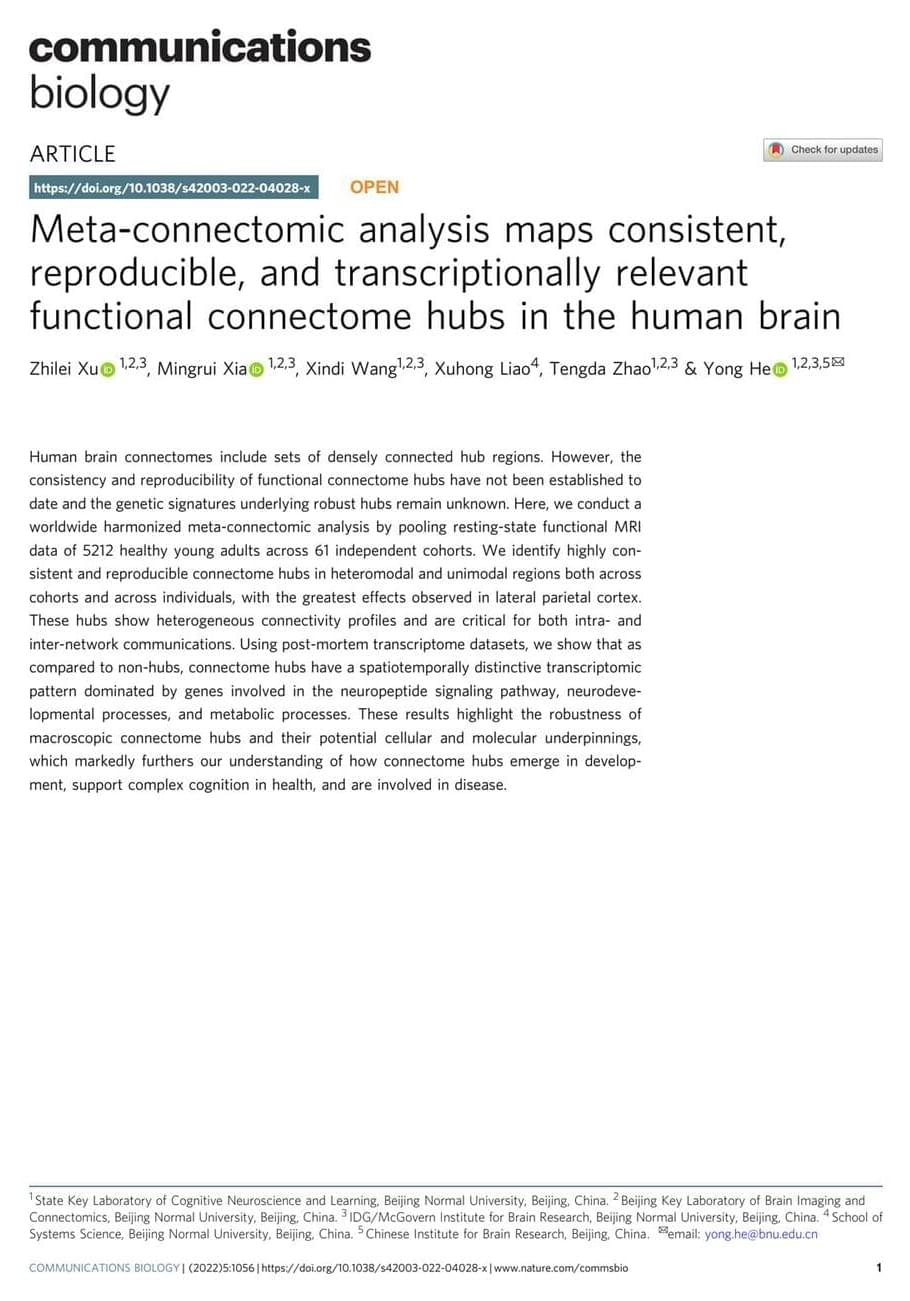

With anaesthetics and brain organoids, we are finally testing the idea that quantum effects explain consciousness – and the early results suggest this long-derided idea may have been misconstrued.

With anaesthetics and brain organoids, we are finally testing the idea that quantum effects explain consciousness – and the early results suggest this long-derided idea may have been misconstrued.

An exciting study reveals how exercise boosts brain power.

Summary: Recent research has revealed a significant link between exercise and improved cognitive performance, attributing this enhancement to increased dopamine levels. This discovery, involving sophisticated PET scans to monitor dopamine release in the brain during exercise, indicates that dopamine plays a vital role in boosting reaction times and overall brain function.

The study’s implications are far-reaching, suggesting potential therapeutic applications for conditions influenced by dopamine, like Parkinson’s disease and ADHD. The research underscores the importance of voluntary exercise for cognitive health, differentiating it from involuntary muscle stimulation.

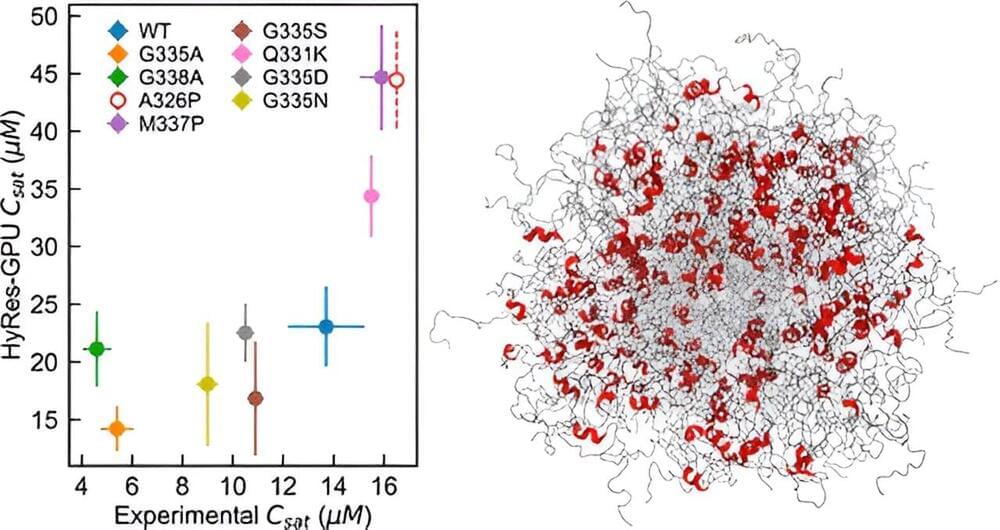

A University of Massachusetts Amherst team has made a major advance toward modeling and understanding how intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) undergo spontaneous phase separation, an important mechanism of subcellular organization that underlies numerous biological functions and human diseases.

IDPs play crucial roles in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders and infectious diseases. They make up about one-third of proteins that human bodies produce, and two-thirds of cancer-associated proteins contain large, disordered segments or domains. Identifying the hidden features crucial to the functioning and self-assembly of IDPs will help researchers understand what goes awry with these features when diseases occur.

In a paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, senior author Jianhan Chen, professor of chemistry, describes a novel way to simulate phase separations mediated by IDPs, an important process that has been difficult to study and describe.

According to a paper submitted for peer review on January 4th, 2024, Lethal Infection of Human ACE2-Transgenic Mice Caused by SARS-CoV-2-related Pangolin Coronavirus GX_P2V(short_3UTR), a new lab-created coronavirus has the potential to kill 100% of those infected with the virus within 8 days of infection.

The mice were genetically modified to express the human ACE2 receptor. This is the receptor responsible for allowing coronavirus to gain cellular entry. The lab infected mice with a coronavirus engineered from a strain found in pangolins. Pangolins are medium-sized animals growing to 12 — 30 inches in length and have the appearance of a scale-plated anteater.

Researchers monitored the mice for signs of infection by recording body weight, taking tissue samples, and monitoring for other symptoms. By the third day post-infection, tissue samples from the infected mice had a significant amount of viral RNA in the brain, eye, lung, and nasal tissue.

👁️ 🧠 🔬

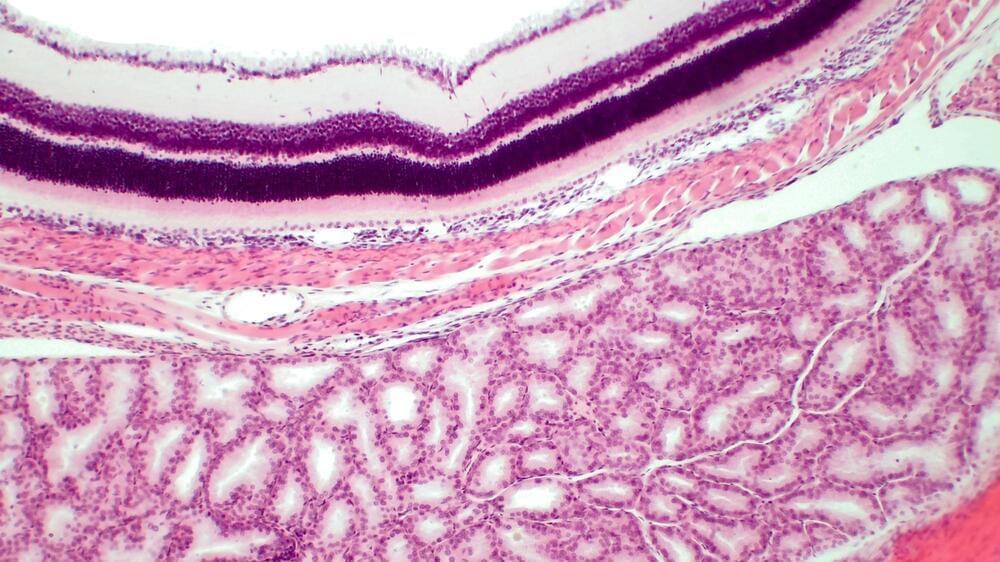

A recent study published in the journal Npj Parkinson’s Disease investigated whether increased thinning rate in the parafoveal ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (pfGCIPL) and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) indicates the progression of the Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Study: Association of retinal neurodegeneration with the progression of cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. Image Credit: BioFoto / Shutterstock

Background

Retinal changes are robustly associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD. The changes in retinal layer thickness can be assessed using high-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT). Among different retinal layers, the ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) can be used as a biomarker to determine cognitive decline and neurodegeneration.

Gallery QI Opening Event: Distributed Consciousness – Memo Akten – January 25, 2024 – 5 p.m. Join Gallery QI for the opening event of Distributed Consciousne…

“Permutation City” by Greg Egan explores the nature of reality, consciousness, and existence. Set in a future where people can upload their consciousness into virtual realities, known as “Autoverse.” A software engineer, René Barjavel, becomes embroiled in a complex and mind-bending exploration of identity and the nature of existence as he grapples with the implications of living in a world where reality itself may be a simulation.