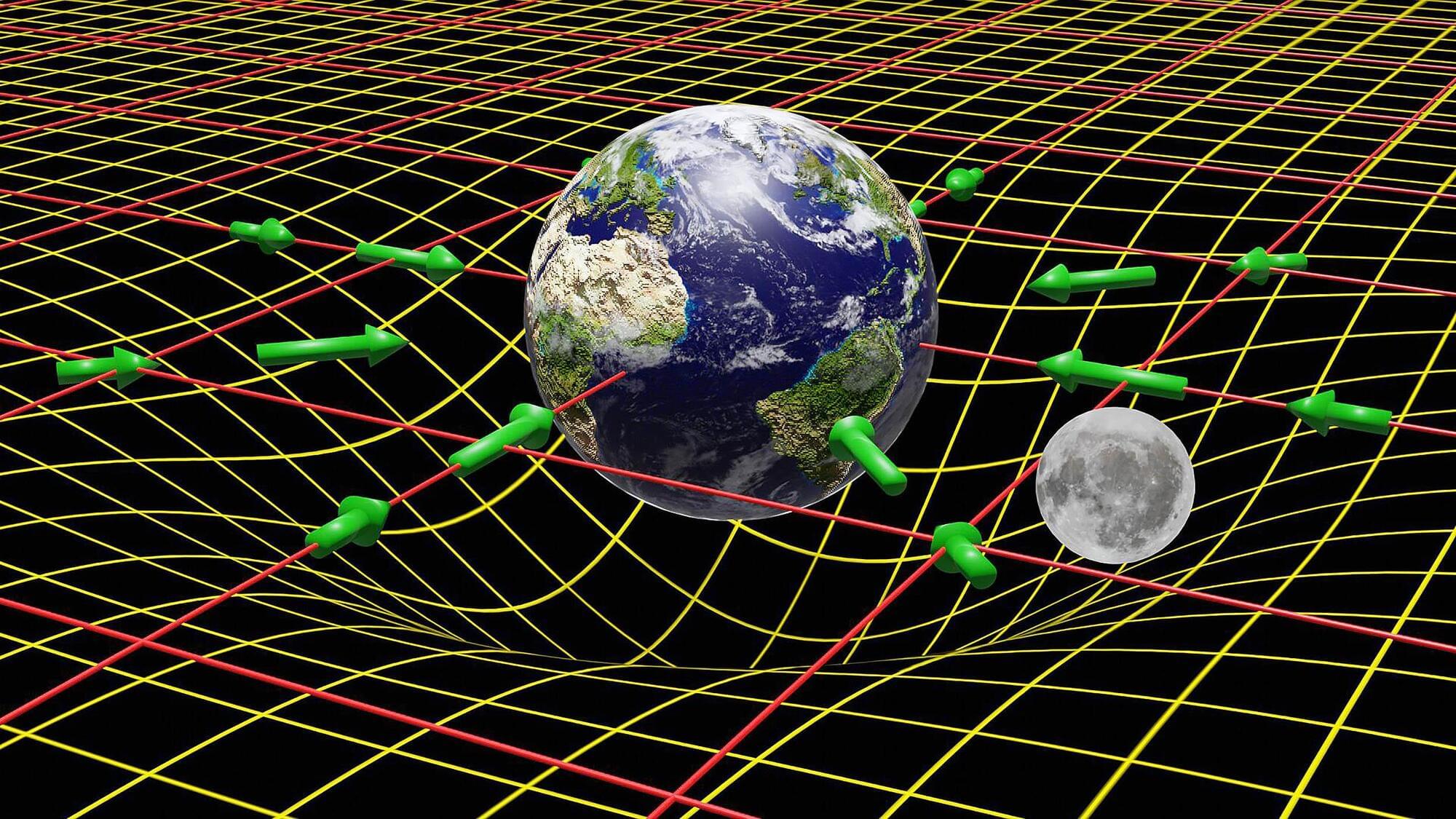

Future space missions could use quantum technologies to help us understand the physical laws that govern the universe, explore the composition of other planets and their moons, gain insights into unexplained cosmological phenomena, or monitor ice sheet thickness and the amount of water in underground aquifers on Earth.

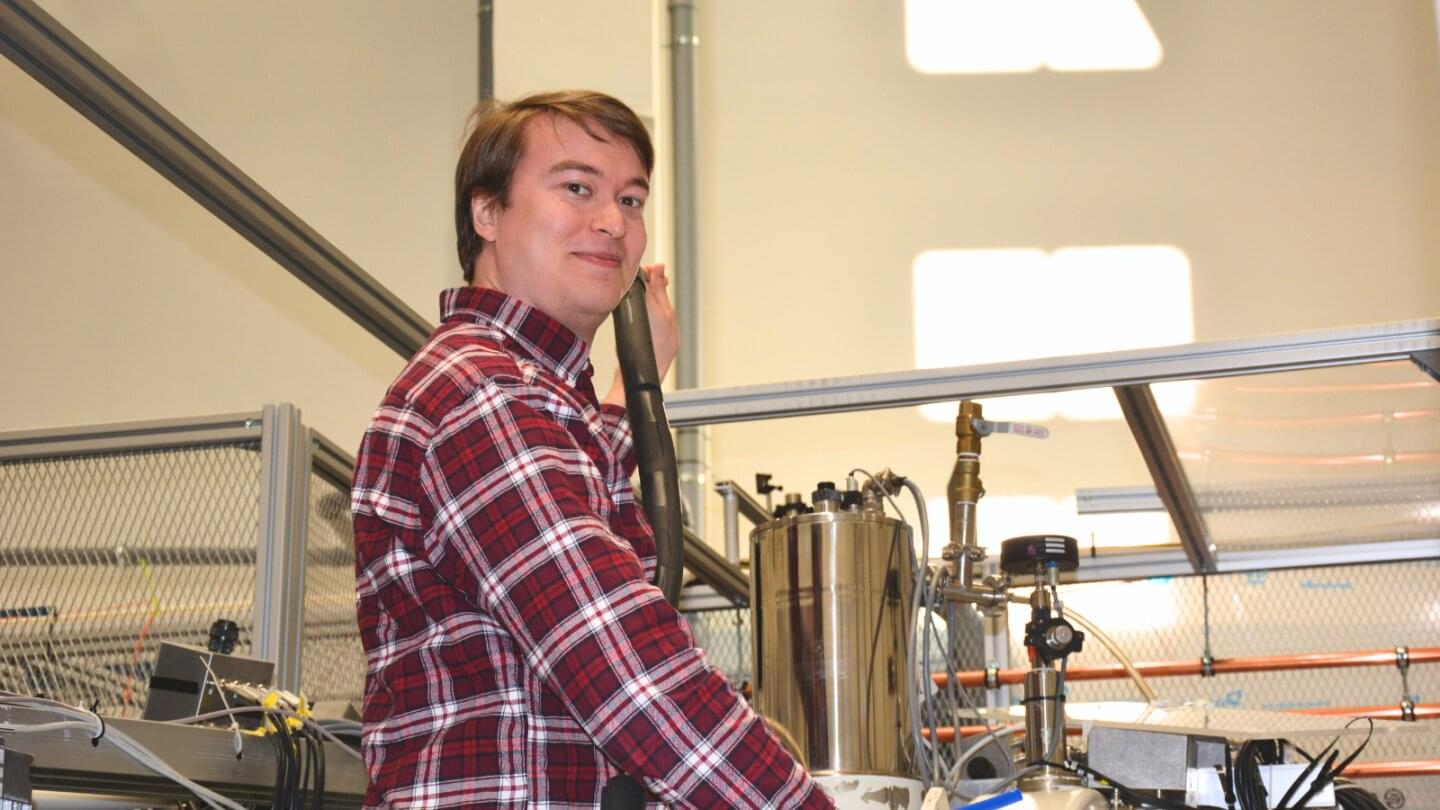

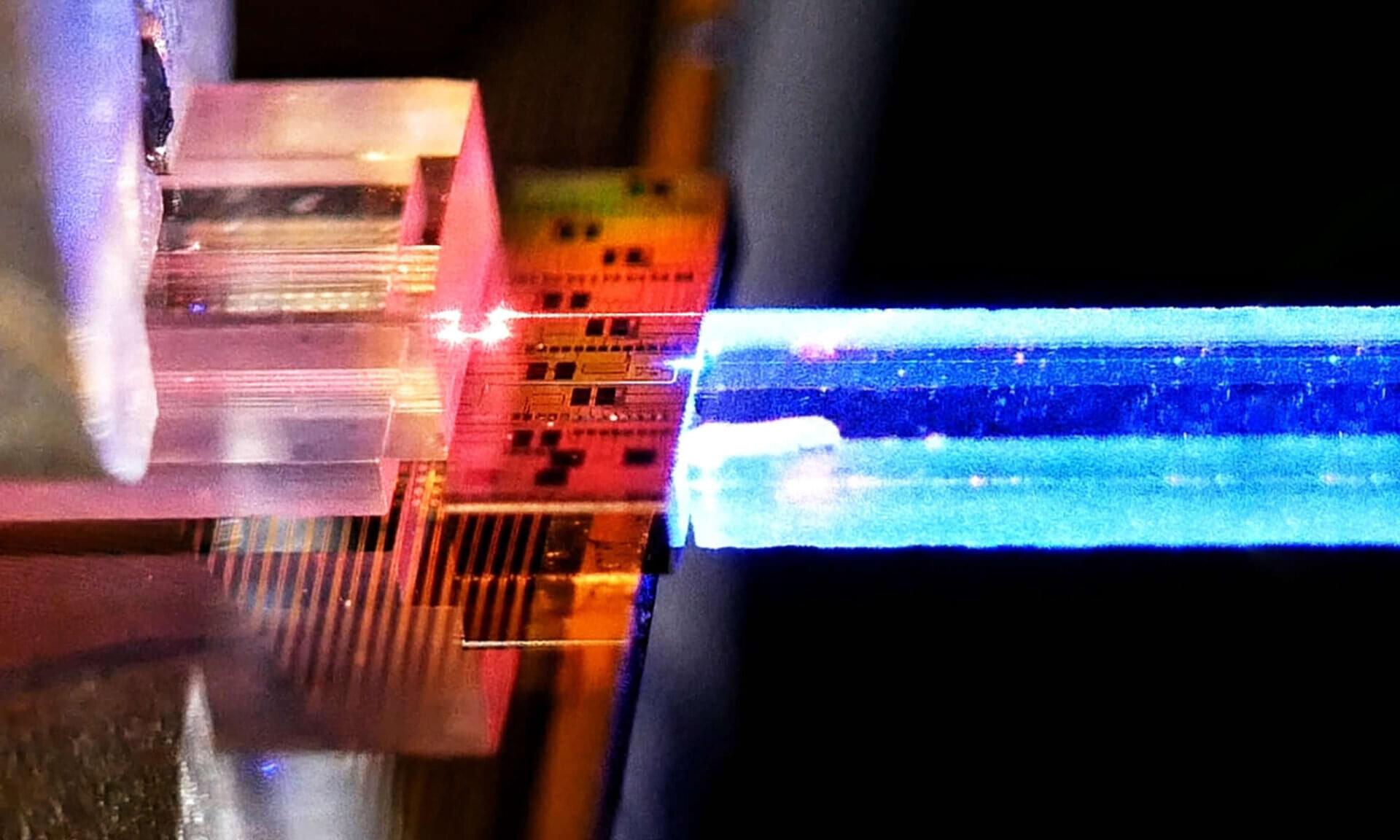

NASA’s Cold Atom Lab (CAL), a first-of-its-kind facility aboard the International Space Station, has performed a series of trailblazing experiments based on the quantum properties of ultracold atoms. The tool used to perform these experiments is called an atom interferometer, and it can precisely measure gravity, magnetic fields, and other forces.

Atom interferometers are currently being used on Earth to study the fundamental nature of gravity and are also being developed to aid aircraft and ship navigation, but use of an atom interferometer in space will enable innovative science capabilities.