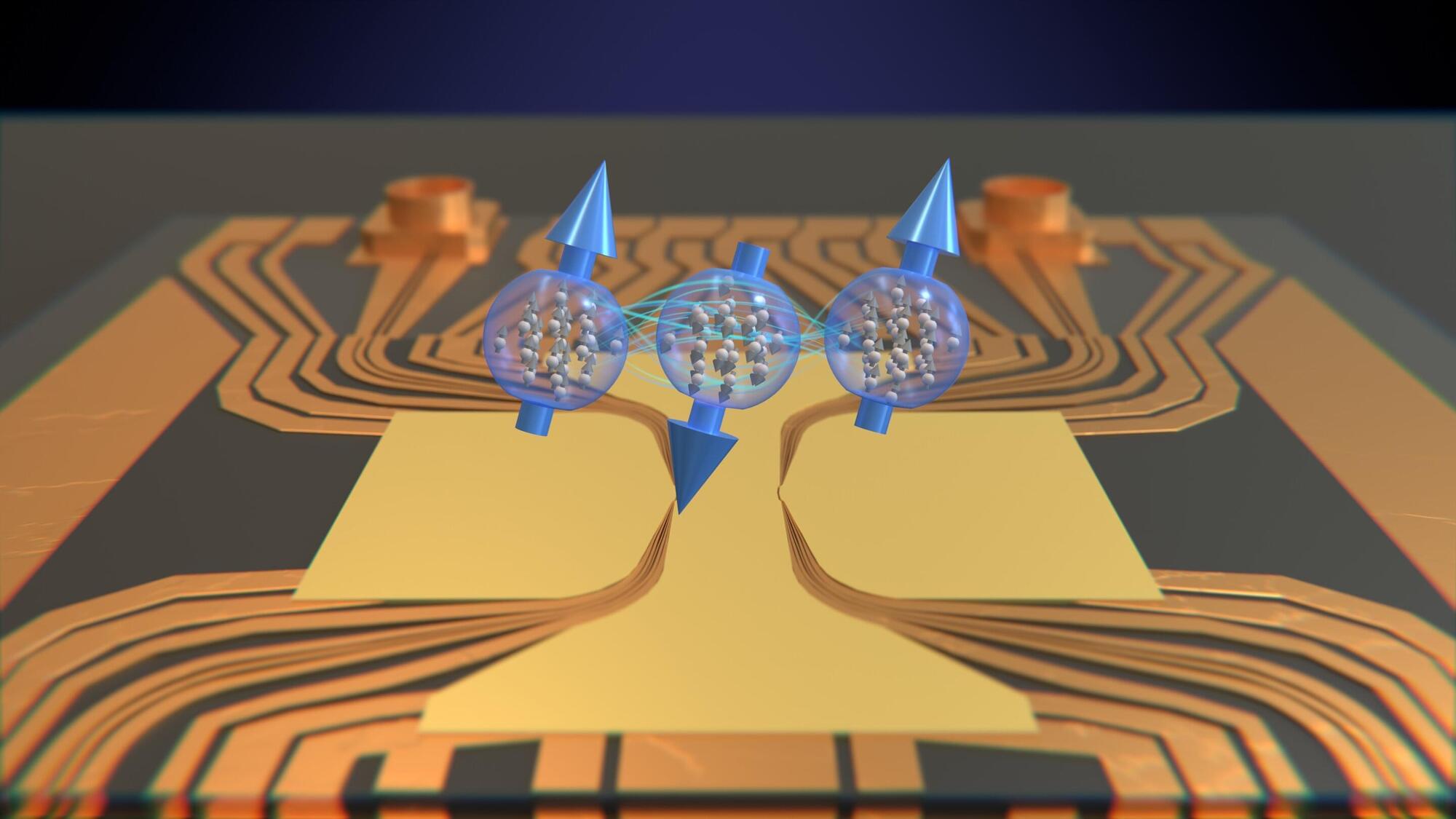

Researchers at the University of Basel and the Laboratoire Kastler Brossel have demonstrated how quantum mechanical entanglement can be used to measure several physical parameters simultaneously with greater precision.

Entanglement is probably the most puzzling phenomenon observed in quantum systems. It causes measurements on two quantum objects, even if they are at different locations, to exhibit statistical correlations that should not exist according to classical physics—it’s almost as if a measurement on one object influences the other one at a distance.

The experimental demonstration of this effect, also known as the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox, was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in physics.

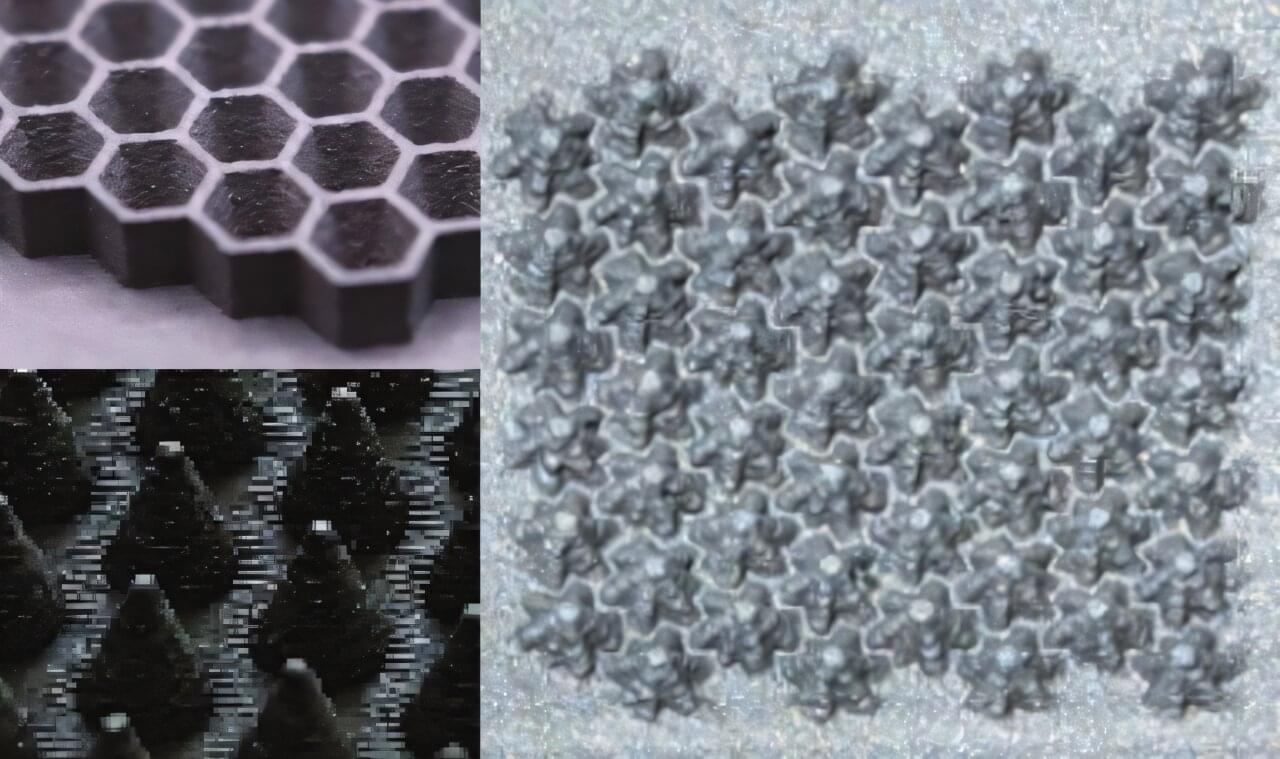

Scientists have created 3D printed surfaces featuring intricate textures that can be used to bounce unwanted gas particles away from quantum sensors, allowing useful particles like atoms to be delivered more efficiently, which could help improve measurement accuracy.

The researchers from the University of Nottingham’s School of Physics and Astronomy created intricate, fine-scale surface textures that preferentially bounce incident particles in particular directions. This can help to keep unwanted particles out of the way. The team demonstrated this by applying it to a surface-based vacuum pump and tripled the rate at which it removed nuisance gas particles.

The study, “Exploiting complex 3D-printed surface structures for portable quantum technologies,” is published in the journal Physical Review Applied.

Entangled atoms, separated in space, are giving scientists a powerful new way to measure the world with stunning precision.

Researchers from the University of Basel and the Laboratoire Kastler Brossel have shown that quantum entanglement can be used to measure multiple physical quantities at the same time with greater accuracy than previously possible.

What makes quantum entanglement so unusual.

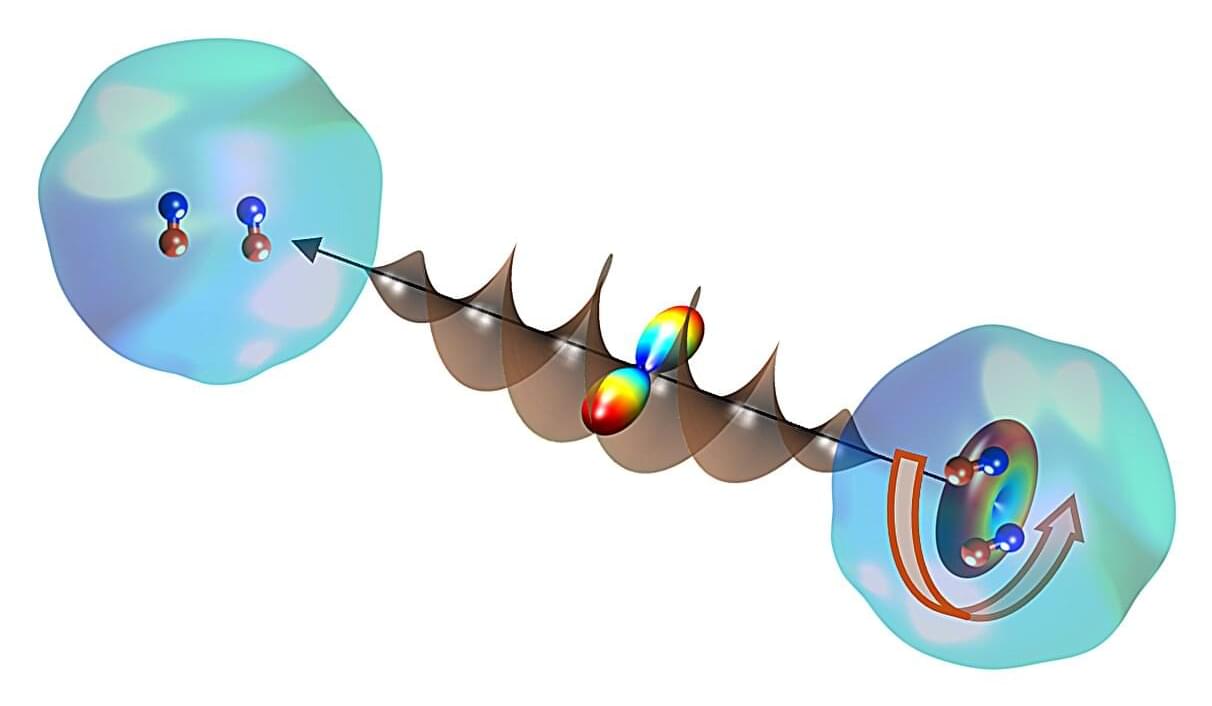

Physicists have used a new optical centrifuge to control the rotation of molecules suspended in liquid helium nano-droplets, bringing them a step closer to demystifying the behavior of exotic, frictionless superfluids.

It’s the first demonstration of controlled spinning inside a superfluid—researchers can now directly set the direction and frequency of the molecule’s rotation, which is vital in studying how molecules interact with the quantum environment at various rotational frequencies. The method was outlined this week by researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and colleagues at the University of Freiburg in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“Controlling the rotation of a molecule dissolved in any fluid is a challenge,” said Dr. Valery Milner, associate professor with UBC Physics and Astronomy and lead author on the paper.

Scientists are learning how to temporarily reshape materials by nudging their internal quantum rhythms instead of blasting them with extreme lasers. By harnessing excitons, short-lived energy pairs that naturally form inside semiconductors, researchers can alter how electrons behave using far less energy than before. This approach achieves powerful quantum effects without damaging the material, overcoming a major barrier that has limited progress for years.

A team of researchers led by the University of Warwick has developed the first unified framework for detecting “spacetime fluctuations”—tiny, random distortions in the fabric of spacetime that appear in many attempts to unite quantum physics and gravity.

These subtle fluctuations, first envisaged by physicist John Wheeler, are thought to arise naturally in several leading theories of quantum gravity. But because different models of gravity predict different forms of these fluctuations, experimental teams have until now lacked clear guidance on what to look for.