An innovative way to image atoms in cold gases could provide deeper insights into the atoms’ quantum correlations.

Two recent advances—one in nanoscale chemistry and another in astrophysics—are making waves. Scientists studying the movement of molecules in porous materials and researchers observing rare cosmic events have uncovered mechanisms that could reshape both industry and our view of the universe.

One of the most promising fields in material science centers on molecular diffusion. This is the way molecules move through small, confining spaces—a key process behind technologies like gas separation, catalysis, and energy storage. Materials called MOFs, short for metal-organic frameworks, have emerged as powerful tools because of their flexible structure and tunable chemistry.

Yet predicting how molecules behave inside these frameworks isn’t simple. Pore size, shape, chemical reactivity, and even how the material flexes all play a role. Studying these factors one by one has been manageable. But understanding how they work together to control molecular flow remains a major hurdle for material designers.

Growing evidence suggests that subatomic phenomena can shape fundamental activities in cells, including how organisms handle energy at the smallest scales. Quantum biology, as it’s being called, is no longer just a fringe idea among researchers.

On May 5, 2025, scientists at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem announced a study linking quantum mechanics with key cellular functions in protein-based systems.

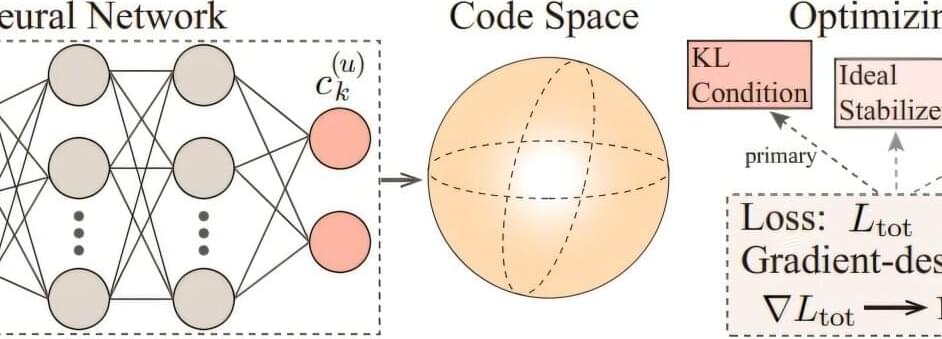

A way to greatly enhance the efficiency of a method for correcting errors in quantum computers has been realized by theoretical physicists at RIKEN. This advance could help to develop larger, more reliable quantum computers based on light.

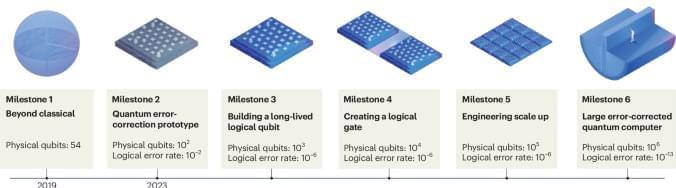

Quantum computers are looming large on the horizon, promising to revolutionize computing within the next decade or so.

“Quantum computers have the potential to solve problems beyond the capabilities of today’s most powerful supercomputers,” notes Franco Nori of the RIKEN Center for Quantum Computing (RQC).

In this profound and thought-provoking clip from the Quantum Convergence documentary, tech pioneer and physicist Federico Faggin delves into his transformative experience of consciousness — the moment he felt himself as the universe observing itself. Faggin, best known for his work in developing the first microprocessor, explores the fundamental nature of consciousness, its relationship with matter, and the deeper purpose of the universe.

🌐 About Quantum Convergence:

Quantum Convergence is a groundbreaking documentary that explores the intersection of science, technology, and consciousness. Featuring leading thinkers and visionaries, the film examines how our understanding of reality is evolving in the age of AI and quantum physics.

🔔 Subscribe for more transformative content:

📍 Stay updated with more clips and insights from Quantum Convergence by hitting the notification bell.

👍 Like, share, and comment if you believe in the power of consciousness.

#QuantumConvergence #Consciousness #FedericoFaggin #AI #Philosophy #Science #QuantumPhysics.

Learn more — https://www.infinitepotential.com/

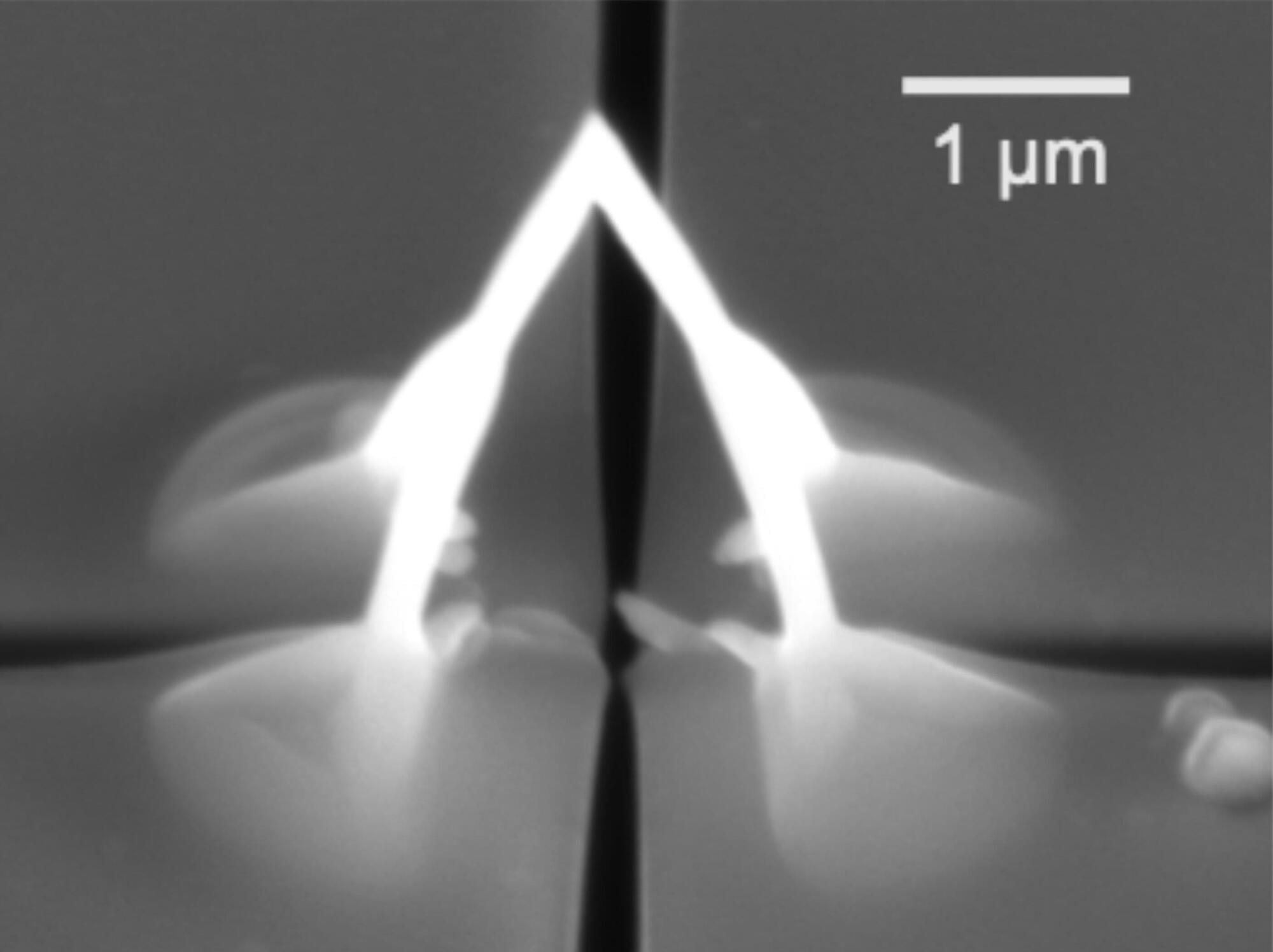

The move from two to three dimensions can have a significant impact on how a system behaves, whether it is folding a sheet of paper into a paper airplane or twisting a wire into a helical spring. At the nanoscale, 1,000 times smaller than a human hair, one approaches the fundamental length scales of, for example, quantum materials.

At these length scales, the patterning of nanogeometries can lead to changes in the material properties itself—and when one moves to three dimensions, there come new ways to tailor functionalities, by breaking symmetries, introducing curvature, and creating interconnected channels.

Despite these exciting prospects, one of the main challenges remains: how to realize such complex 3D geometries, at the nanoscale, in quantum materials? In a new study, an international team led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids have created three-dimensional superconducting nanostructures using a technique similar to a nano-3D printer.

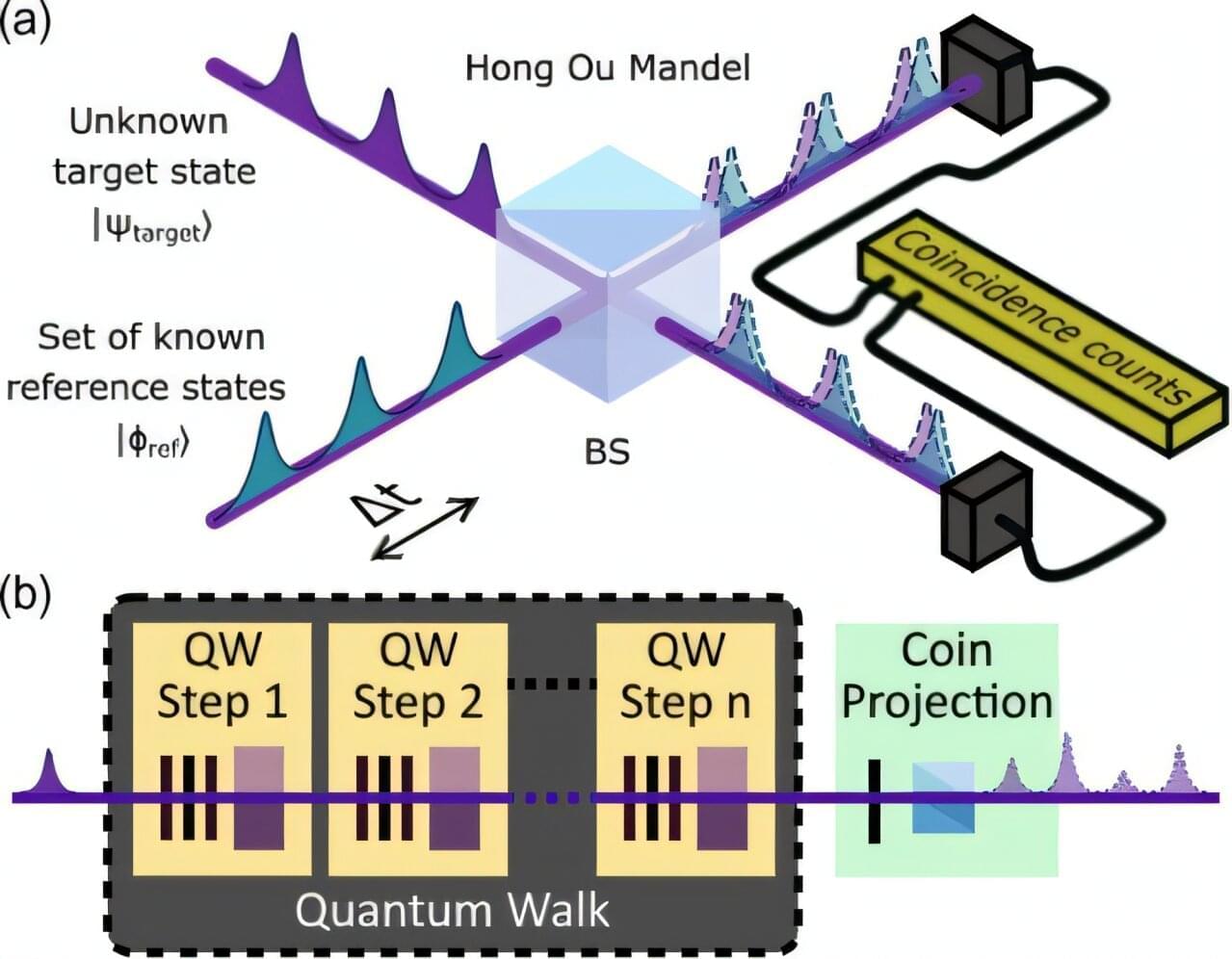

A team of researchers has developed a technique that makes high-dimensional quantum information encoded in light more practical and reliable.

This advancement, published in Physical Review Letters, could pave the way for more secure data transmission and next-generation quantum technologies.

Quantum information can be stored in the precise timing of single photons, which are tiny particles of light.