Scientists have found a powerful new way to follow water as it moves around the planet—by tracking subtle “fingerprints” hidden inside its atoms.

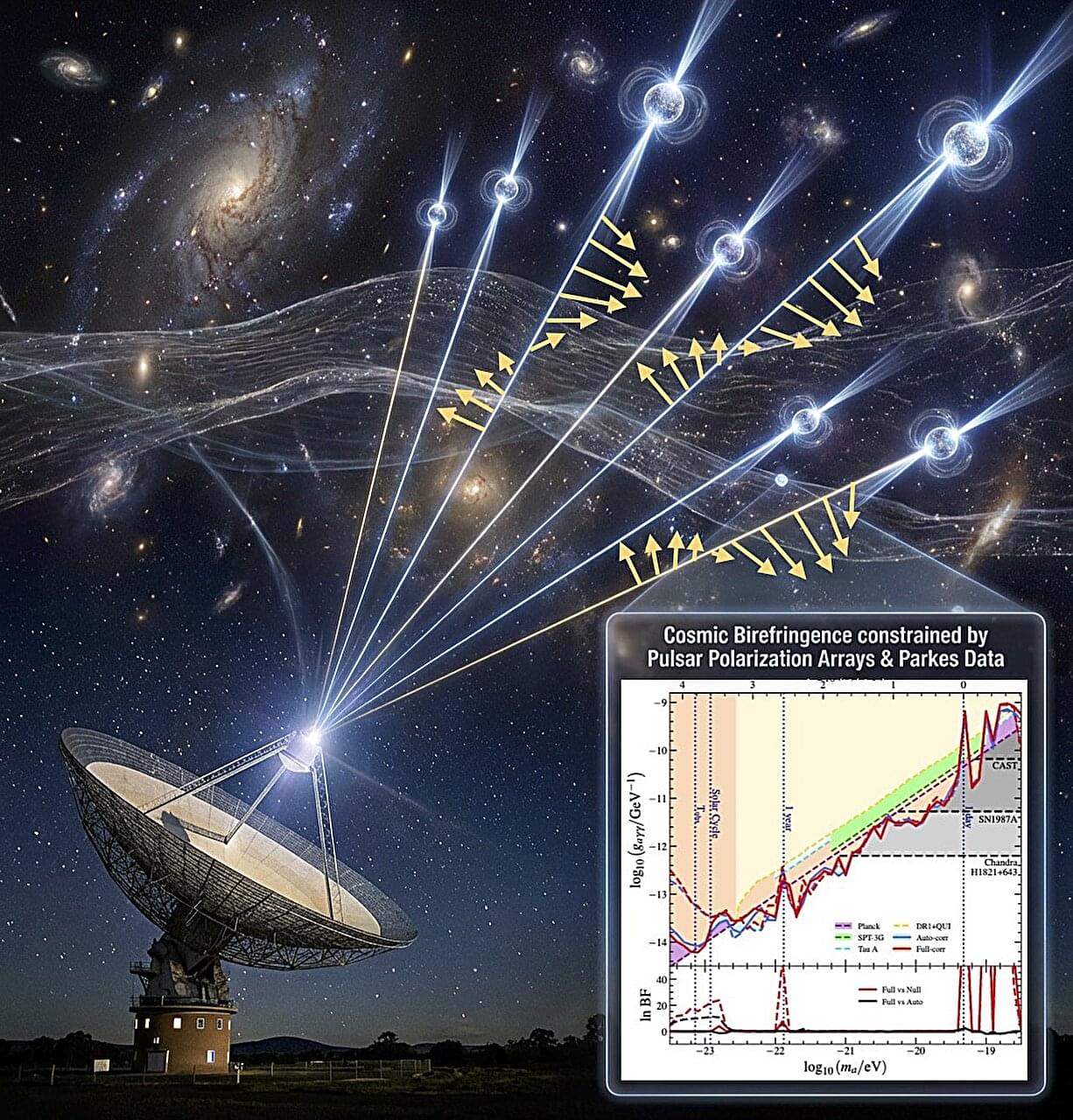

Dark matter is a type of matter that is predicted to make up most of the matter in the universe, yet it is very difficult to detect using conventional experimental techniques, as it does not emit, absorb, or reflect light. While some past studies gathered indirect hints of its existence, dark matter has never been directly observed; thus, its composition remains a mystery.

One hypothesis is that dark matter is made up of axionlike particles with an extremely low mass, broadly referred to as ultralight axionlike dark matter (ALDM). As these particles are exceedingly light, predictions suggest that they would behave more like waves than individual particles on a galactic scale.

The PPTA collaboration, a large team of researchers based at different institutes worldwide, applied a new approach to search for ALDM by cross-correlating polarization data of pulsars, neutron stars that spin rapidly and emit highly regular beams of radio waves. This approach, termed the “Pulsar Polarization Array (PPA),” entails measuring the polarization position angles of a series of pulsars and how they changed over time and with respect to pulsar spatial position.

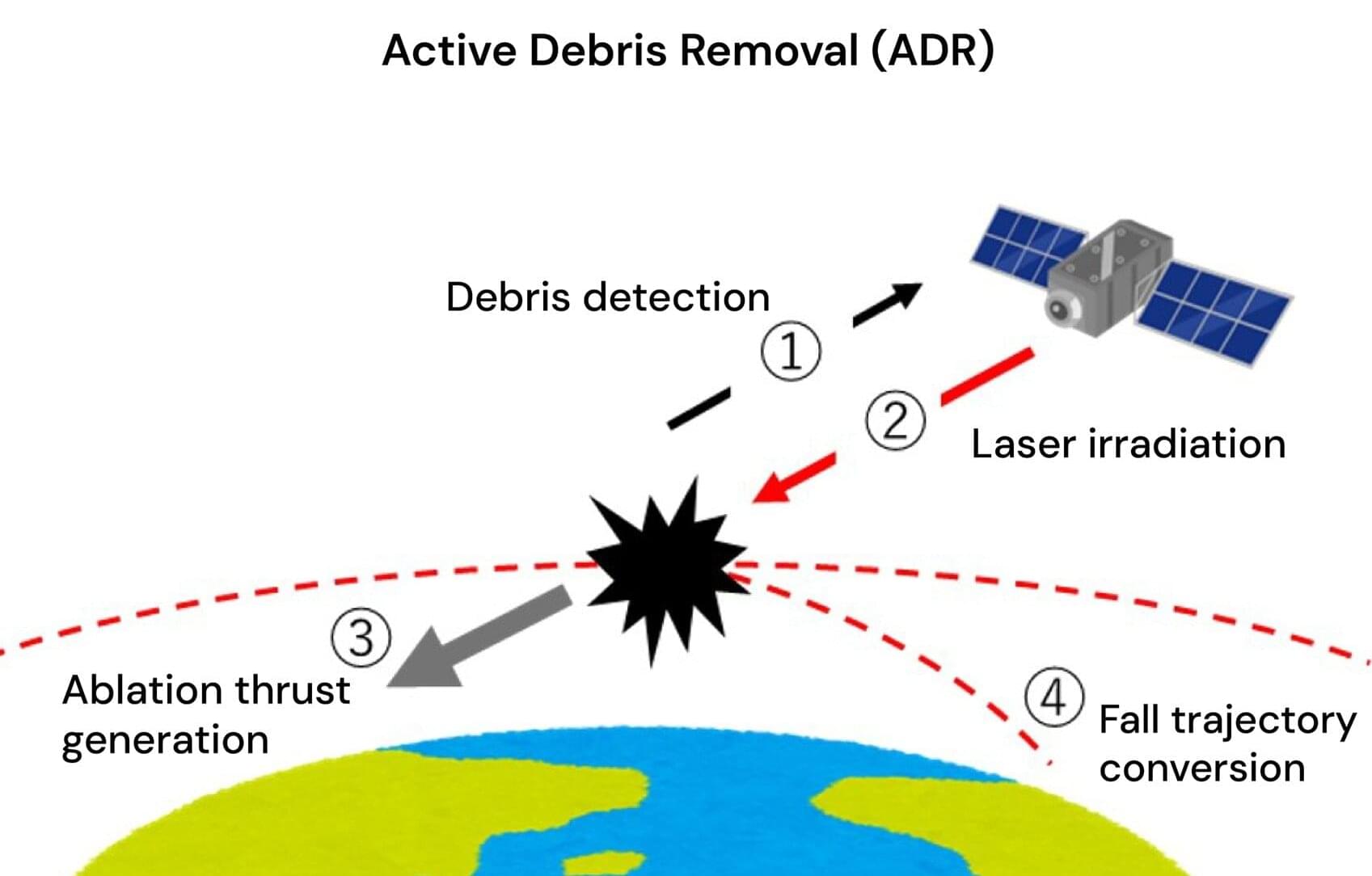

A possible alternative to active debris removal (ADR) by laser is ablative propulsion by a remotely transmitted electron beam (e-beam). The e-beam ablation has been widely used in industries, and it might provide higher overall energy efficiency of an ADR system and a higher momentum-coupling coefficient than laser ablation. However, transmitting an e-beam efficiently through the ionosphere plasma over a long distance (10 m–100 km) and focusing it to enhance its intensity above the ablation threshold of debris materials are new technical challenges that require novel methods of external actions to support the beam transmission.

Therefore, Osaka Metropolitan University researchers conducted a preliminary study of the relevant challenges, divergence, and instabilities of an e-beam in an ionospheric atmosphere, and identified them quantitatively through numerical simulations. Particle-in-cell simulations were performed systematically to clarify the divergence and the instability of an e-beam in an ionospheric plasma.

The major phenomena, divergence and instability, depended on the densities of the e-beam and the atmosphere. The e-beam density was set slightly different from the density of ionospheric plasma in the range from 1010 to 1012 m−3. The e-beam velocity was changed from 106 to 108 m/s, in a nonrelativistic range.

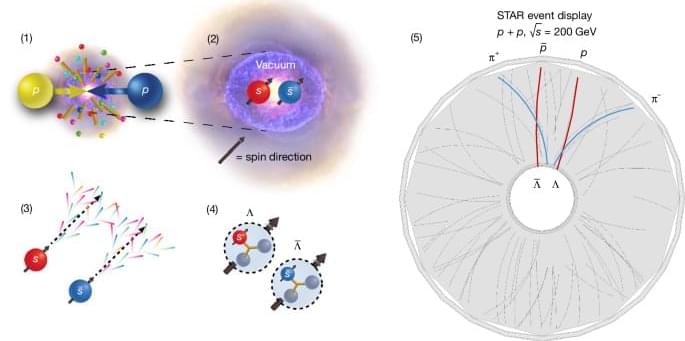

Just after 9 a.m. on Friday, Feb. 6, 2026, final beams of oxygen ions—oxygen atoms stripped of their electrons—circulated through the twin 2.4-mile-circumference rings of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and crashed into one another at nearly the speed of light inside the collider’s two house-sized particle detectors, STAR and sPHENIX. RHIC, a nuclear physics research facility at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory has been smashing atoms since the summer of 2000. The final collisions cap a quarter century of remarkable experiments using 10 different atomic species colliding over a wide range of energies in different configurations.

The RHIC program has produced groundbreaking discoveries about the building blocks of matter and the nature of proton spin and technological advances in accelerators, detectors, and computing that have far surpassed scientists’ expectations when this discovery machine first turned on.

“RHIC has been one of the most successful user facilities operated by the DOE Office of Science, serving thousands of scientists from across the nation and around the globe,” said DOE Under Secretary for Science Darío Gil. “Supporting these one-of-a-kind research facilities pushes the limits of technology and expands our understanding of our world through transformational science—central pillars of DOE’s mission to ensure America’s security and prosperity.”

Big Bang Thought of the Day by Nobel Laureate Peter Higgs, “The Big Bang made the universe explode into existence. The Higgs boson made it stay.” The universe formed 13.8 billion years ago. But matter could not exist without mass. In 1964, Peter Higgs proposed a solution. His Higgs boson explains why particles gained weight after the Big Bang. Confirmed in 2012 at CERN, it settled decades of cosmic theory conflicts. This discovery reshaped modern physics and cosmology forever.

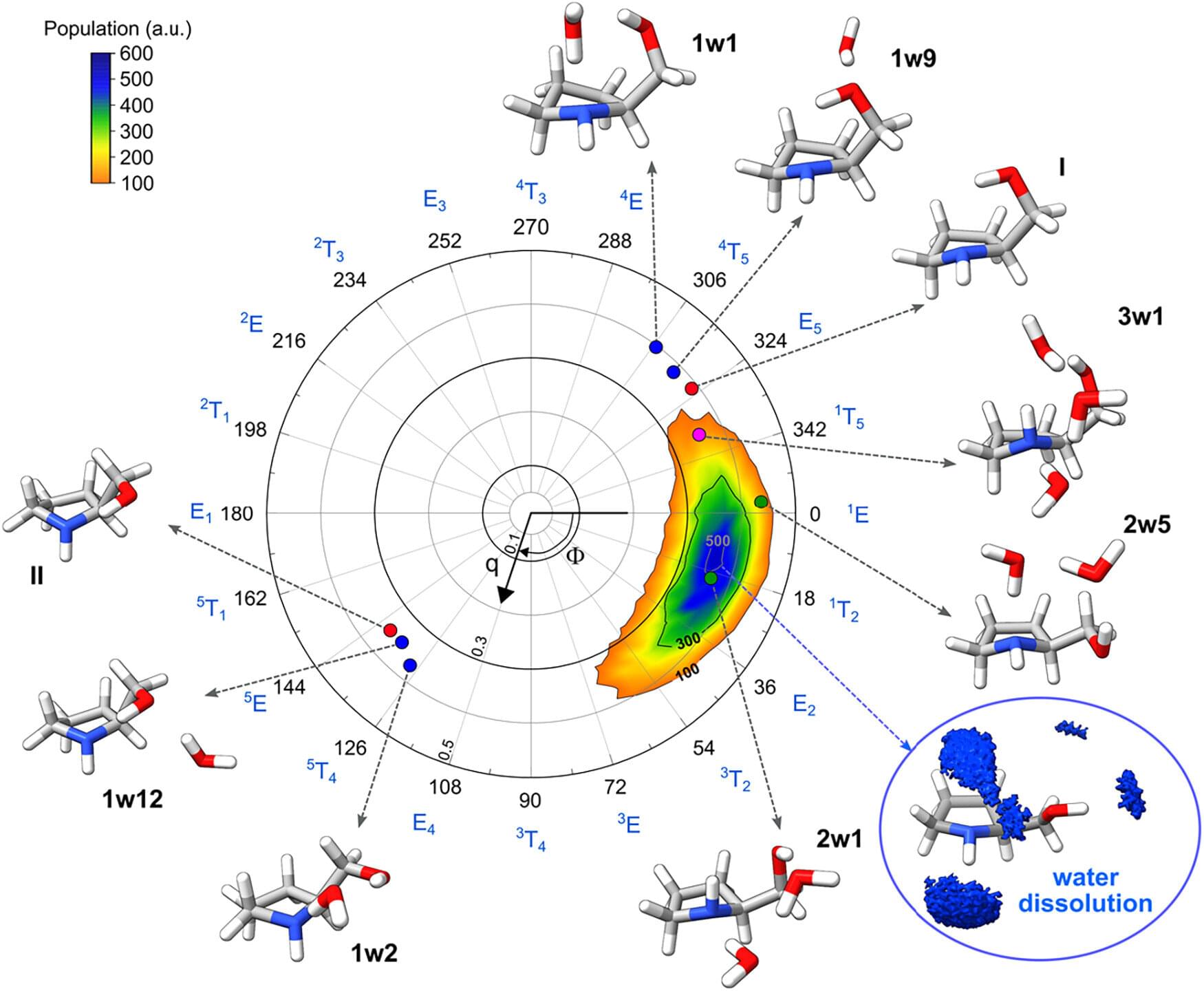

Researchers have analyzed the stepwise hydration of prolinol, a molecule widely used as a catalyst and as a building block in chemical synthesis. The study shows that just a few water molecules can completely change the preferred structure of prolinol. The research is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Physical chemistry applies the principles and concepts of physics to understand the basics of chemistry and explain how and why transformations of matter take place on a molecular level. One of the branches of this field focuses on understanding how molecules change in the course of a chemical reaction or process.

Understanding the interactions of chiral molecules with water is crucial, given the central role that water plays in chemical and biological processes. Chiral molecules are those that, despite comprising the same atoms, cannot be superimposed on their mirror image in a way similar to what happens with right and left hands or a pair of shoes.

Physicists at Heidelberg University have developed a new theory that finally unites two long-standing and seemingly incompatible views of how exotic particles behave inside quantum matter. In some cases, an impurity moves through a sea of particles and forms a quasiparticle known as a Fermi polaron; in others, an extremely heavy impurity freezes in place and disrupts the entire system, destroying quasiparticles altogether. The new framework shows these are not opposing realities after all, revealing how even very heavy particles can make tiny movements that allow quasiparticles to emerge.

Head to https://brilliant.org/Spacetime/ to start learning for free for 30 days. Plus, our viewers get 20% off an annual Premium subscription for unlimited daily access to everything Brilliant has to offer.

Physicists have long believed that detecting the particle of gravity—the graviton—was fundamentally impossible, with the universe itself seeming to block every direct attempt. This episode explores a new generation of clever experiments that may finally let us detect gravity’s particle, and why even succeeding wouldn’t quite mean what we think it does.

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

/ pbsspacetime.

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

Sign up for the mailing list to get episode notifications and hear special announcements!

https://mailchi.mp/1a6eb8f2717d/space… the Entire Space Time Library Here: https://search.pbsspacetime.com/ Hosted by Matt O’Dowd Written by Richard Dyer & Matt O’Dowd Post Production by Leonardo Scholzer Directed by Andrew Kornhaber Associate Producer: Bahar Gholipour Executive Producer: Andrew Kornhaber Executive in Charge for PBS: Maribel Lopez Director of Programming for PBS: Gabrielle Ewing Assistant Director of Programming for PBS: Mike Martin Spacetime is a production of Kornhaber Brown for PBS Digital Studios. This program is produced by Kornhaber Brown, which is solely responsible for its content. © 2026 PBS. All rights reserved. End Credits Music by J.R.S. Schattenberg: / multidroideka Space Time Was Made Possible In Part By: Big Bang Alexander Tamas David Paryente Juan Benet Mark Rosenthal Morgan Hough Peter Barrett Santiago Tj Steyn Vinnie Falco Supernova Ethan Cohen Glenn Sugden Grace Biaelcki Mark Heising Stephen Wilcox Tristan Lucian Claudius Aurelius Tyacke Hypernova Alex Kern Ben Delo Cal Stephens chuck zegar David Giltinan Dean Galvin Donal Botkin Gregory Forfa Jesse Cid Dyer John R. Slavik Justin Lloyd Kenneth See Massimiliano Pala Michael Tidwell Mike Purvis Paul Stehr-Green Scott Gorlick Scott Gray Spencer Jones Stephen Saslow Thomas Mouton Zachary Haberman Антон Кочков Daniel Muzquiz Gamma Ray Burst Aaron Pinto Adrien Molyneux Almog Cohen Anthony Leon Arko Provo Mukherjee Ayden Miller Ben McIntosh Bradley Jenkins Bradley Ulis Brandon Lattin Brian Cook Bryan White Chris Liao Christopher Wade Chuck Lukaszewski Collin Dutrow Craig Falls Craig Stonaha Dan Warren Daniel Donahue Daniel Jennings Daron Woods Darrell Stewart David Johnston Doyle Vann Eric Kiebler Eric Raschke Eric Schrenker Faraz Khan Frederic Simon Harsh Khandhadia Ian Williams Isaac Suttell James Trimmier Jeb Campbell Jeremy Soller Jerry Thomas jim bartosh John Anderson John De Witt John Funai John H. Austin, Jr. John591 Joseph Salomone Junaid Ali Kacper Cieśla Kane Holbrook Keith Pasko Kent Durham Koen Wilde Kyle Atkinson Marcelo Garcia Marion Lang Mark Daniel Cohen Mark Delagasse Matt Kaprocki Matthew Johnson Michael Barton Michael Clark Michael Lev Michael Purcell Nathaniel Bennett Nick Hoffenstoffer III Nicolas Katsantonis Paul Wood Rad Antonov Reuben Brewer Richard Steenbergen Robert DeChellis Ross Story Russell Moore SamSword Sandhya Devi Satwik Pani Sean Owen Shane Calimlim SilentGnome Sound Reason Steffen Bendel Steven Giallourakis Terje Vold Thomas Dougherty Tomaz Lovsin Tybie Fitzhugh Vlad Shipulin William Flinn WILLIAM HAY III Zac Sweers.

Search the Entire Space Time Library Here: https://search.pbsspacetime.com/