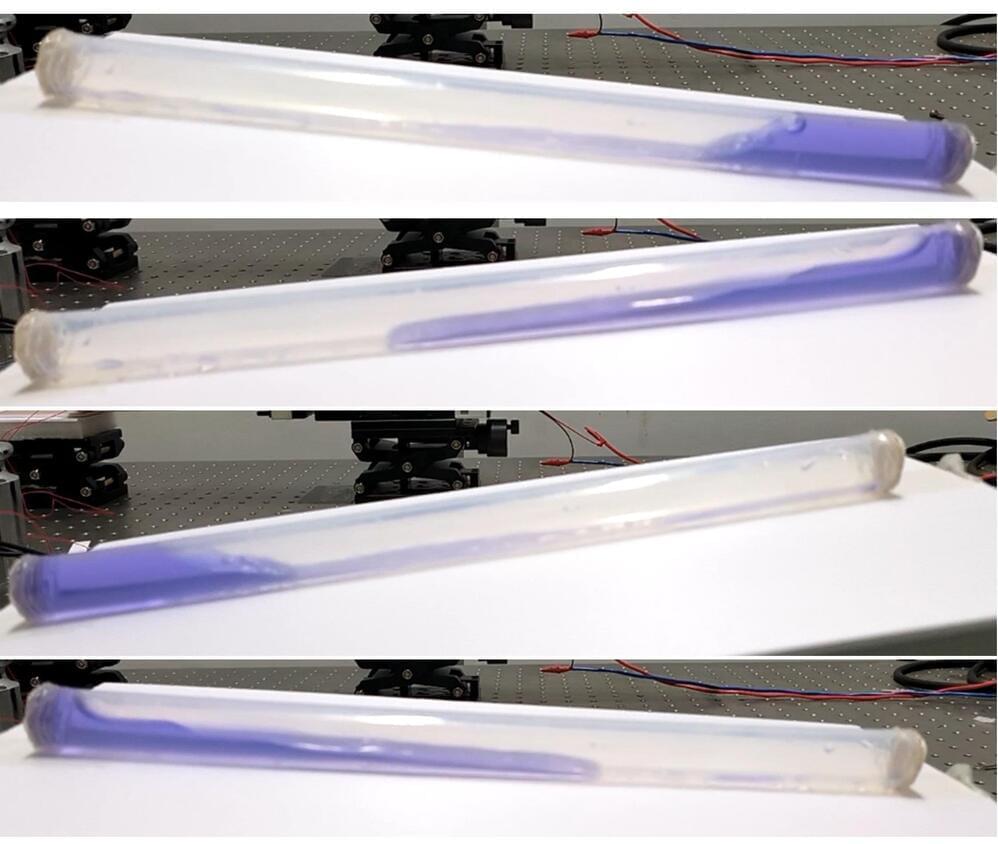

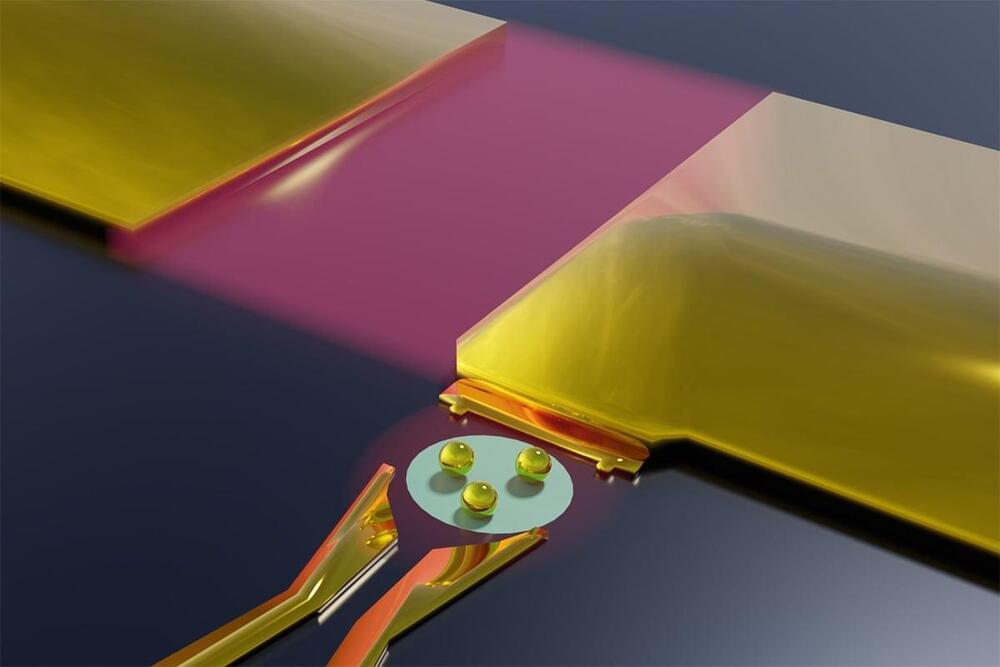

As any surfer will tell you, waves pack a powerful punch. We’re now making strides toward harnessing the ocean’s relentless movements for energy, thanks to advancements in “blue energy” technology. In a study published in ACS Energy Letters, researchers discovered that by moving the electrode from the middle to the end of a liquid-filled tube—where the water’s impact is strongest—they significantly boosted the efficiency of wave energy collection.

The tube-shaped wave-energy harvesting device improved upon by the researchers is called a liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG). The TENG converts mechanical energy into electricity as water sloshes back and forth against the inside of the tube. One reason these devices aren’t yet practical for large-scale applications is their low energy output. Guozhang Dai, Kai Yin, Junliang Yan, and colleagues aimed to increase a liquid-solid TENG’s energy harvesting ability by optimizing the location of the energy-collecting electrode.