This new particle is so small it makes an atom look enormous.

Keeping high-power particle accelerators at peak performance requires advanced and precise control systems. For example, the primary research machine at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility features hundreds of fine-tuned components that accelerate electrons to 99.999% the speed of light.

The electrons get this boost from radiofrequency waves within a series of resonant structures known as cavities, which become superconducting at temperatures colder than deep space.

These cavities form the backbone of Jefferson Lab’s Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF), a unique DOE Office of Science user facility supporting the research of more than 1,650 nuclear physicists from around the globe. CEBAF also holds the distinction of being the world’s first large-scale installation and application of this superconducting radiofrequency (SRF) technology.

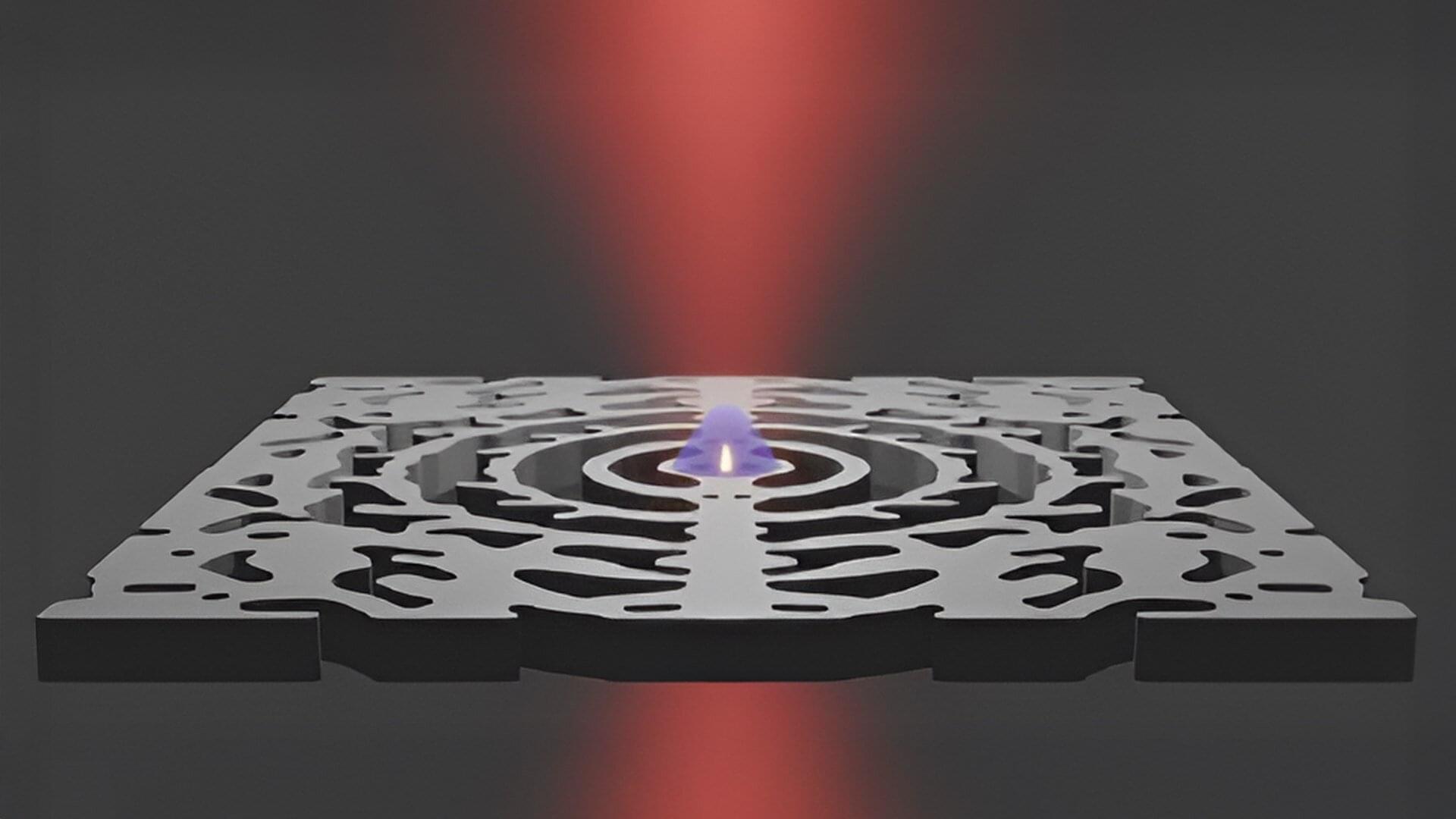

Researchers at DTU have developed a nanolaser that could be the key to much faster and much more energy-efficient computers, phones, and data centers. The technology offers the prospect of thousands of the new lasers being placed on a single microchip, thus opening a digital future where data is no longer transmitted using electrical signals, but using light particles, photons. The invention has been published in the journal Science Advances.

“The nanolaser opens up the possibility of creating a new generation of components that combine high performance with minimal size. This could be in information technology, for example, where ultra-small and energy-efficient lasers can reduce energy consumption in computers, or in the development of sensors for the health care sector, where the nanolaser’s extreme light concentration can deliver high-resolution images and ultrasensitive biosensors,” says DTU professor Jesper Mørk, who co-authored the paper together with, among others, Drs. Meng Xiong and Yi Yu from DTU Electro.

Technologies for energy storage as well as biological systems such as the network of neurons in the brain depend on driven electrolytes that are traveling in an electric field due to their electrical charges. This concept has also recently been used to engineer synthetic motors and molecular sensors on the nanoscale or to explain biological processes in nanopores. In this context, the role of the background medium, which is the solvent, and the resulting hydrodynamic fluctuations play an important role. Particles in such a system are influenced by these stochastic fluctuations, which effectively control their movements.

“When we imagine the environment inside a driven electrolyte at the nanoscale, we might think of a calm viscous medium in which ions move due to the electric field and slowly diffuse around. This new study reveals that this picture is wrong: the environment resembles a turbulent sea, which is highly nontrivial given the small scale,” explains Ramin Golestanian, who is director of the Department of Living Matter Physics at MPI-DS, and author of the study published in Physical Review Letters.

The research uncovers how the movement of the ions creates large-scale fluctuating fluid currents that stir up the environment and lead to fast motion of all the particles that are immersed in the environment, even if they are not charged.

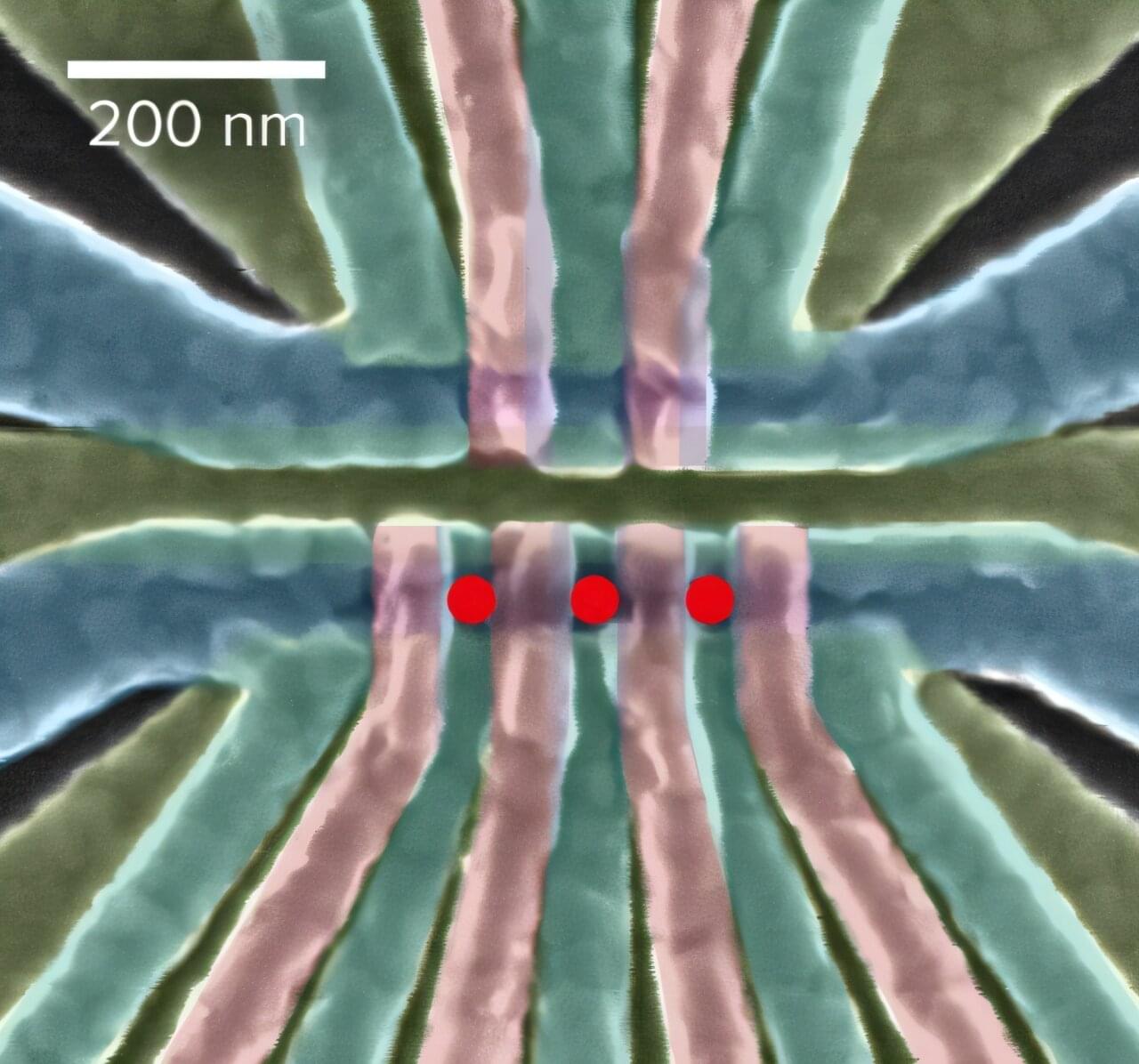

Devices that can confine individual electrons are potential building blocks for quantum information systems. But the electrons must be protected from external disturbances. RIKEN researchers have now shown how quantum information encoded into a so-called quantum dot can be negatively affected by nearby quantum dots. This has implications for developing quantum information devices based on quantum dots.

Quantum computers process information using so-called qubits: physical systems whose behavior is governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. An electron, if it can be isolated and controlled, is one example of a qubit platform with great potential.

One way of controlling an electron is to use a quantum dot. These tiny structures trap charged particles using electric fields at the tips of metal electrodes separated by just a few tens of nanometers.

Scientists say an ultra-powerful neutrino once thought impossible may be explained by an exotic black hole model involving a so-called “dark charge.”

As flour, plastic dust, and other powdery particles get blown through factory ducts, they become charged through contact with each other and with duct walls. To avoid discharges that could ignite explosions, ducts are metallic and grounded. Still, particles remain an explosive threat if they reach a silo while charged. The microphysics of contact charging is an active area of research, as is the quest to understand the phenomenon as it plays out on larger scales in dust storms, volcanic plumes, and processing plants. Now Holger Grosshans of the German National Metrology Institute in Braunschweig and his collaborators have developed a contact-charging model that can cope with particles and walls made of different materials [1]. What’s more, the model is compatible with computational approaches used to analyze large-scale turbulent flows.

The model treats particles’ acquisition of electric charge from each other and their surroundings as a stochastic process—one that involves some randomness. The resulting charge distributions depend on the amount of charge transferred per impact and other nanoscale parameters that would be tedious to measure for each system. Fortunately, Grosshans and his collaborators found that if they determined all parameters for one system in a controlled experiment, they could readily adjust the parameters to suit other systems.

To test their model, the researchers coupled it to a popular fluid-dynamics solver and simulated 300,000 polymer microparticles stirred by a turbulent flow while confined between four walls. The combination reproduced the complex charging patterns observed in lab experiments—and it did so efficiently: The charging model added less than 0.01% to the simulation’s computational cost.

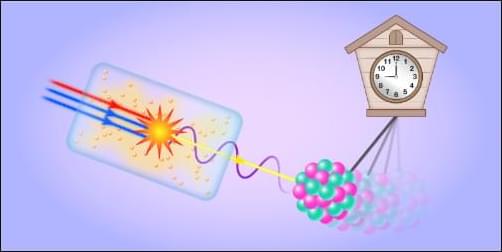

Researchers have designed and demonstrated an ultraviolet laser that removes a major bottleneck in the development of a nuclear clock.

Whereas ordinary atomic clocks keep time using transitions of electrons in atoms, a prospective nuclear clock would harness a transition between states of the nucleus. Compared with electronic transitions, nuclear ones are much less sensitive to environmental disturbances, which would potentially give nuclear clocks unprecedented precision and stability. Such devices could improve GPS systems and enable more sensitive probes of fundamental physics. The main hurdle has been that nuclear transitions are extremely difficult to drive controllably using existing laser technology. Now Qi Xiao at Tsinghua University in China and colleagues have proposed and realized an intense single-frequency ultraviolet laser that can achieve such driving for thorium-229 nuclei [1, 2]. Beyond timekeeping, the team’s laser platform could find uses across quantum information science, condensed-matter physics, and high-resolution spectroscopy.

For most nuclear transitions, the energy difference between the two states lies in the kilo-electron-volt to mega-electron-volt range. Consequently, such transitions are inaccessible to today’s high-precision lasers, which can deliver photons of typically a few electron volts in energy. A long-known exception is the transition between the ground state and first excited state of thorium-229 nuclei. Indirect measurements over the past 50 years have gradually pinned down that transition’s energy difference to only about 8.4 eV. As a result, this transition is being actively investigated as a candidate for developing a nuclear clock.