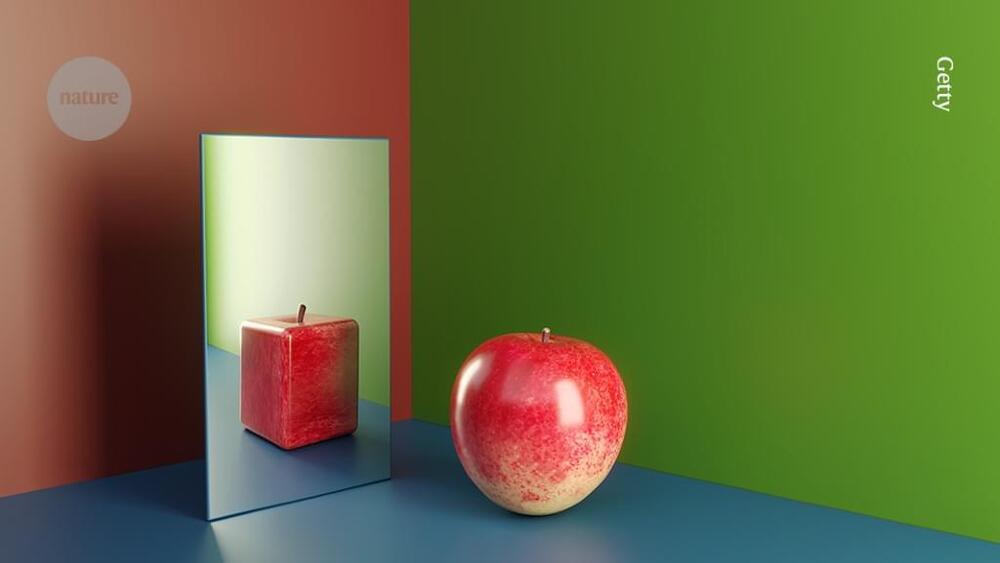

Princeton physicists have uncovered a groundbreaking quantum phase transition in superconductivity, challenging established theories and highlighting the need for new approaches to understanding quantum mechanics in solids.

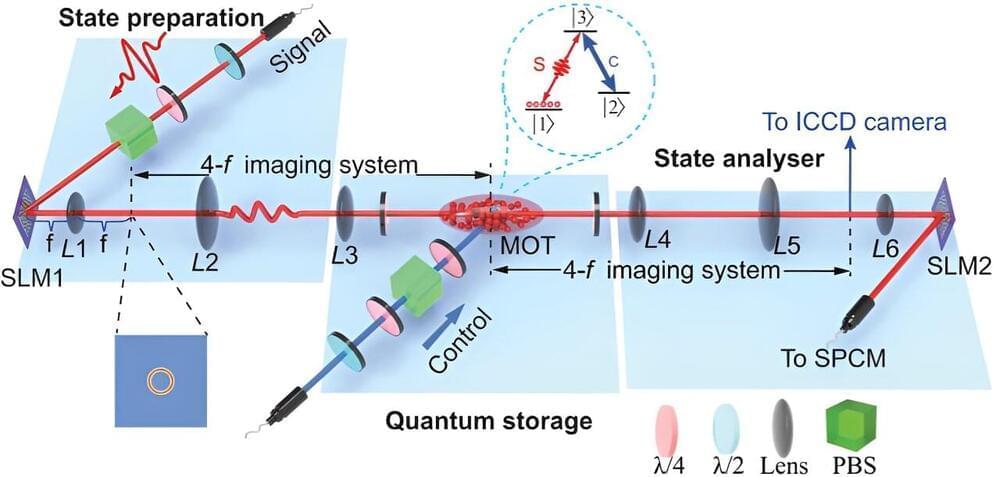

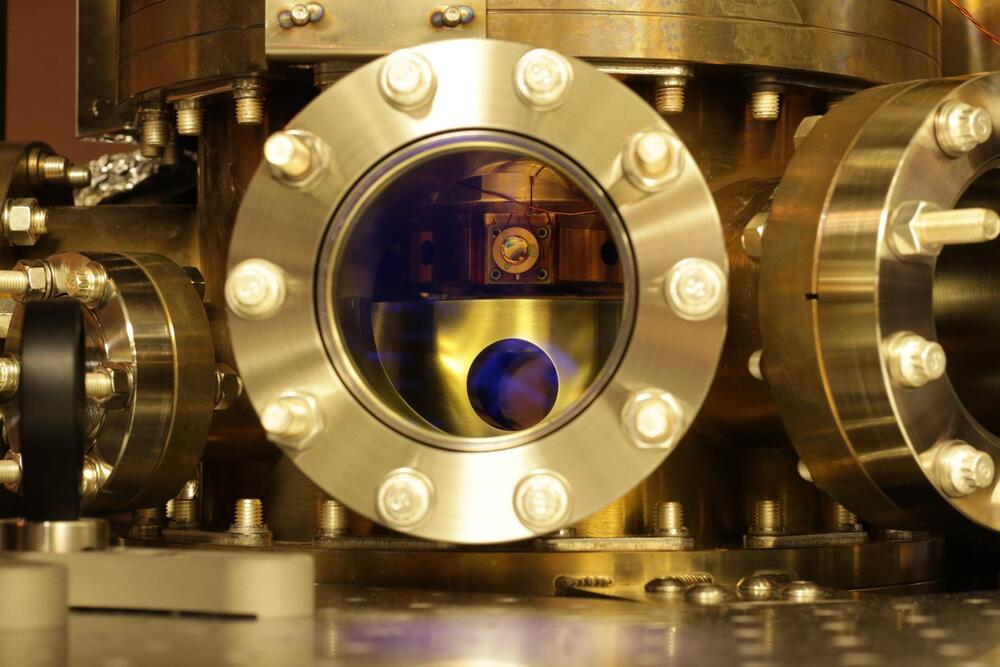

Princeton physicists have discovered an abrupt change in quantum behavior while experimenting with a three-atom.

An atom is the smallest component of an element. It is made up of protons and neutrons within the nucleus, and electrons circling the nucleus.