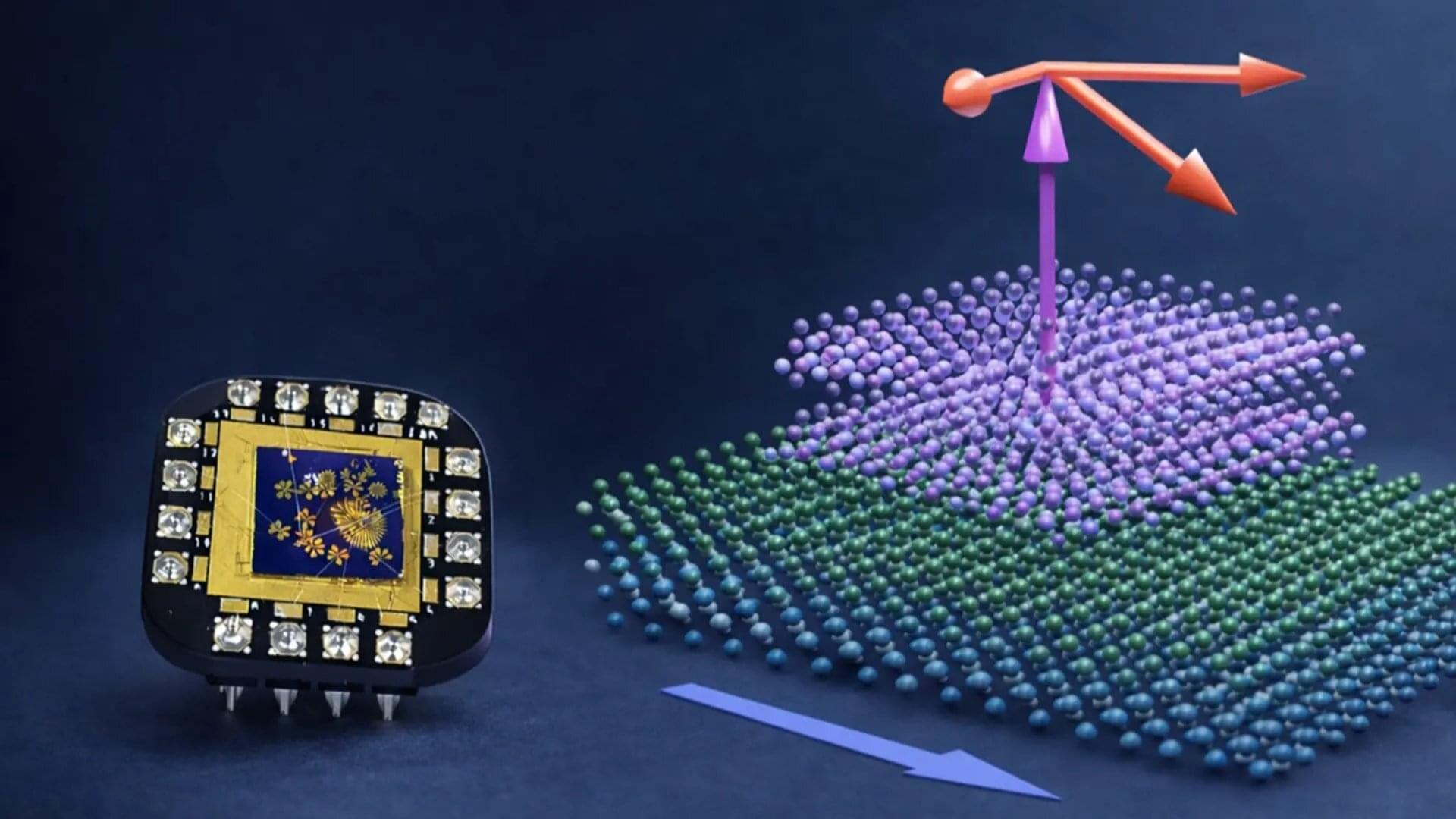

Making computer chips smaller is not just about better design. It also depends on a critical step in manufacturing called patterning, where nanoscale structures are carved into materials to form the circuits inside everything from smartphones to advanced sensors.

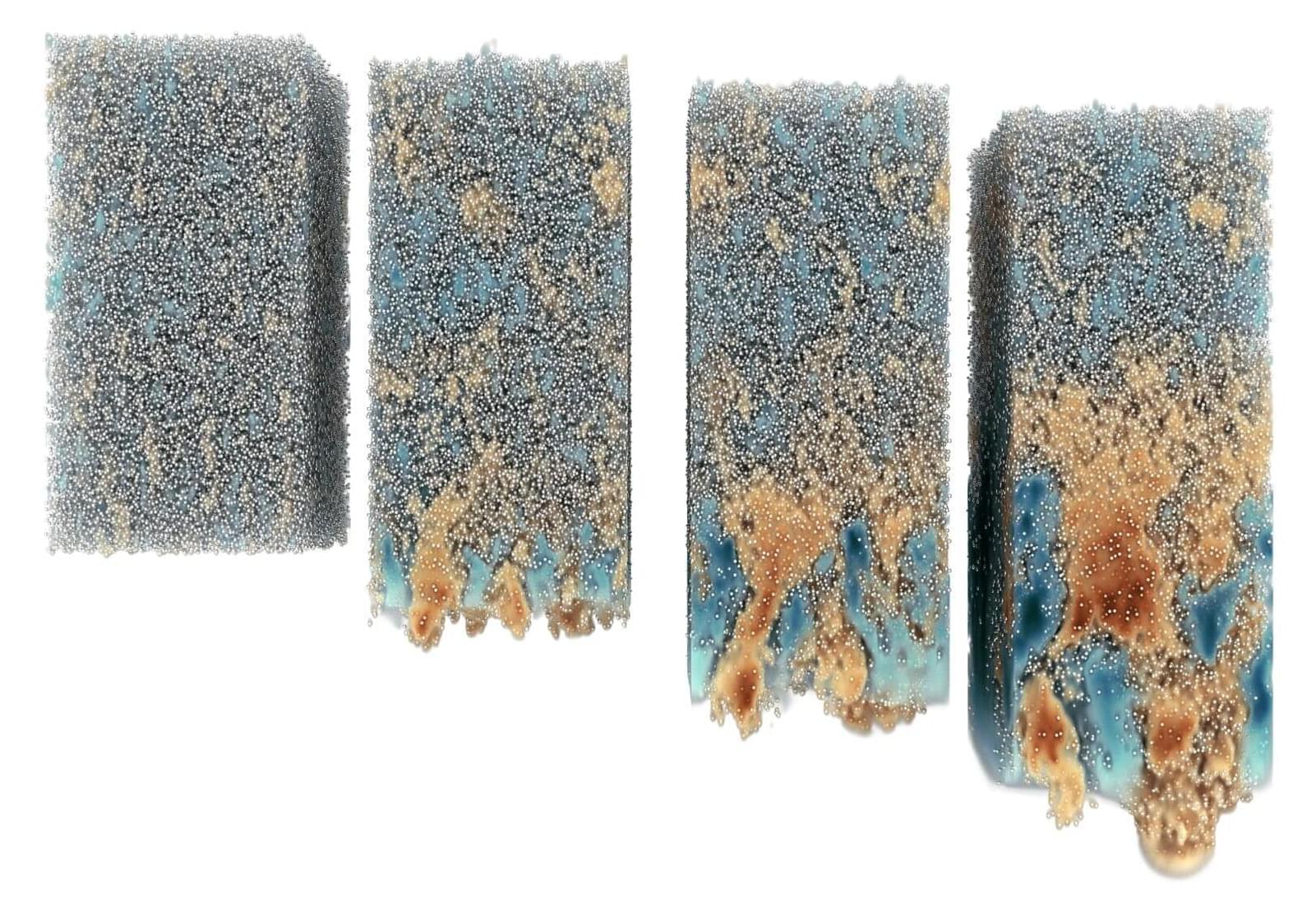

To create these patterns, engineers use a hard mask, a thin, durable material layer that protects selected regions while the exposed areas are etched away.

“As chips get smaller, the manufacturing process becomes much more demanding,” said Saptarshi Das, Penn State Ackley Professor of Engineering Science and professor of engineering science and mechanics. “The mask used to define these patterns must survive extremely harsh processing conditions. If the mask degrades, the patterns cannot be transferred reliably.”