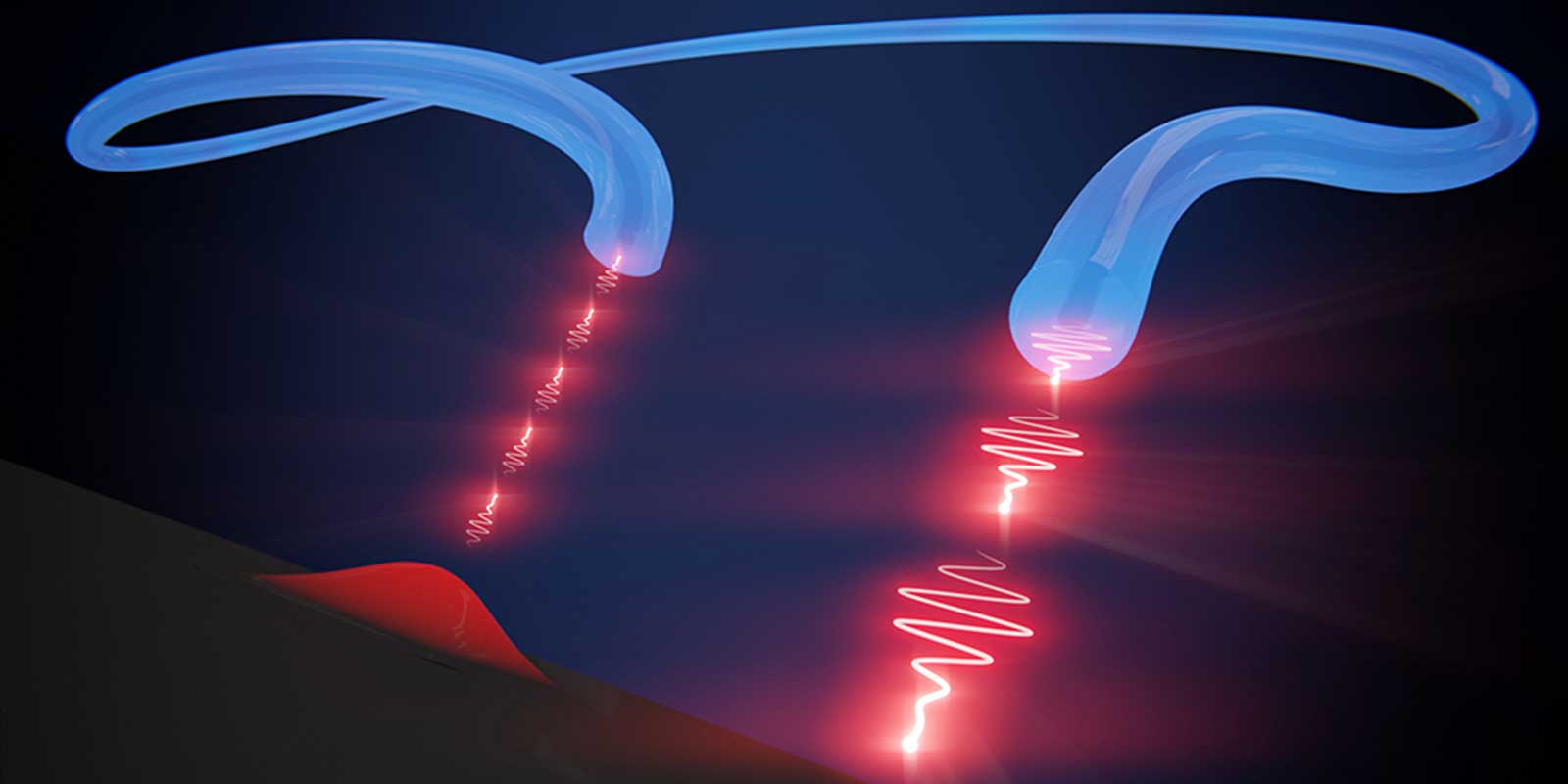

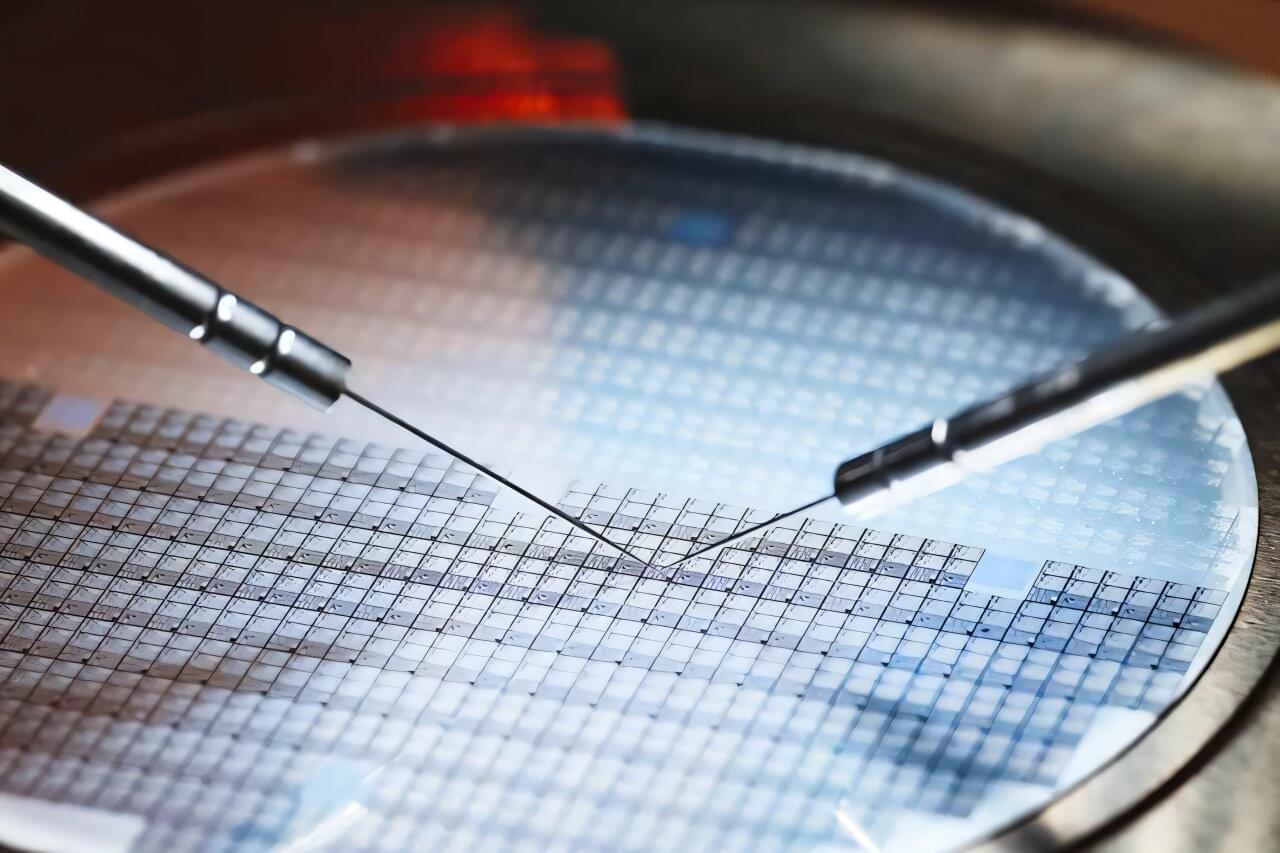

A group of Carnegie Mellon University researchers recently devised a method allowing them to create large amounts of a material required to make two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors with record high performance. Their paper, published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces in late December 2024, could lead to more efficient and tunable photodetectors, paving the way for the next generation of light-sensing and multifunctional optoelectronic devices.

“Semiconductors are the key enabling technology for today’s electronics, from laptops to smartphones to AI applications,” said Xu Zhang, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering. “They control the flow of electricity, acting as a bridge between conductors (which allow electricity to flow freely) and insulators (which block it).”

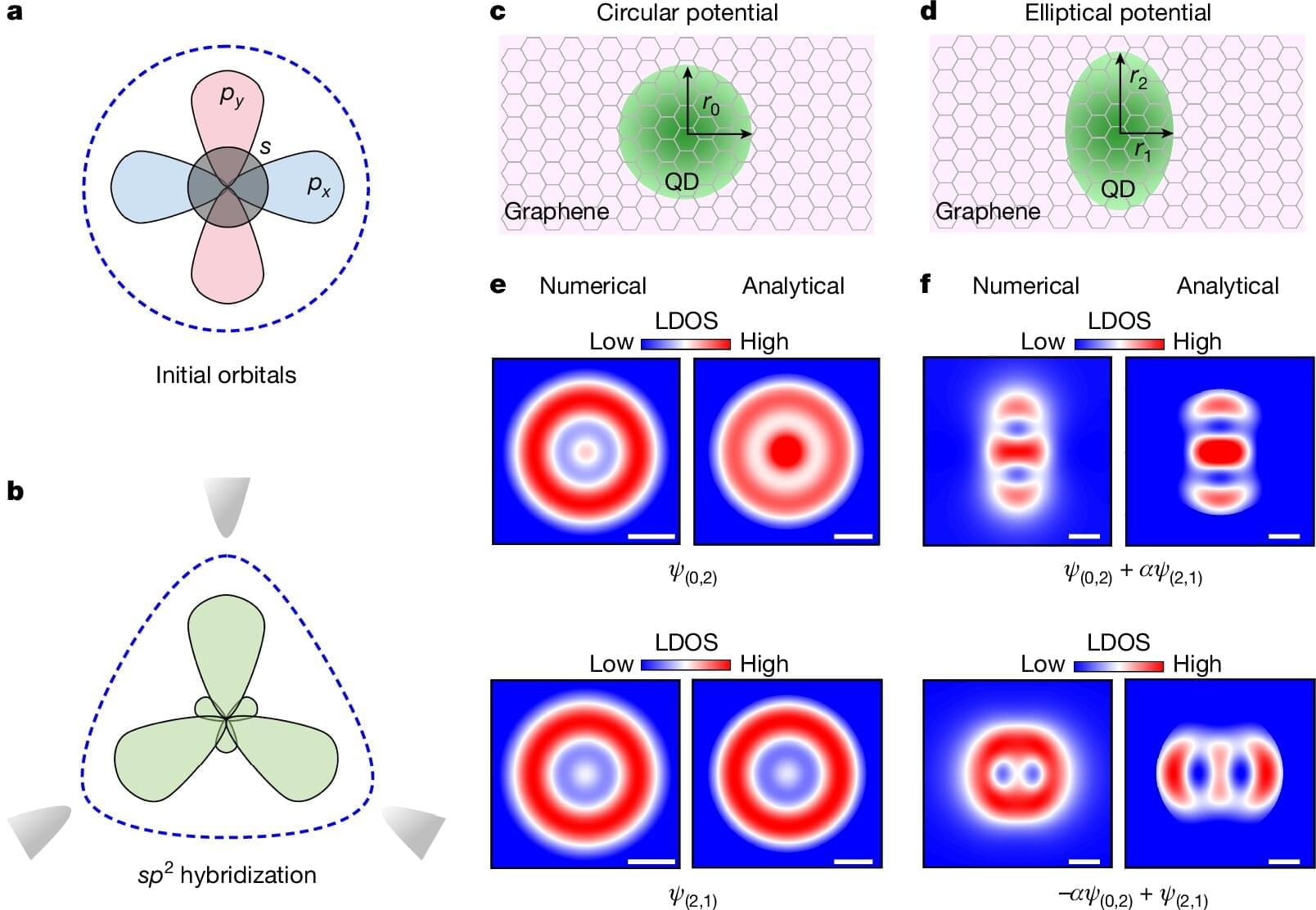

Zhang’s research group wanted to develop a certain kind of photodetector, a device capable of detecting light and which can be used in a variety of applications. To create this photodetector, the group needed to use materials that were an atom’s-width thick, or as close to 2D as is possible.