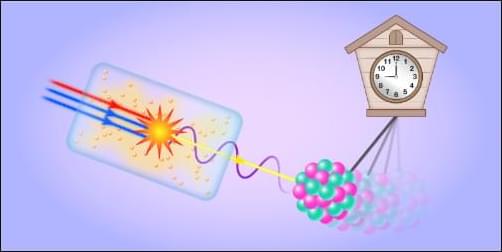

Technologies for energy storage as well as biological systems such as the network of neurons in the brain depend on driven electrolytes that are traveling in an electric field due to their electrical charges. This concept has also recently been used to engineer synthetic motors and molecular sensors on the nanoscale or to explain biological processes in nanopores. In this context, the role of the background medium, which is the solvent, and the resulting hydrodynamic fluctuations play an important role. Particles in such a system are influenced by these stochastic fluctuations, which effectively control their movements.

“When we imagine the environment inside a driven electrolyte at the nanoscale, we might think of a calm viscous medium in which ions move due to the electric field and slowly diffuse around. This new study reveals that this picture is wrong: the environment resembles a turbulent sea, which is highly nontrivial given the small scale,” explains Ramin Golestanian, who is director of the Department of Living Matter Physics at MPI-DS, and author of the study published in Physical Review Letters.

The research uncovers how the movement of the ions creates large-scale fluctuating fluid currents that stir up the environment and lead to fast motion of all the particles that are immersed in the environment, even if they are not charged.