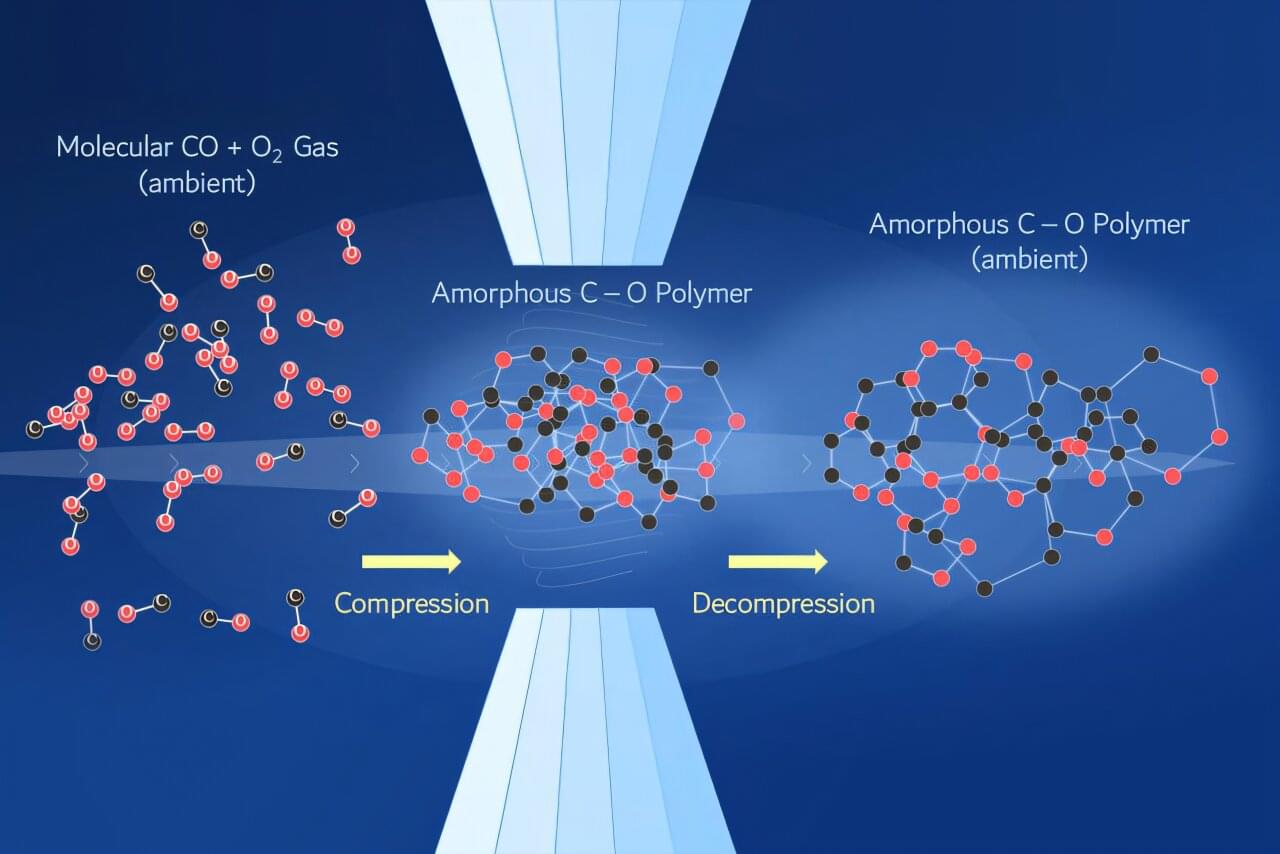

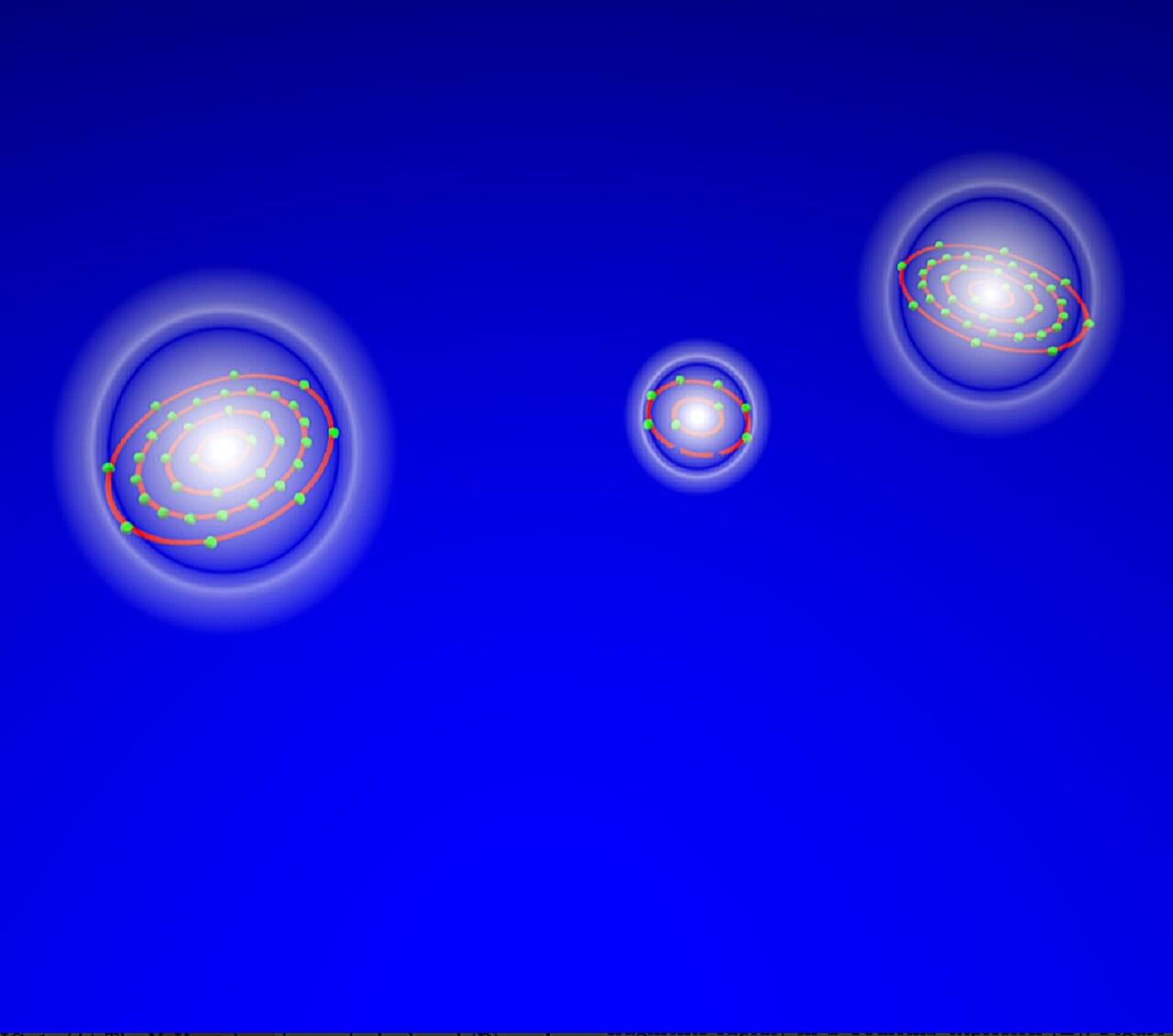

Together with an international team, researchers from the Molecular Physics Department at the Fritz Haber Institute have revealed how atoms rearrange themselves before releasing low-energy electrons in a decay process initiated by X-ray irradiation. For the first time, they have gained detailed insights into the timing of the process—shedding light on related radiation damage mechanisms. Their research is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

High-energy radiation, for example in the X-ray range, can cause damage to our cells. This is because energetic radiation can excite atoms and molecules, which then often decay—meaning that biomolecules are destroyed and larger biological units can lose their function. There is a wide variety of such decay processes, and studying them is of great interest in order to better understand and avert radiation damage.

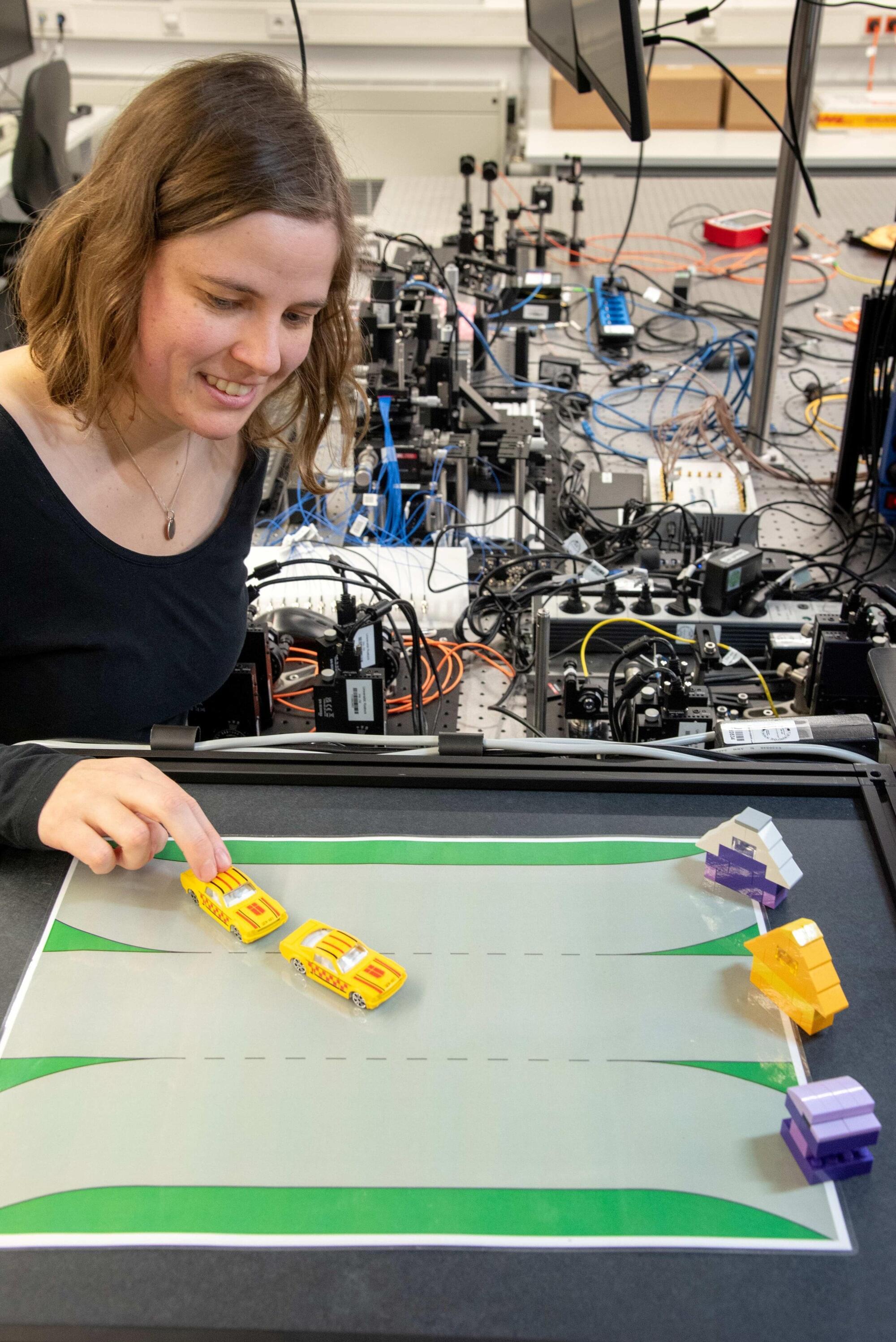

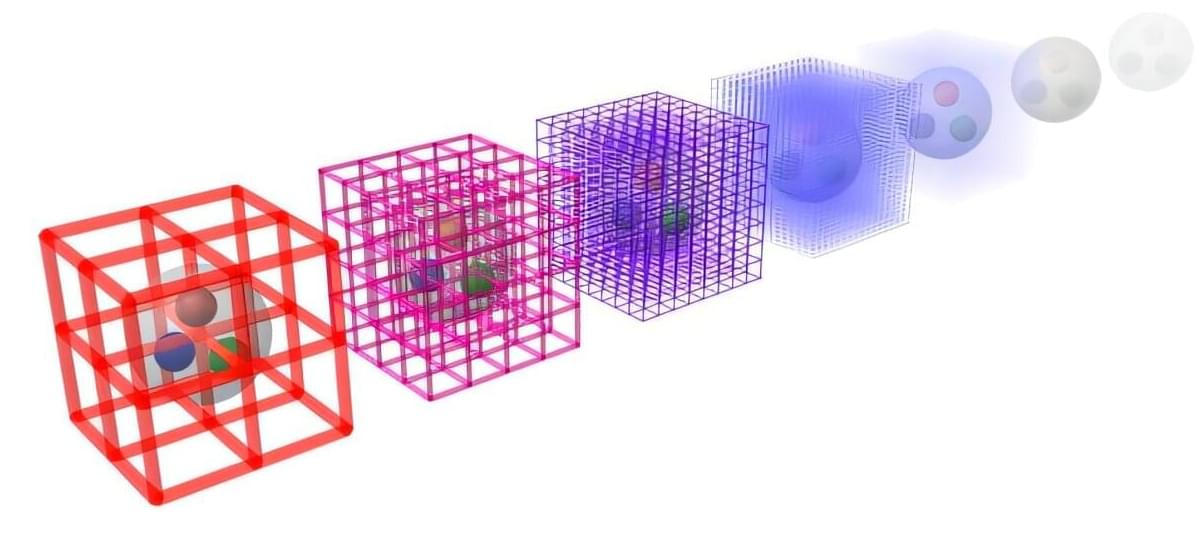

In the study, researchers from the Molecular Physics Department, together with international partners, investigated a radiation-induced decay process that plays a key role in radiation chemistry and biological damage processes: electron-transfer-mediated decay (ETMD). In this process, one atom is excited by irradiation. Afterward, this atom relaxes by stealing an electron from a neighbor, while the released energy ionizes yet another nearby atom.