The human brain is a fascinating and complex organ that supports numerous sophisticated behaviors and abilities that are observed in no other animal species. For centuries, scientists have been trying to understand what is so unique about the human brain and how it develops over the human lifespan.

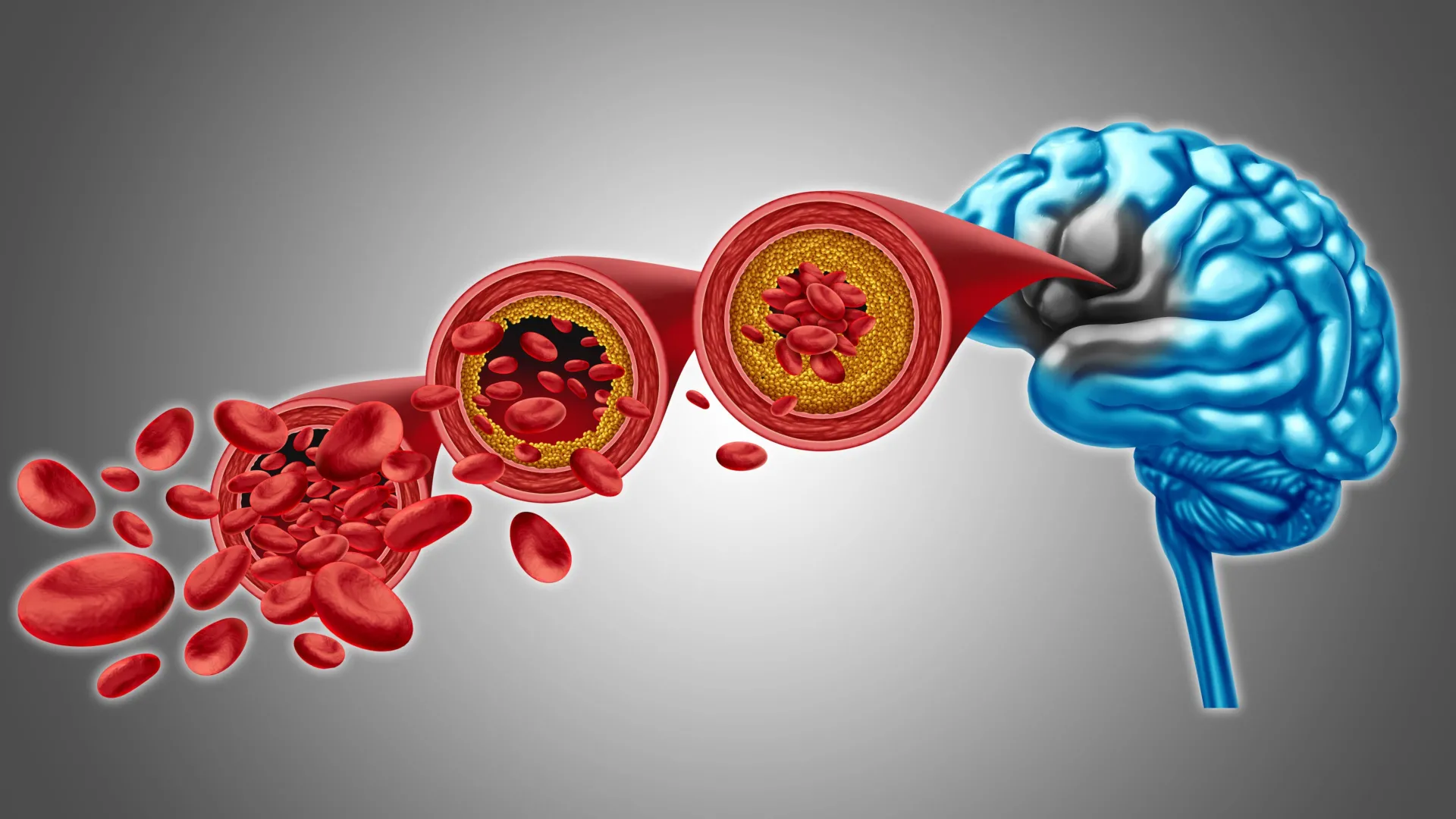

Recent technological and experimental advances have opened new avenues for neuroscience research, which in turn has led to the creation of increasingly detailed descriptions of the brain and its underlying processes. Collectively, these efforts are helping to shed new light on the underpinnings of various neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders.

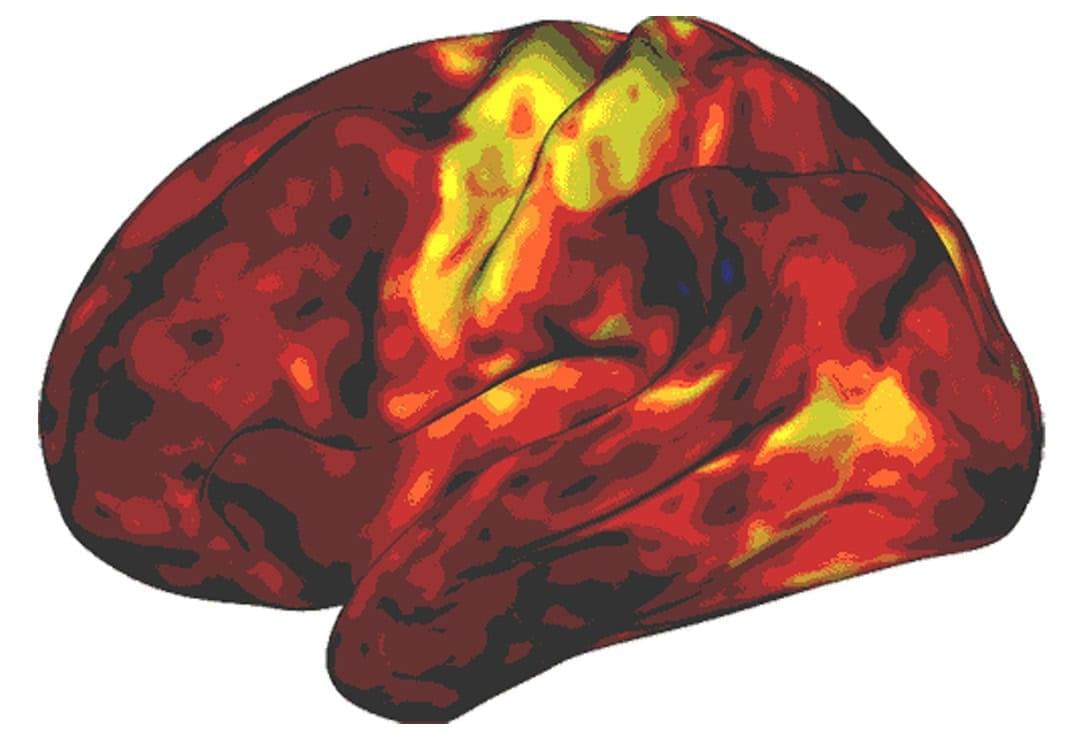

Researchers at Beijing Normal University, the Changping Laboratory and other institutes have recently set out to study both the human and macaque brain, comparing their development over time using various genetic and molecular analysis tools. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, highlights some key differences between the two species, with the human pre-frontal cortex (PFC) developing slower than the macaque PFC.