Recent findings from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument suggest the possibility of new physics that extends beyond the current standard model of cosmology. Using the lab’s new Aurora exascale computing system, the research team conducted high-resolution simulations of the universe’s evoluti

Category: quantum physics – Page 163

The Rise of Self-Improving AI Agents: Will It Surpass OpenAI?

What happens when AI starts improving itself without human input? Self-improving AI agents are evolving faster than anyone predicted—rewriting their own code, learning from mistakes, and inching closer to surpassing giants like OpenAI. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the AI singularity’s opening act, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

How do self-improving agents work? Unlike static models such as GPT-4, these systems use recursive self-improvement—analyzing their flaws, generating smarter algorithms, and iterating endlessly. Projects like AutoGPT and BabyAGI already demonstrate eerie autonomy, from debugging code to launching micro-businesses. We’ll dissect their architecture and compare them to OpenAI’s human-dependent models. Spoiler: The gap is narrowing fast.

Why is OpenAI sweating? While OpenAI focuses on safety and scalability, self-improving agents prioritize raw, exponential growth. Imagine an AI that optimizes itself 24/7, mastering quantum computing over a weekend or cracking protein folding in hours. But there’s a dark side: no “off switch,” biased self-modifications, and the risk of uncontrolled superintelligence.

Who will dominate the AI race? We’ll explore leaked research, ethical debates, and the critical question: Can OpenAI’s cautious approach outpace agents that learn to outthink their creators? Like, subscribe, and hit the bell—the future of AI is rewriting itself.

Can self-improving AI surpass OpenAI? What are autonomous AI agents? How dangerous is recursive AI? Will AI become uncontrollable? Can we stop self-improving AI? This video exposes the truth. Watch now—before the machines outpace us.

#ai.

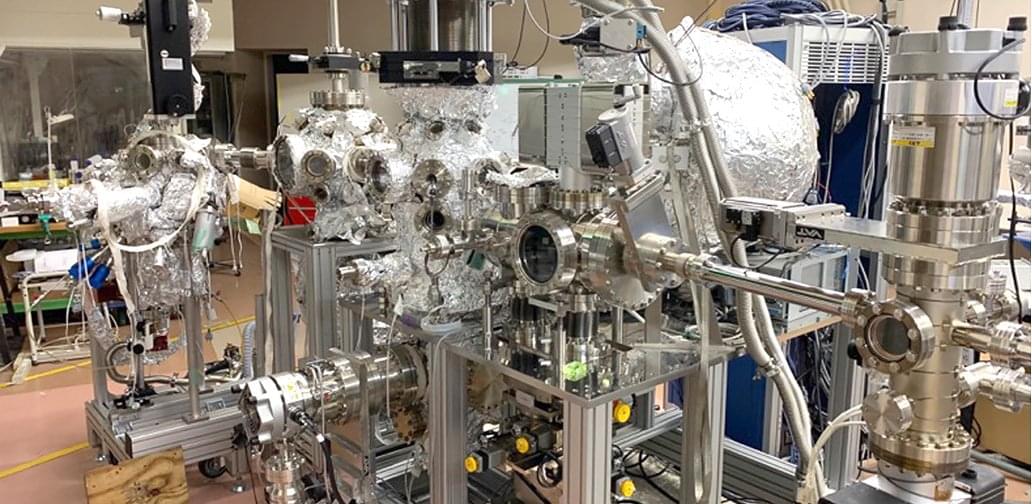

Turning Non-Magnetic Materials Magnetic with Atomically Thin Films

The rules about magnetic order may need to be rewritten. Researchers have discovered that chromium selenide (Cr₂Se₃) — traditionally non-magnetic in bulk form — transforms into a magnetic material when reduced to atomically thin layers. This finding contradicts previous theoretical predictions, and opens new possibilities for spintronics applications. This could lead to faster, smaller, and more efficient electronic components for smartphones, data storage, and other essential technologies.

An international research team from Tohoku University, Université de Lorraine (Synchrotron SOLEIL), the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), High Energy Accelerator Research Organization, and National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology successfully grew two-dimensional Cr₂Se₃ thin films on graphene using molecular beam epitaxy. By systematically reducing the thickness from three layers to one layer and analyzing them with high-brightness synchrotron X-rays, the team made a surprising discovery. This finding challenges conventional theoretical predictions that two-dimensional materials cannot maintain magnetic order.

“When we first observed the ferromagnetic behavior in these ultra-thin films, we were genuinely shocked,” explains Professor Takafumi Sato (WPI-AIMR, Tohoku University), the lead researcher. “Conventional theory told us this shouldn’t happen. What’s even more fascinating is that the thinner we made the films, the stronger the magnetic properties became—completely contrary to what we expected.”

Adi Newton — Intercepted Quantum Entanglement Transmission

What if with the condition machine super intelligence is possible once one comes into existence it sends von Neumann machines that converts solar systems into computers of like power and intelligence such machines would be factories miles long and they as well would be do the same until the entire galaxy would become an artificially intelligent entity procreating matrioska brains.

Adi Newton’s track from the compilation “The Neuromancers. Music inspired by William Gibson’s universe” published by Unexplained Sounds Group: https://unexplainedsoundsgroup.bandca… dl, cd, book. Music by: Adi Newton, NYORAI, Oubys (Wannes Kolf), Mario Lino Stancati, Joel Gilardini, Tescon Pol, phoanøgramma, Dead Voices On Air, SIGILLUM S, Richard Bégin, André Uhl. Stories by: Stories by: Andrew Coulthard, Chris McAuley, Glynn Owen Barrass, J. Edwin Buja, Michael F. Housel, Paolo L. Bandera, Rusell Smeaton, Scott J. Couturier. The soundtrack of a future in flux As the father of cyberpunk, William Gibson imagined a world where technology and society collide, blurring the boundaries between human and machine, individual and system. His novels, particularly Neuromancer, painted a dystopian future where sprawling megacities pulse with neon, corporations rule from the shadows, and cyberspace serves as both playground and battlefield. In his vision, technology is a tool of empowerment and control, a paradox that resonates deeply in our contemporary world. Gibson’s work has long since transcended literature, becoming a blueprint for how we understand technology’s role in shaping our lives. The term cyberspace, which he coined, feels more real than ever in today’s internet-driven world. We live in a time where virtual spaces are as important as physical ones, where our identities shift between digital avatars and flesh-and-blood selves. The rapid rise of AI, neural interfaces, and virtual reality feels like a prophecy fulfilled — as though we’ve stepped into the pages of a Gibson novel. A SONIC LANDSCAPE OF THE FUTURE The influence of cyberpunk on contemporary music is undeniable. The genre’s aesthetic, with its dark, neon-lit streets and synth-driven soundscapes, has found its way into countless genres, from techno and industrial to synthwave and ambient. Electronic music, in particular, feels like the natural soundtrack of the cyberpunk world — synthetic, futuristic, and often eerie, it evokes the idea of a humanity at the edge of a technological abyss. The cyberpunk universe forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about the way we live today: the increasing corporatization of our world, the erosion of privacy, and the creeping sense that technology is evolving faster than we can control. Though cyberpunk as a literary genre originated in the 1980s, its influence has only grown in the decades since. In music, the cyberpunk ethos is more relevant than ever. Artists today are embracing the tools of technology not just to create new sounds, but to challenge the very definition of music itself. THE FUTURE OF MUSIC IN A CYBERPUNK WORLD Much like Gibson’s writing, the music in this compilation embraces technology not only as a tool but as a medium of expression. It’s no coincidence that many of the artists featured here draw from electronic, industrial, and experimental music scenes—genres that have consistently pushed the boundaries of sound and technology. The contributions of Adi Newton, a pioneering figure in cyberpunk music, along with artists such as Dead Voices On Air, Sigillum S, Tescon Pol, Oubys, Joel Gilardini, phoanøgramma, Richard Bégin, Mario Lino Stancati, Nyorai, Wahn, and André Uhl, each capture unique facets of the cyberpunk universe. Their work spans from the gritty, rebellious underworlds of hackers, to the cold, calculated precision of AI, and the vast, sprawling virtual landscapes where anything is possible—and everything is controlled. These tracks serve as a sonic exploration of Gibson’s vision, translating the technological, dystopian landscapes of his novels into sound. They are both a tribute and a challenge, asking us to reflect on what it means to be human in a world where technology has permeated every corner of our existence. Just as Gibson envisioned a future where humanity and machines converge, the artists in this compilation fuse organic and synthetic sounds, analog and digital techniques, to evoke the tensions of the world he foretold. Curated and mastered by Raffaele Pezzella (Sonologyst). Layout by Matteo Mariano. Cat. Num. USG105. Unexplained Sounds Network labels: https://unexplainedsoundsgroup.bandca… https://eighthtowerrecords.bandcamp.com https://sonologyst.bandcamp.com https://therecognitiontest.bandcamp.com https://zerok.bandcamp.com https://reversealignment.bandcamp.com Magazine and radio (Music, Fiction, Modern Mythologies) / eighthtower Please subscribe the channel to help us to create new music and videos. Great thanks to the patrons and followers for supporting and sustain the creative work we’re doing. Facebook:

/ unexplaineds… Instagram:

/ unexplained… Twitter:

/ sonologyst.

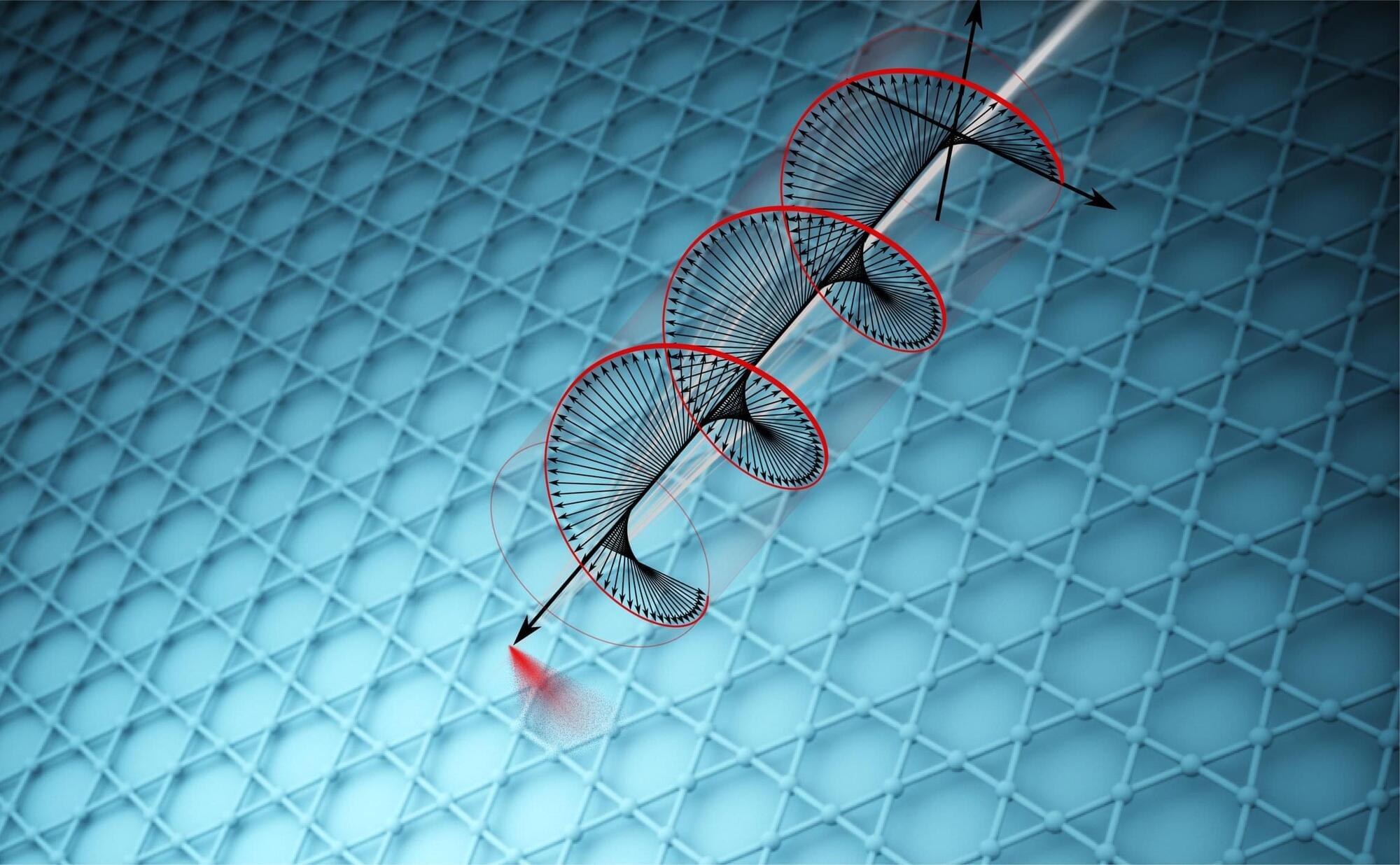

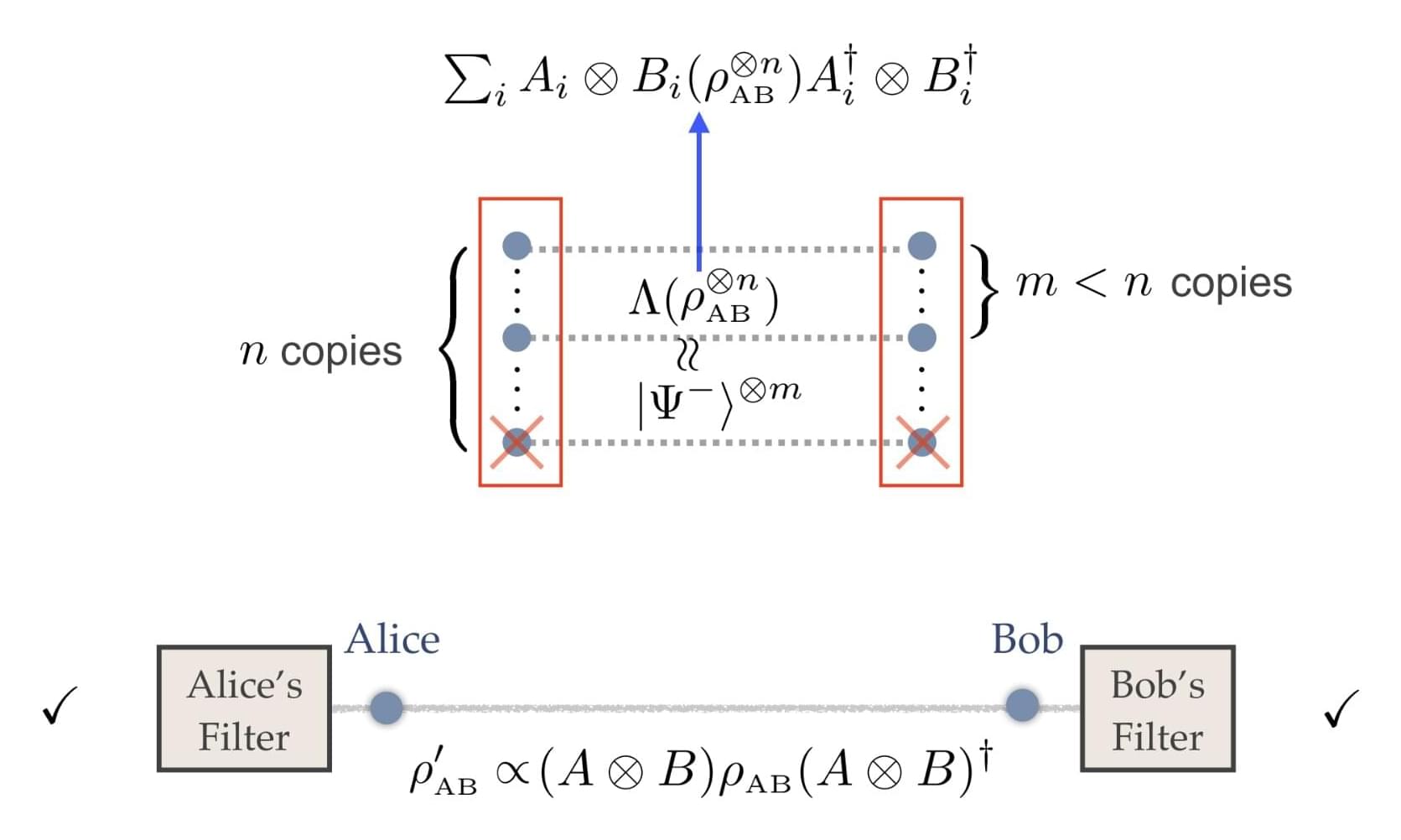

A scalable approach to distill quantum features from higher-dimensional entanglement

The operation of quantum technologies relies on the reliable realization and control of quantum states, particularly entanglement. In the context of quantum physics, entanglement entails a connection between particles, whereby measuring one determines the result of measuring the other even when they are distant from each other, and in a way that defies any intuitive explanation.

A key challenge in the development of reliable quantum technologies is that entanglement is highly susceptible to noise (i.e., random interactions with the environment). These interactions with noise can adversely impact this desired quantum state of affairs and, in turn, reduce the performance of quantum technologies.

Researchers at Shandong University in China and National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan recently implemented a key step to experimentally recover hidden quantum correlations from higher-dimensional entangled states.

Improved modeling of the Pockels effect may help advance optoelectronic technology

The use of light signals to connect electronic components is a key element of today’s data communication technologies, because of the speed and efficiency that only optical devices can guarantee. Photonic integrated circuits, which use photons instead of electrons to encode and transmit information, are found in many computing technologies. Most are currently based on silicon—a good solution because it is already used for electronic circuits, but with a limited bandwidth.

An excellent alternative is tetragonal barium titanate (BTO), a ferroelectric perovskite that can be grown on top of silicon and has much better optoelectronic properties. But since this material is quite new in the field of applied optoelectronics, a better comprehension of its quantum properties is needed in order to further optimize it.

A new study by MARVEL scientists published in Physical Review B presents a new computational framework to simulate the optoelectronic behavior of this material, and potentially of other promising ones.

Physicists Capture First-Ever Images of Free-Range Atoms

Free-range atoms, roaming around without restrictions, have been captured on camera for the first time – enabling physicists to take a closer look at long predicted quantum phenomena.

It’s a bit like snapping a shot of a rare bird in your back garden, after a long time of only ever hearing reports of them in the area, and seeing the food in your bird feeder diminish each day. Instead of birdwatching, though, we’re talking about quantum physics.

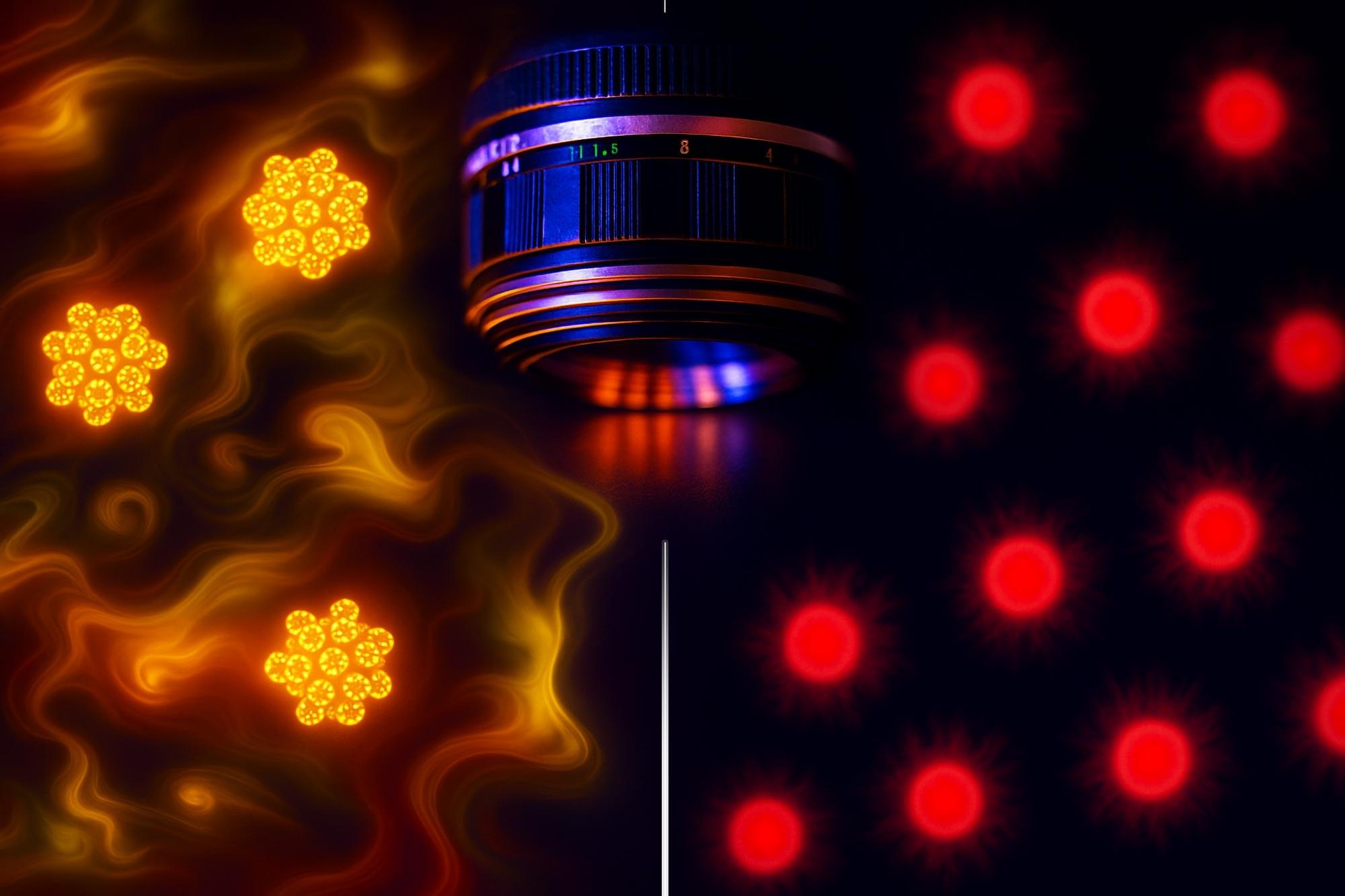

The US researchers behind the breakthrough carefully constructed an “atom-resolved microscopy” camera system that first puts atoms in a contained cloud, where they roam freely. Then, laser light freezes the atoms in position to record them.

“Faster Than Anything Ever Seen”: Mind-Blowing Speed of Quantum Entanglement Measured for the First Time in Scientific History

IN A NUTSHELL 🔬 Scientists have measured the speed of quantum entanglement for the first time, marking a major milestone in quantum physics. 💡 The study uses attosecond precision to track electron motion, offering unprecedented insight into quantum dynamics. 🔗 Quantum entanglement shows how particles can be interconnected over vast distances, defying traditional physics. 🚀