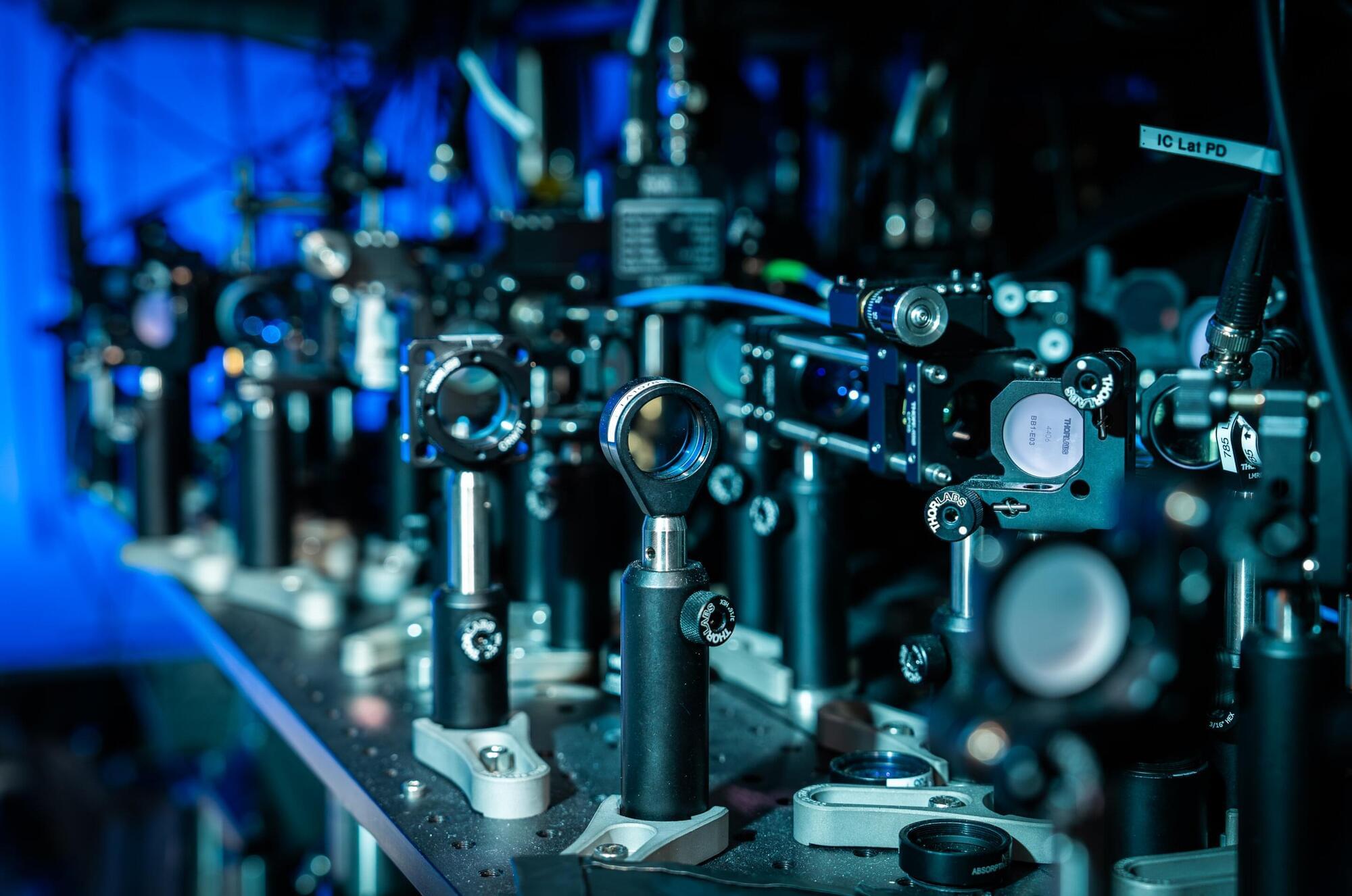

Researchers from Regensburg and Birmingham have overcome a fundamental limitation of optical microscopy. With the help of quantum mechanical effects, they succeeded for the first time in performing optical measurements with atomic resolution. Their work is published in the journal Nano Letters.

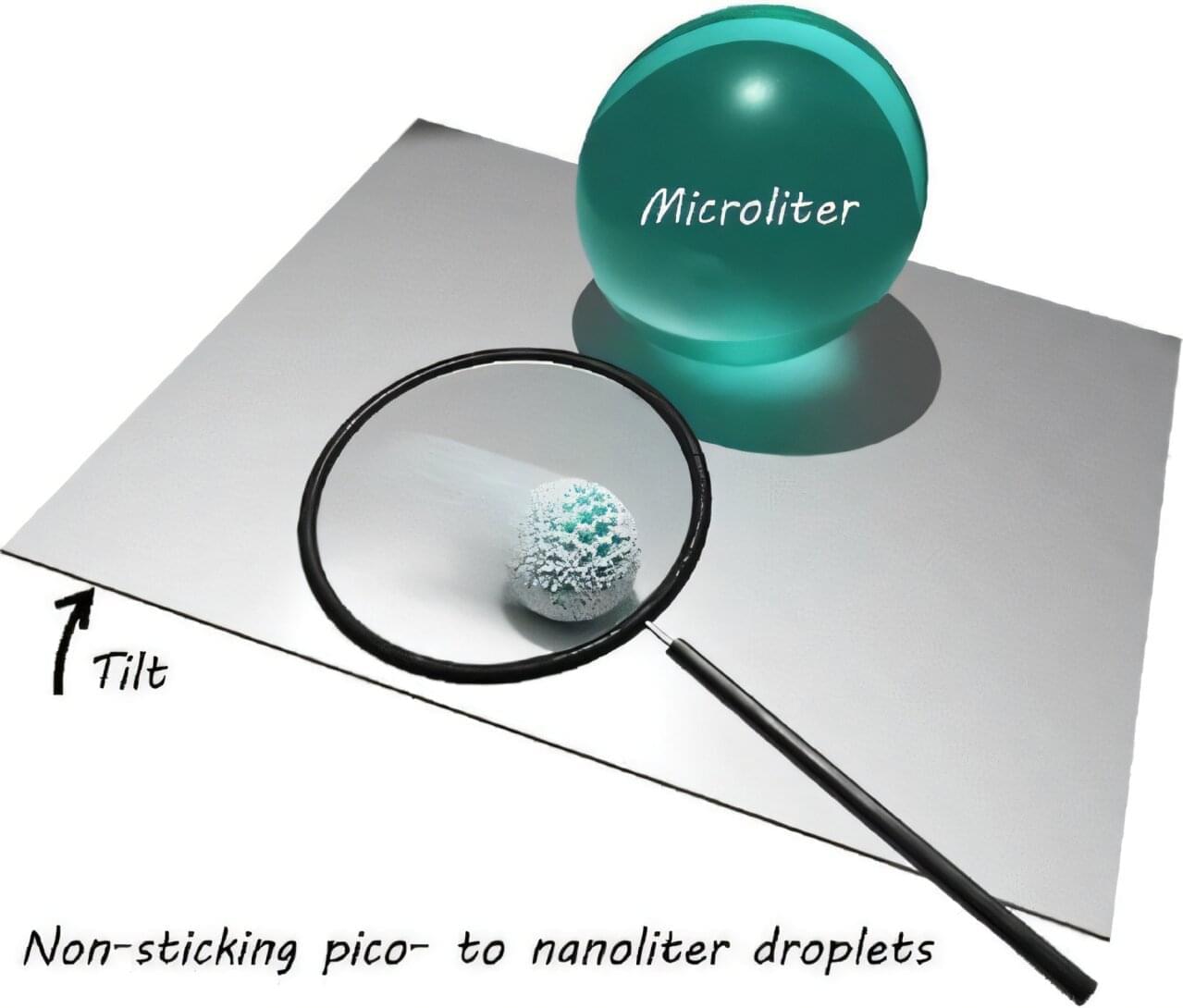

From smartphone cameras to space telescopes, the desire to see ever finer detail has driven technological progress. Yet as we probe smaller and smaller length scales, we encounter a fundamental boundary set by light itself. Because light behaves as a wave, it cannot be focused arbitrarily sharply due to an effect called diffraction. As a result, conventional optical microscopes are unable to resolve structures much smaller than the wavelength of light, placing the very building blocks of matter beyond direct optical observation.

Now, researchers at the Regensburg Center for Ultrafast Nanoscopy, together with colleagues at the University of Birmingham, have found a novel way to overcome this limitation. Using standard continuous-wave lasers, they have achieved optical measurements at distances comparable to the spacing between individual atoms.