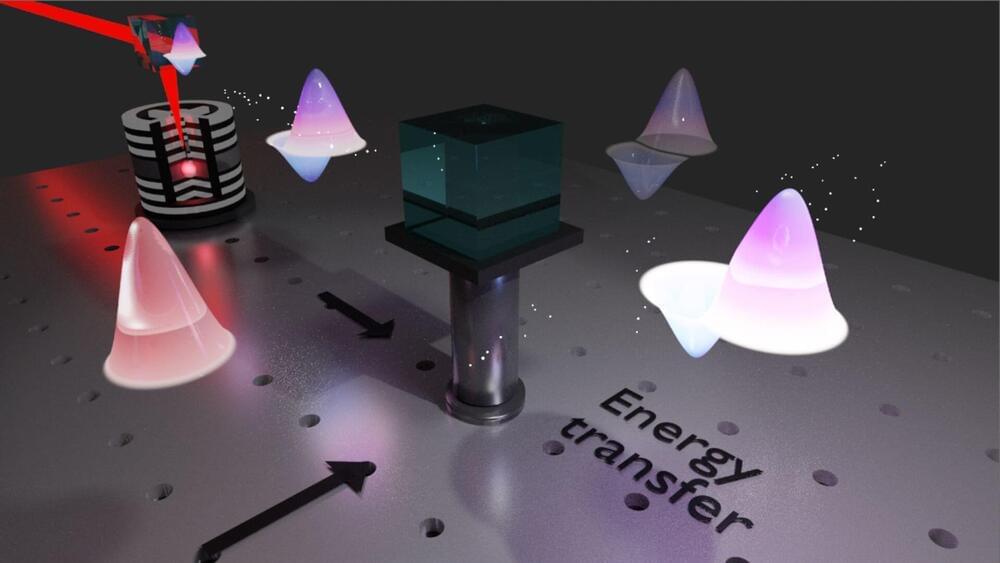

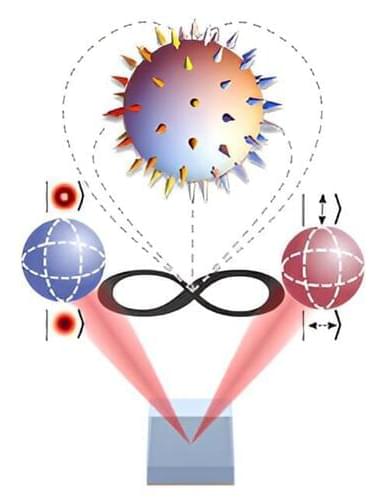

Scientists uncover new insights on polaritons, showing potential for breakthroughs in light manipulation and nanotechnology applications.

An international team of scientists provides an overview of the latest research on light-matter interactions. A team of scientists from the Fritz Haber Institute, the City University of New York, and the Universidad de Oviedo has published a comprehensive review article in the scientific journal Nature Reviews Materials. In this article, they provide an overview of the latest research on polaritons, tiny particles that arise when light and material interact in a special way.

Understanding Polaritons