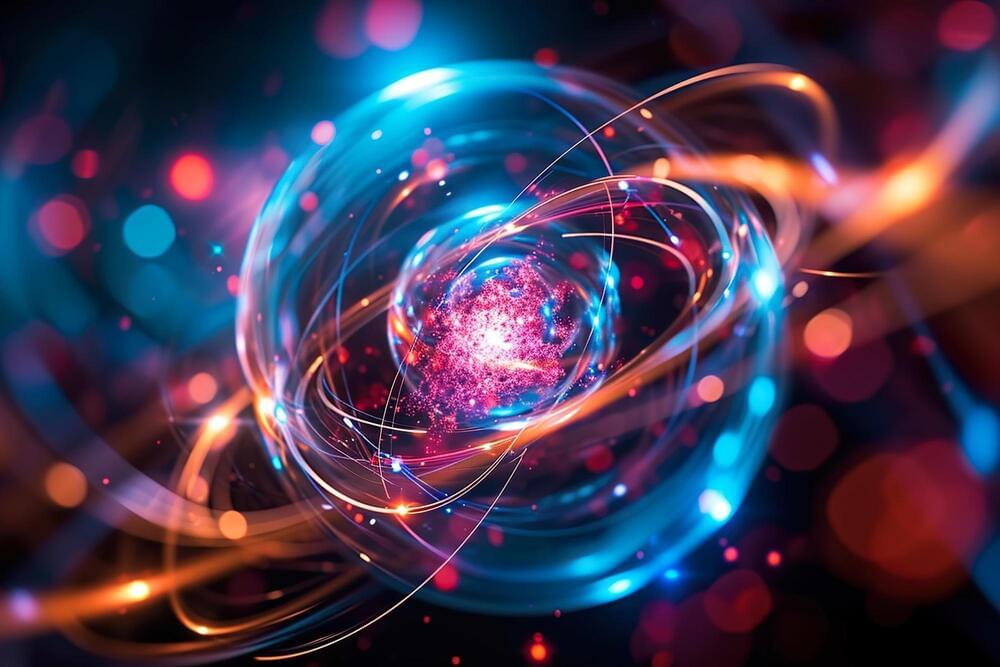

Research reveals the secrets of non-Heisenberg Tsai-type crystals that could open doors to applications in spintronics and magnetic refrigeration.

In 1960, Luttinger proposed a universal principle connecting the total capacity of a system for particles with its response to low-energy excitations. Although easily confirmed in systems with independent particles, this theorem remains applicable in correlated quantum systems characterized by intense inter-particle interactions.

However, and quite surprisingly, Luttinger’s theorem has been shown to fail in very specific and exotic instances of strongly correlated phases of matter. The failure of Luttinger’s theorem and its consequences on the behavior of quantum matter are at the core of intense research in condensed matter physics.

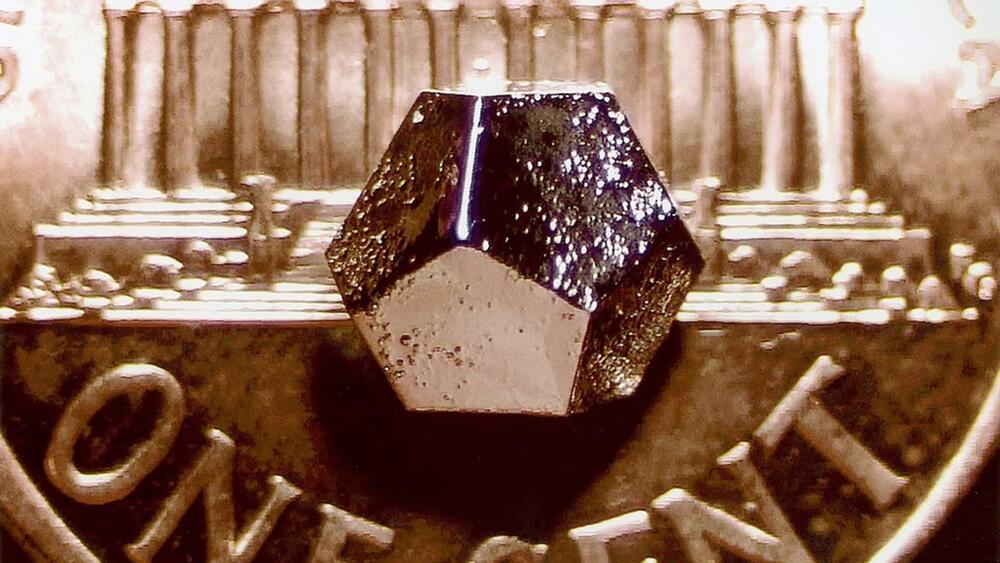

Quasicrystals are intermetallic materials that have garnered significant attention from researchers aiming to advance condensed matter physics understanding. Unlike normal crystals, in which atoms are arranged in an ordered repeating pattern, quasicrystals have non-repeating ordered patterns of atoms.

Their unique structure leads to many exotic and interesting properties, which are particularly useful for practical applications in spintronics and magnetic refrigeration.

A unique quasicrystal variant, known as the Tsai-type icosahedral quasicrystal (iQC) and their cubic approximant crystals (ACs), display intriguing characteristics. These include long-range ferromagnetic (FM) and anti-ferromagnetic (AFM) orders, as well as unconventional quantum critical phenomenon, to name a few.

Eighteen months ago, it was shown that different parts of the interior of the proton must be maximally quantum entangled with each other. This result, achieved with the participation of Prof. Krzysztof Kutak from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow and Prof. Martin Hentschinski from the Universidad de las Americas Puebla in Mexico, was a consequence of considerations and observations of collisions of high-energy photons with quarks and gluons in protons and supported the hypothesis presented a few years earlier by professors Dimitri Kharzeev and Eugene Levin.

Now, in a paper published in the journal Physical Review Letters, an international team of physicists has been presented a complementary analysis of entanglement for collisions between photons and protons in which secondary particles (hadrons) are produced by a process called diffractive deep inelastic scattering. The main question was: does entanglement also occur among quarks and gluons in these cases, and if so, is it also maximal?

Putting it in simple terms, physicists speak of entanglement between various quantum objects when the values of some feature of these objects are related. Quantum entanglement is not observed in the classical world, but its essence is easily explained by the toss of two coins. Each coin has two sides, and when it falls, it can take one of two mutually exclusive values (heads or tails) with the same probability.

In this episode, reporter Miryam Naddaf joins us to talk about the big science events to look out for in 2024. We’ll hear about the mass of the neutrino, the neural basis of consciousness and the climate lawsuits at the Hague, to name but a few.

Hear the biggest stories from the world of science | 6 January 2023.

Columbia University researchers have synthesized the first 2D heavy fermion material, CeSiI, a breakthrough in material science. This new material, easier to manipulate than traditional 3D heavy fermion compounds, opens up new possibilities in understanding quantum phenomena, including superconductivity. Credit: SciTechDaily.com.

Columbia University ’s creation of CeSiI, the first 2D heavy fermion material, marks a significant advancement in quantum material science. This development paves the way for new research into quantum phenomena and the design of innovative materials.

Researchers at Columbia University have successfully synthesized the first 2D heavy fermion material. They introduce the new material, a layered intermetallic crystal composed of cerium, silicon, and iodine (CeSiI), in a research article published today (January 17) in the scientific journal Nature.

This experimental milestone allows for the preservation of quantum information even when entanglement is fragile.

For the first time, researchers from the Structured Light Laboratory (School of Physics) at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, led by Professor Andrew Forbes, in collaboration with string theorist Robert de Mello Koch from Huzhou University in China (previously from Wits University), have demonstrated the remarkable ability to perturb pairs of spatially separated yet interconnected quantum entangled particles without altering their shared properties.

“We achieved this experimental milestone by entangling two identical photons and customizing their shared wave-function in such a way that their topology or structure becomes apparent only when the photons are treated as a unified entity,” explains lead author, Pedro Ornelas, an MSc student in the structured light laboratory.

When large stars or celestial bodies explode near Earth, their debris can reach our solar system. Evidence of these cosmic events is found on Earth and the Moon, detectable through accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). An overview of this exciting research was recently published in the scientific journal Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science by Prof. Anton Wallner of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), who soon plans to decisively advance this promising branch of research with the new, ultrasensitive AMS facility “HAMSTER.”

In their paper, HZDR physicist Anton Wallner and colleague Prof. Brian D. Fields from the University of Illinois in Urbana, USA, provide an overview of near-Earth cosmic explosions with a particular focus on events that occurred three and, respectively, seven million years ago.

“Fortunately, these events were still far enough away, so they probably did not significantly impact the Earth’s climate or have major effects on the biosphere. However, things get really uncomfortable when cosmic explosions occur at a distance of 30 light-years or less,” Wallner explains. Converted into the astrophysical unit parsec, this corresponds to less than eight to ten parsecs.

Large, low-background detectors using xenon as a target medium are widely used in fundamental physics, particularly in experiments searching for dark matter or studying rare decays of atomic nuclei. In these detectors, the weak interaction of a neutral particle—such as a neutrino—with a xenon-136 nucleus can transform it into a cesium-136 nucleus in a high-energy excited state.

The gamma rays emitted as the cesium-136 relaxes from this excited state could allow scientists to separate rare signals from background radioactivity. This can enable new measurements of solar neutrinos and more powerful searches for certain models of dark matter. However, searching for these events has been difficult due to a lack of reliable nuclear data for cesium-136. Researchers need to know the properties of cesium-136’s excited states, which have never been measured for this isotope.

This research, appearing in Physical Review Letters, provides direct determination of the relevant data by measuring gamma-ray emission from cesium-136 produced in nuclear reactions at a particle accelerator. Importantly, this research reveals the existence of so-called “isomeric states”—excited states that exist for approximately 100ns before relaxing to the ground state.

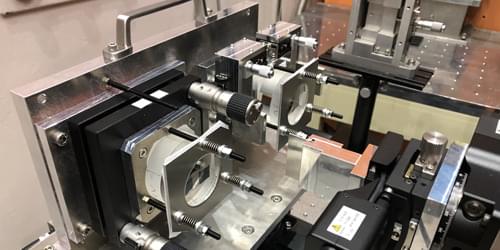

Researchers have demonstrated a mirror-based neutron interferometer that should be more sensitive to beyond-standard-model particle interactions than previous instruments.

Some theories of beyond-standard-model physics predict that neutrons passing close to an atomic nucleus will experience exotic interactions with the particles in that nucleus. To try to spot these interactions, physicists use a neutron interferometer, a device that splits and then recombines a neutron beam. If a currently unknown particle interaction affects one branch of the split beam as it passes through a material, the signature should show up in the interference pattern that forms when the two beams come back together. Takuhiro Fujiie at Nagoya University, Japan, and colleagues have now demonstrated a new neutron interferometer that promises greater sensitivity to beyond-standard-model physics [1].

In a conventional neutron interferometer, components made of crystalline silicon manipulate the neutron beam. Such interferometers only work for neutron beams that have wavelengths between 0.19 and 0.44 nm because of the spacings between crystalline silicon’s atoms. In the new instrument, neutron mirrors composed of alternating layers of nickel and titanium manipulate the neutron beam. The spacing of the layers determines the wavelength reflected and can be tuned to make mirrors that work for a wider range of neutron-beam wavelengths—including longer wavelengths that offer greater measurement sensitivity.