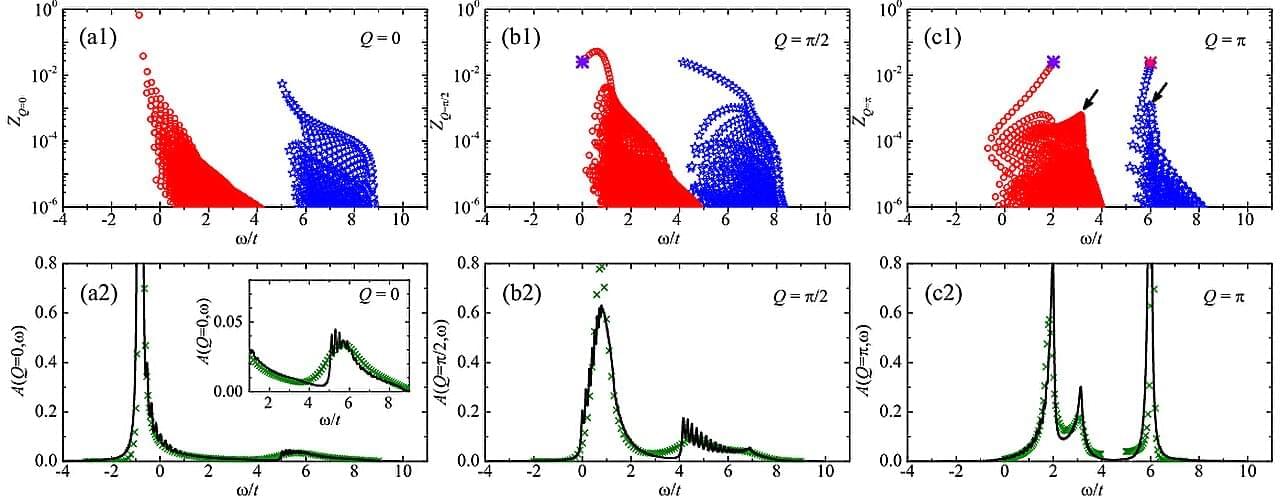

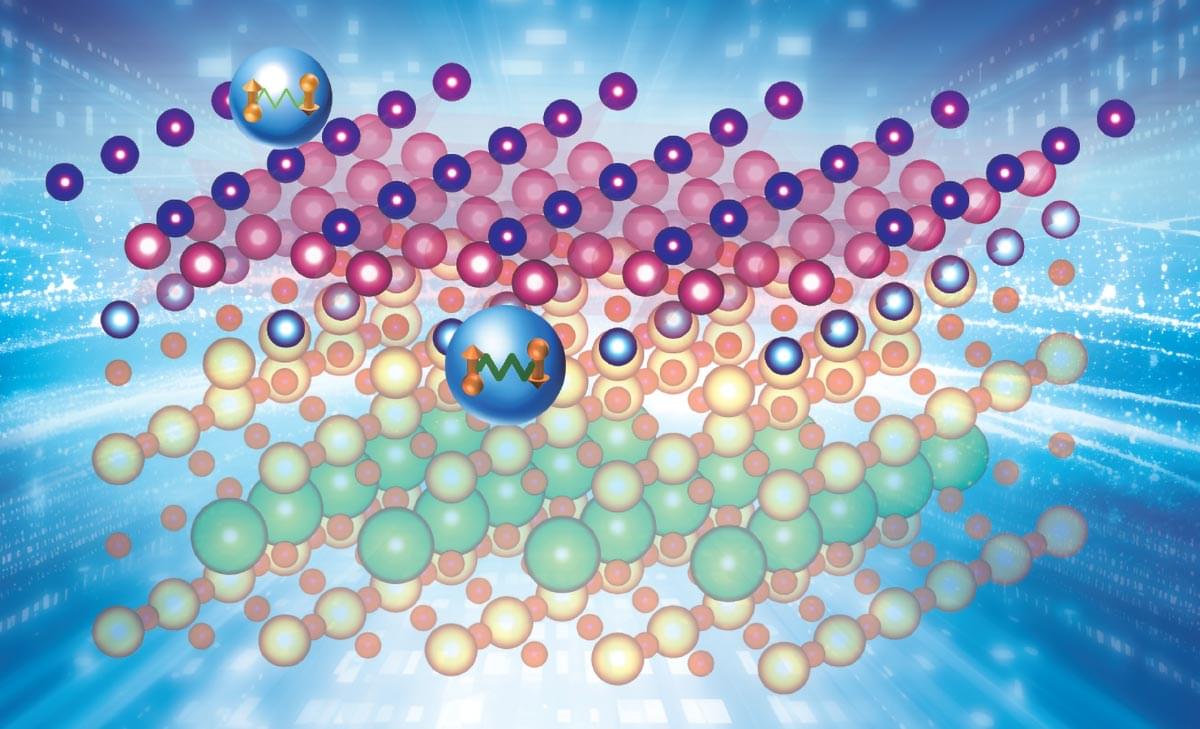

Swinburne researchers have discovered unexpected and entirely new quantum behaviors that only occur in one-dimensional systems, such as electrical current. Their new paper, published in Physical Review Letters, explores a fundamental question in quantum physics: what happens when a single “impurity” particle, such as an atom or electron, is introduced into a tightly packed crowd of identical particles.

Nearly every material in the world contains small imperfections or extra particles; understanding how these “outsiders” interact with their environment is key to figuring out how materials conduct electricity, create light, or respond to external forces.

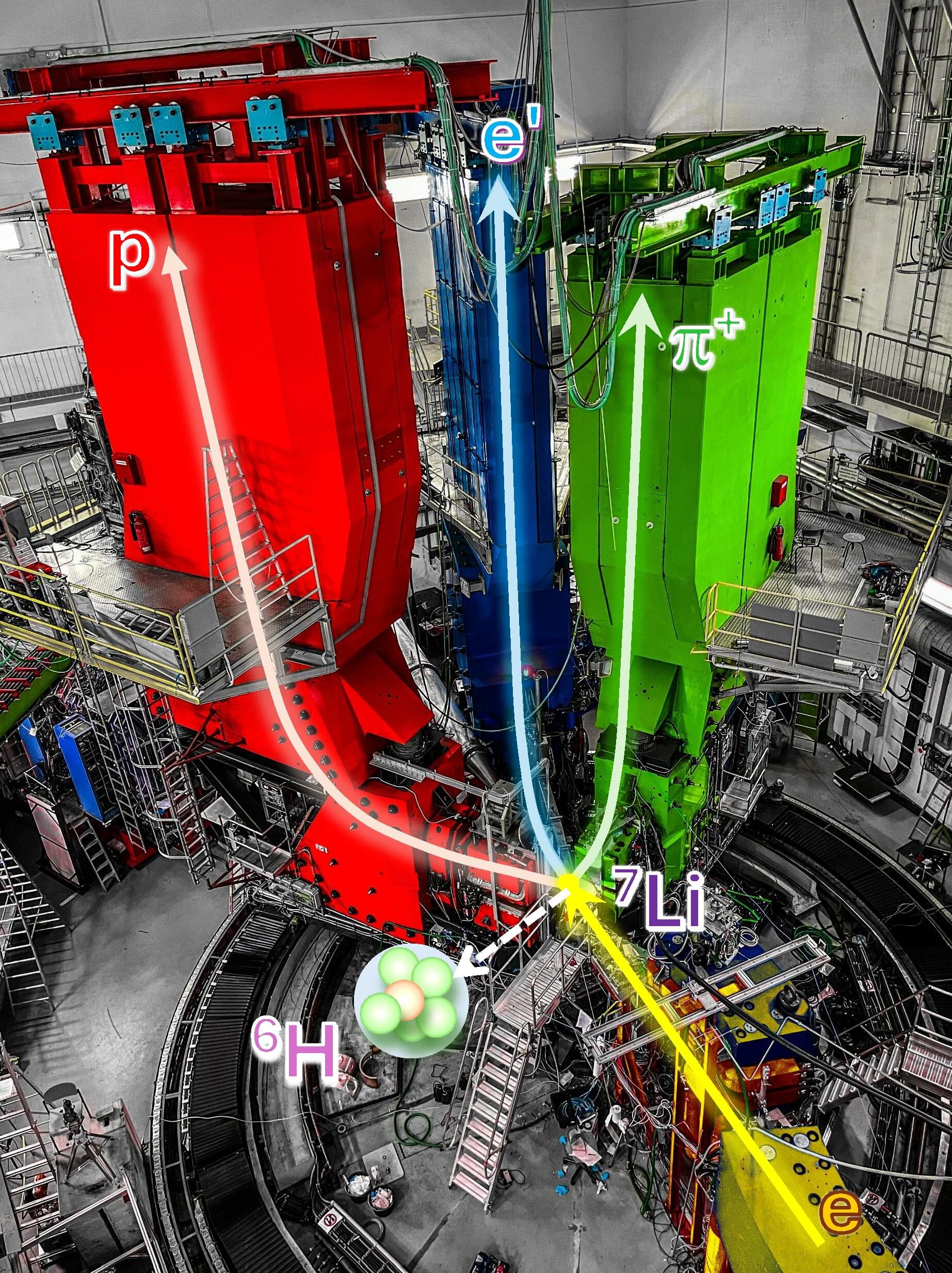

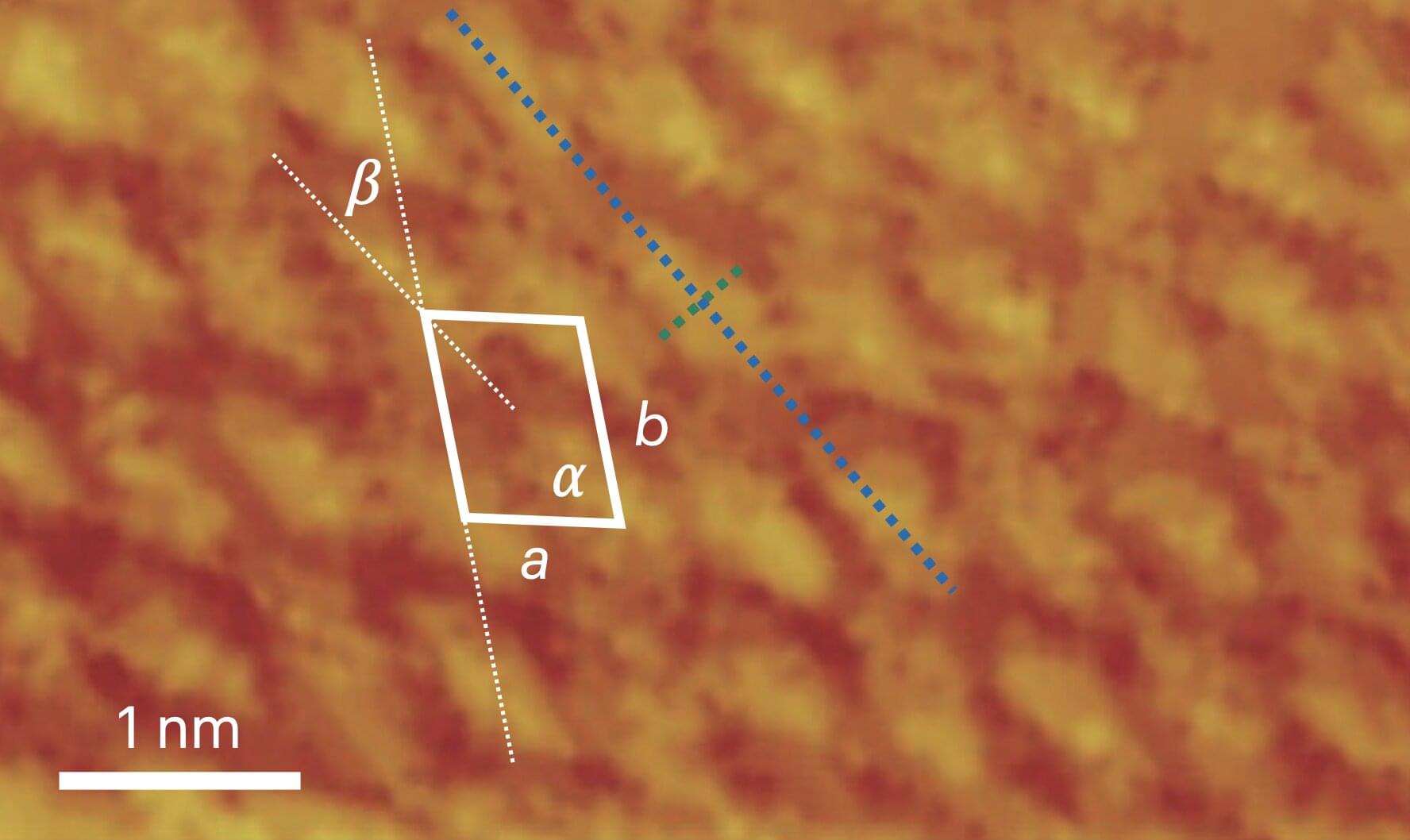

A team at the Center for Quantum Technology Theory at Swinburne studied this in the setting of a one-dimensional optical lattice (a kind of artificial crystal made with laser light) using a well-known theoretical framework called the Fermi-Hubbard model.