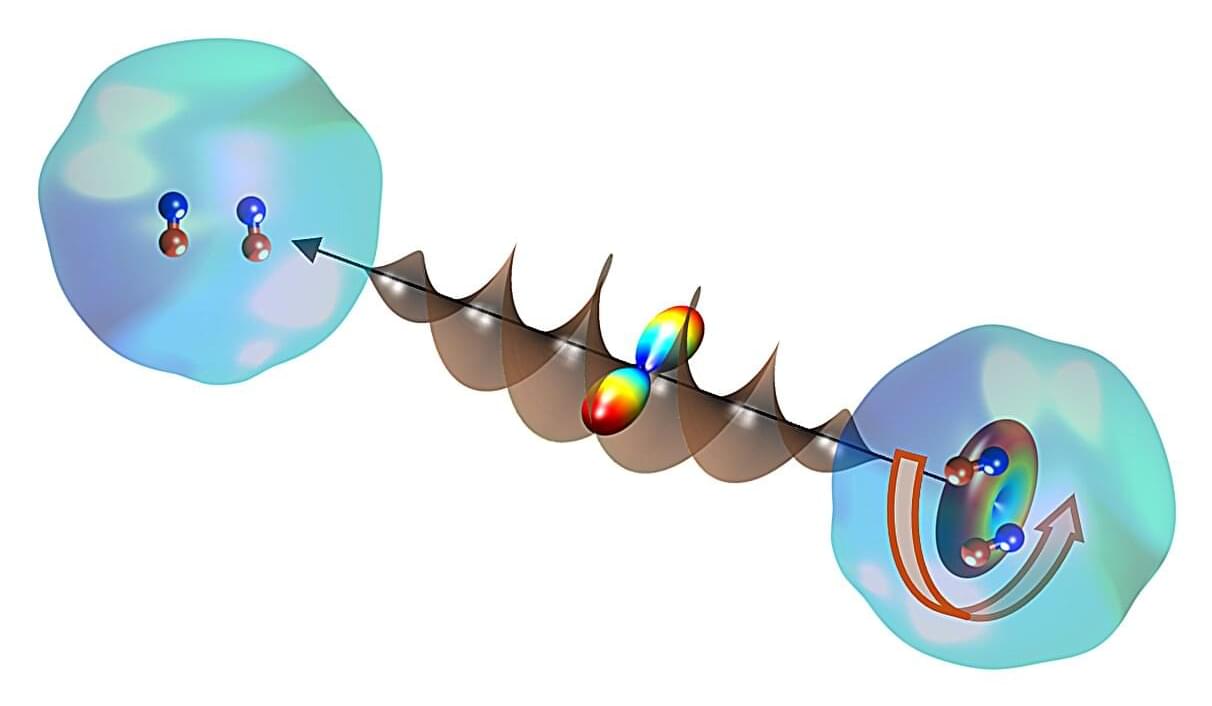

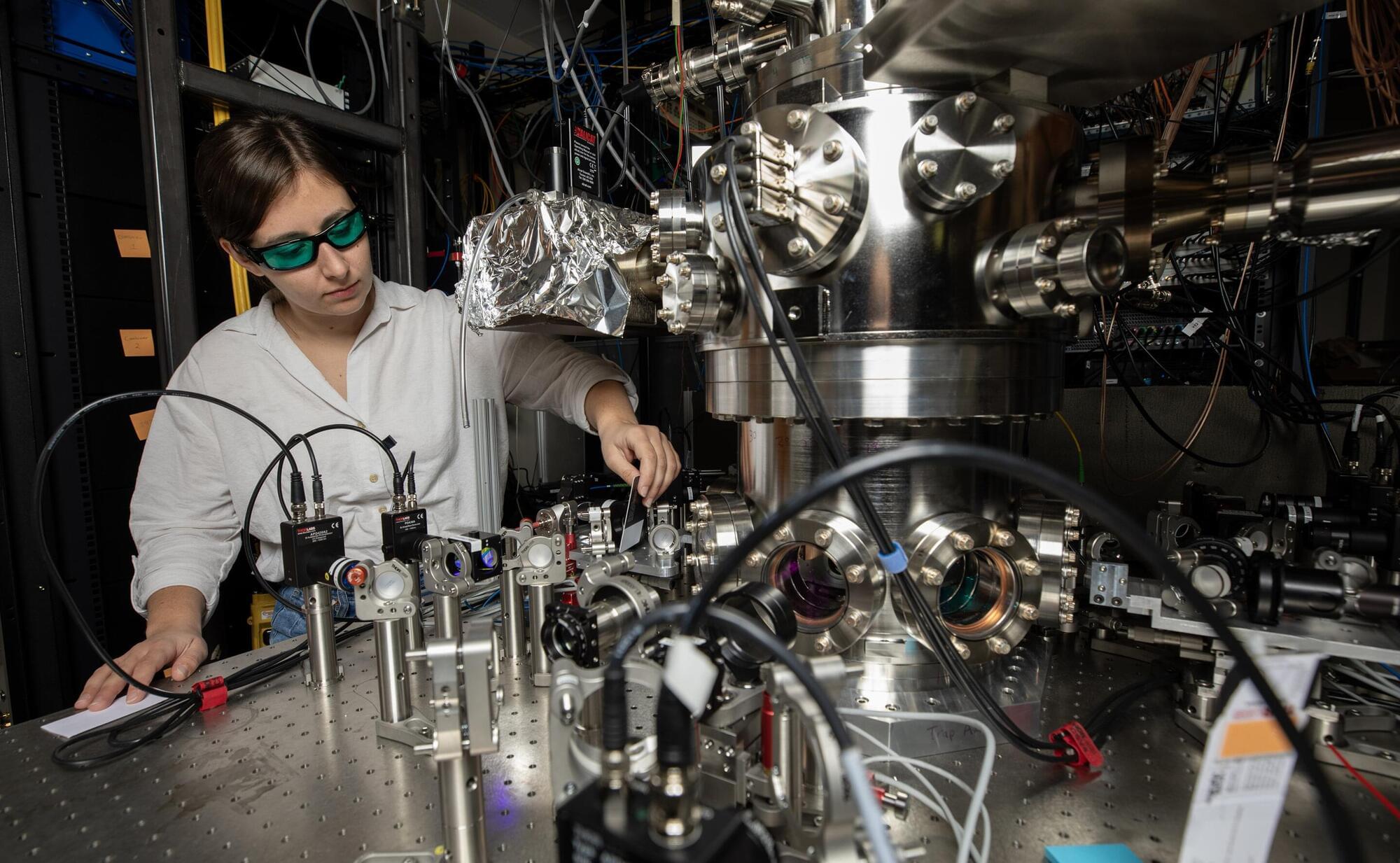

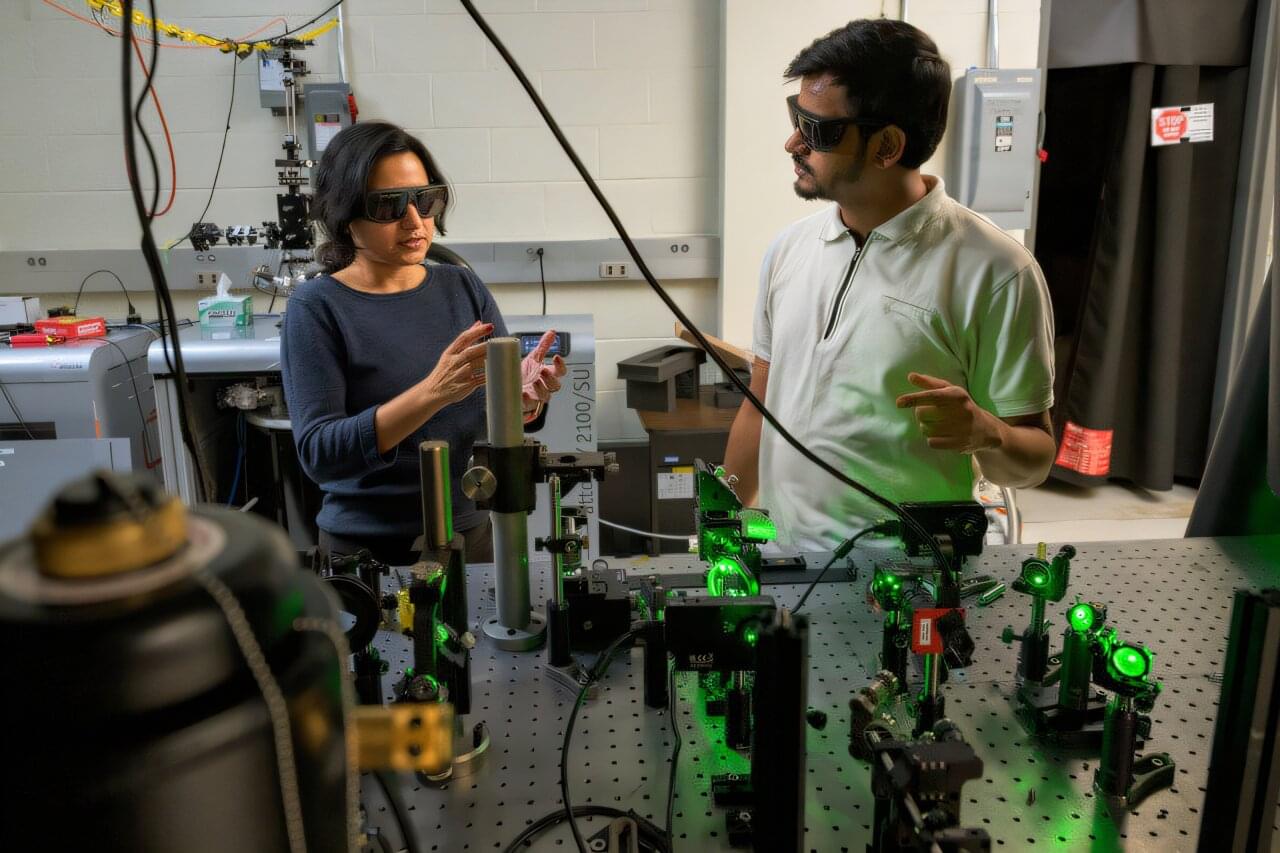

Physicists have used a new optical centrifuge to control the rotation of molecules suspended in liquid helium nano-droplets, bringing them a step closer to demystifying the behavior of exotic, frictionless superfluids.

It’s the first demonstration of controlled spinning inside a superfluid—researchers can now directly set the direction and frequency of the molecule’s rotation, which is vital in studying how molecules interact with the quantum environment at various rotational frequencies. The method was outlined this week by researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and colleagues at the University of Freiburg in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“Controlling the rotation of a molecule dissolved in any fluid is a challenge,” said Dr. Valery Milner, associate professor with UBC Physics and Astronomy and lead author on the paper.