Topological materials could usher in a new age of electronics, but scientists are still discovering surprising aspects of their quantum nature.

A UCLA-led, multi-institution research team has discovered a metallic material with the highest thermal conductivity measured among metals, challenging long-standing assumptions about the limits of heat transport in metallic materials.

Published in Science, the study was led by Yongjie Hu, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. The team reported that metallic theta-phase tantalum nitride conducts heat nearly three times more efficiently than copper or silver, the best conventional heat-conducting metals.

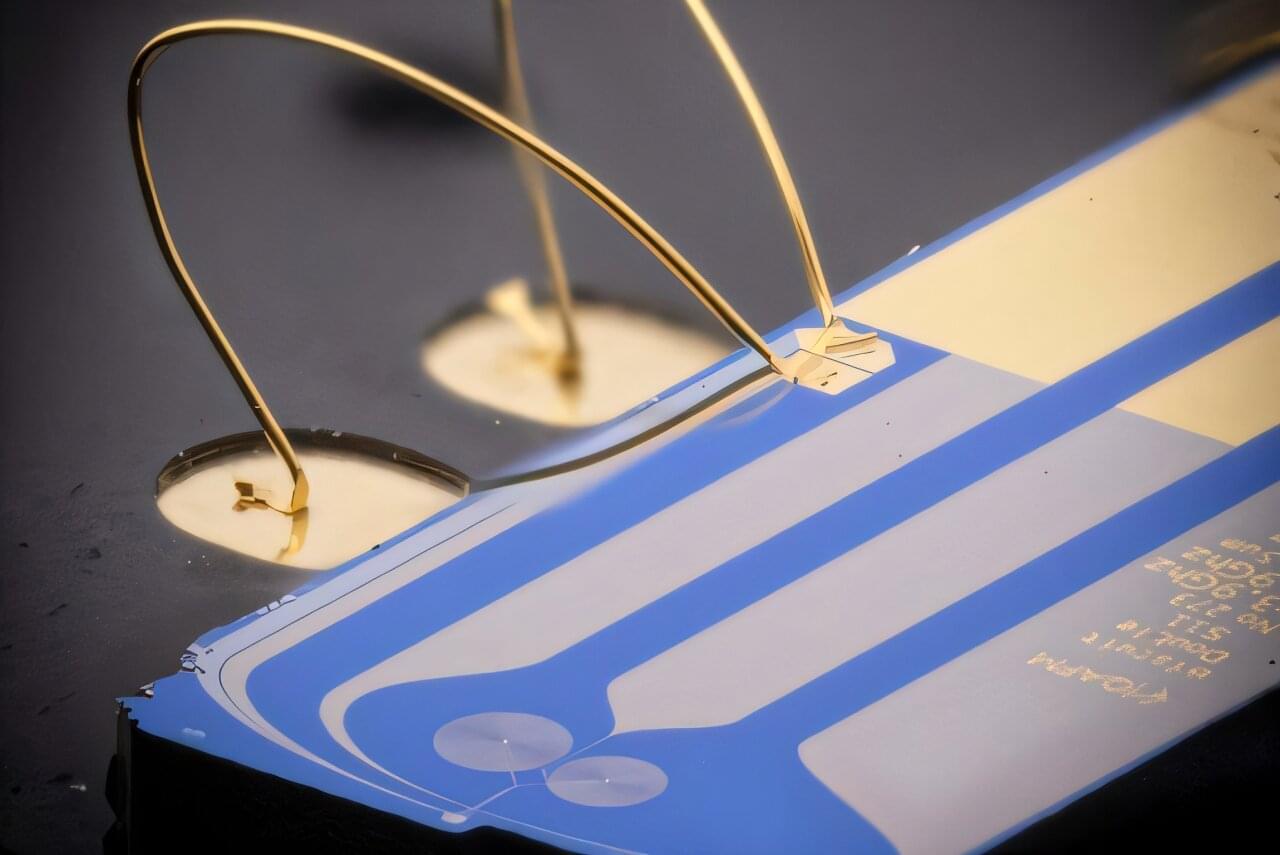

Nanomechanical systems developed at TU Wien have now reached a level of precision and miniaturization that will allow them to be used in ultra-high-resolution atomic force microscopes in the future. Their new findings are published in the journal Advanced Materials Technologies.

A major leap in measurement technology begins with a tiny gap of just 32 nanometers. This is the distance between a movable aluminum membrane and a fixed electrode, together forming an extremely compact parallel-plate capacitor—a new world record. This structure is intended for use in highly precise sensors, such as those required for atomic force microscopy.

But this world record is more than just an impressive feat of miniaturization—it is part of a broader strategy. TU Wien is developing various hardware platforms to make quantum sensing easier to use, more robust, and more versatile. In conventional optomechanical experiments, the motion of tiny mechanical structures is read out using light. However, optical setups are delicate, complex, and difficult to integrate into compact, portable systems. TU Wien therefore relies on other types of oscillations that are better suited for compact sensors.

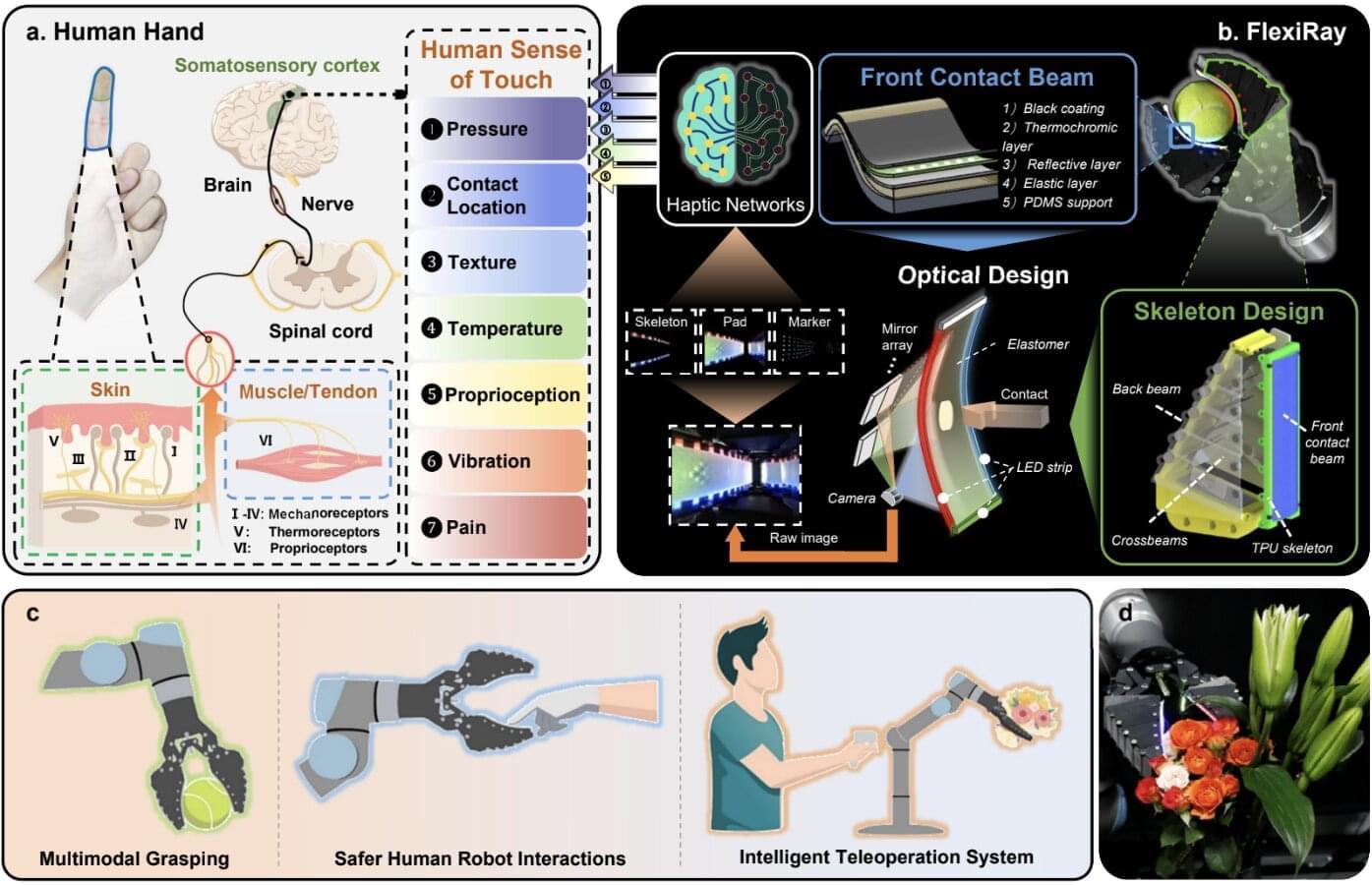

To reliably complete household chores, assemble products and tackle other manual tasks, robots should be able to adapt their manipulation strategies based on the objects they are working with, similarly to how humans leverage information they gain via the sense of touch. While humans attain tactile information via nerves in their skin and muscles, robots rely on sensors, devices that sense their surroundings and pick up specific physical signals.

Most robotic hands and grippers developed so far rely on visual-tactile sensors, systems that use small cameras to capture images, while also picking up surface deformations resulting from contact with specific objects.

A key limitation of these sensors is that they need to be made of stiff materials, to ensure that the cameras capture high-quality images. This reduces the overall flexibility of robots that rely on the sensors, making it harder for them to handle fragile and unevenly shaped objects.

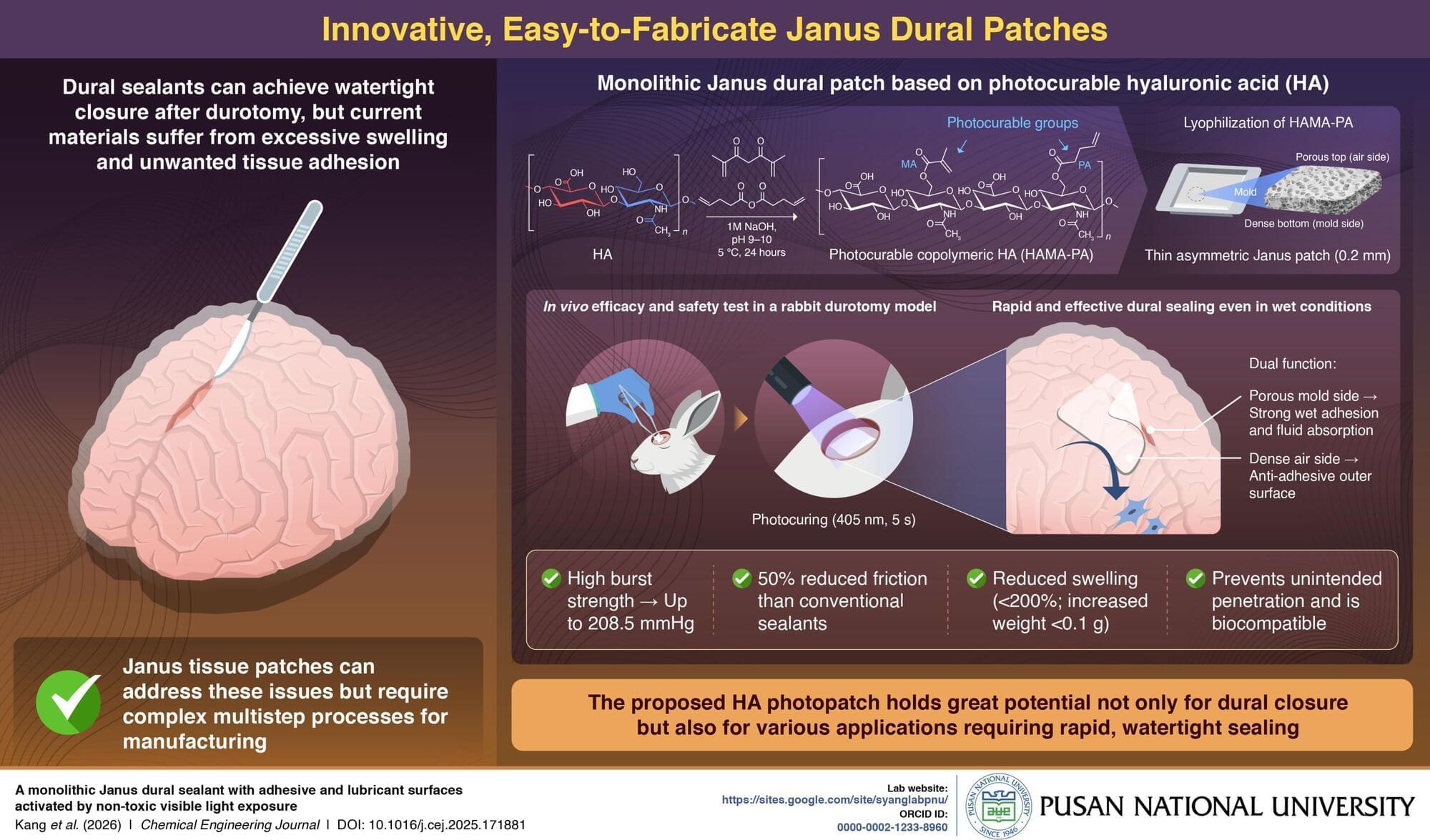

Durotomy is a common neurosurgical complication involving a tear in the dura mater, the protective membrane surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Damage can cause cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, leading to delayed healing, headaches, and infection, making a reliable watertight dural closure essential.

Tissue adhesives are increasingly being explored as alternatives to suturing for dural closure because they offer simpler and faster application. However, many existing glue-based sealants suffer from excessive swelling, leading to mass effect and unwanted tissue adhesion, which can lead to postoperative complications.

To address these limitations, researchers have investigated Janus tissue patches, which feature two distinct surfaces—one that adheres strongly to tissue and another that prevents unwanted adhesion. Unfortunately, most existing Janus patches rely on multiple materials and complex, multi-step fabrication processes, limiting their practical use.

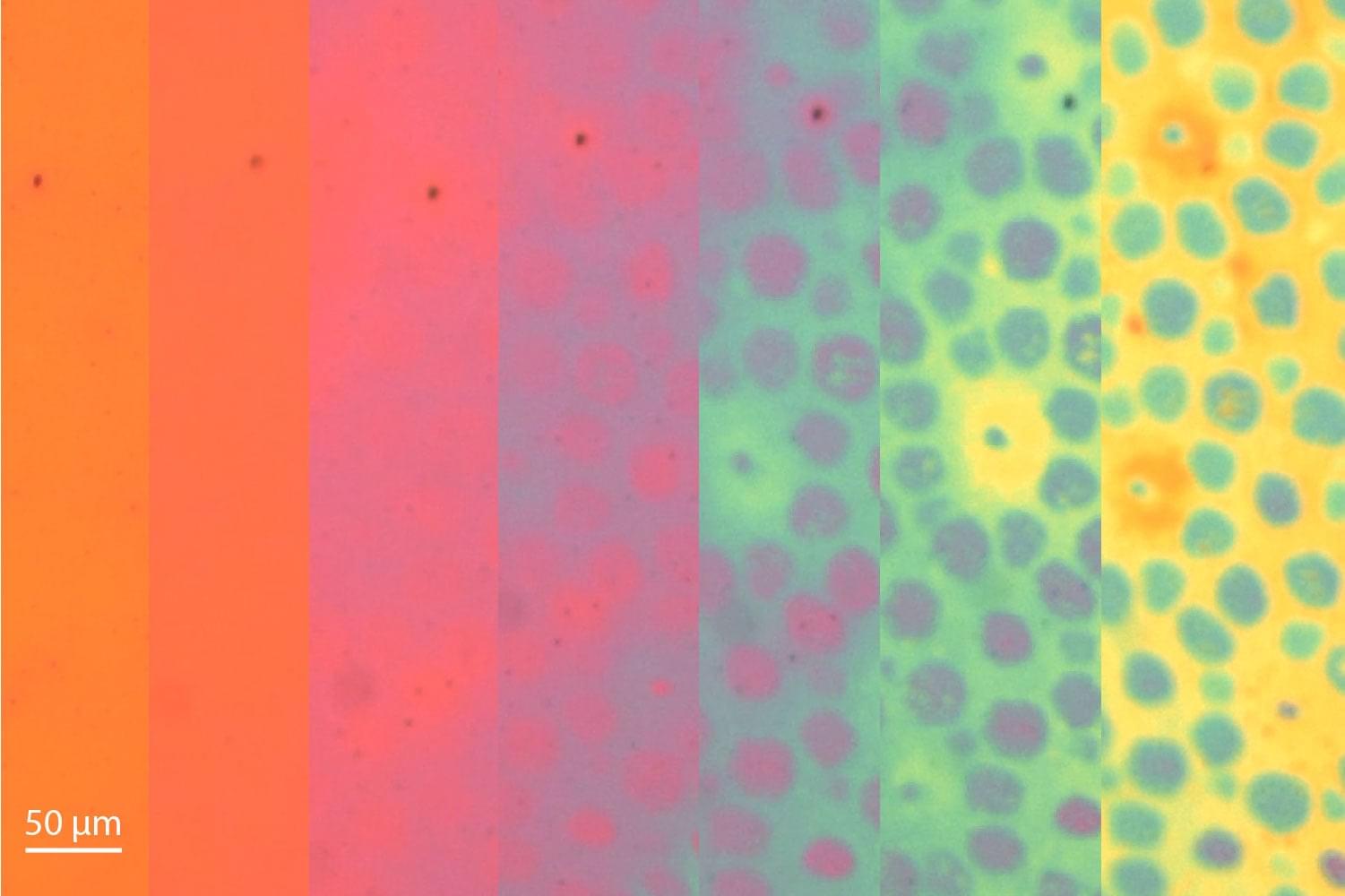

Researchers at the Department of Materials Science and Engineering within The Grainger College of Engineering have identified the first detailed physical mechanism explaining how magnetic fields slow the movement of carbon atoms inside iron. The study, published in Physical Review Letters, sheds new light on the role carbon plays in shaping the internal grain structure of steel.

Steel, which is made from iron and carbon, is among the most widely used construction materials worldwide. Producing steel with specific internal structures typically requires extreme heat, making the process highly energy intensive.

Decades ago, researchers observed that exposing certain steels to magnetic fields during heat treatment led to improved performance, but the explanations offered at the time remained largely theoretical. Pinpointing the underlying cause of this effect could give engineers more precise control over heat treatment, leading to more efficient processing and lower energy demands.

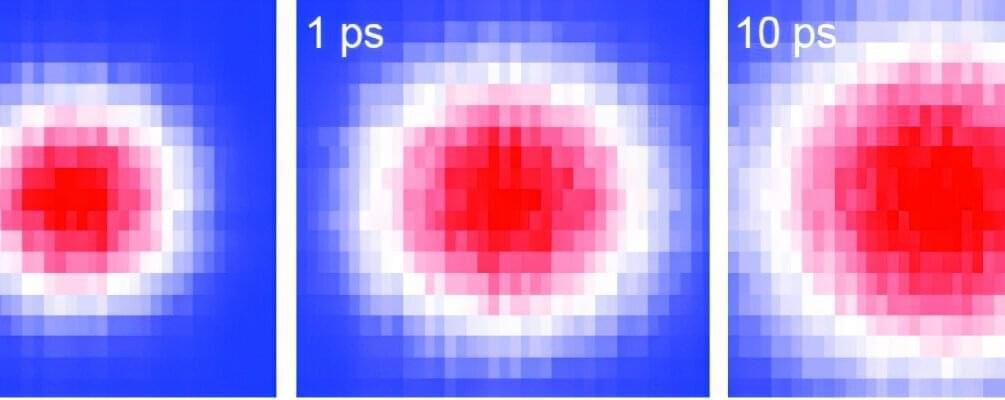

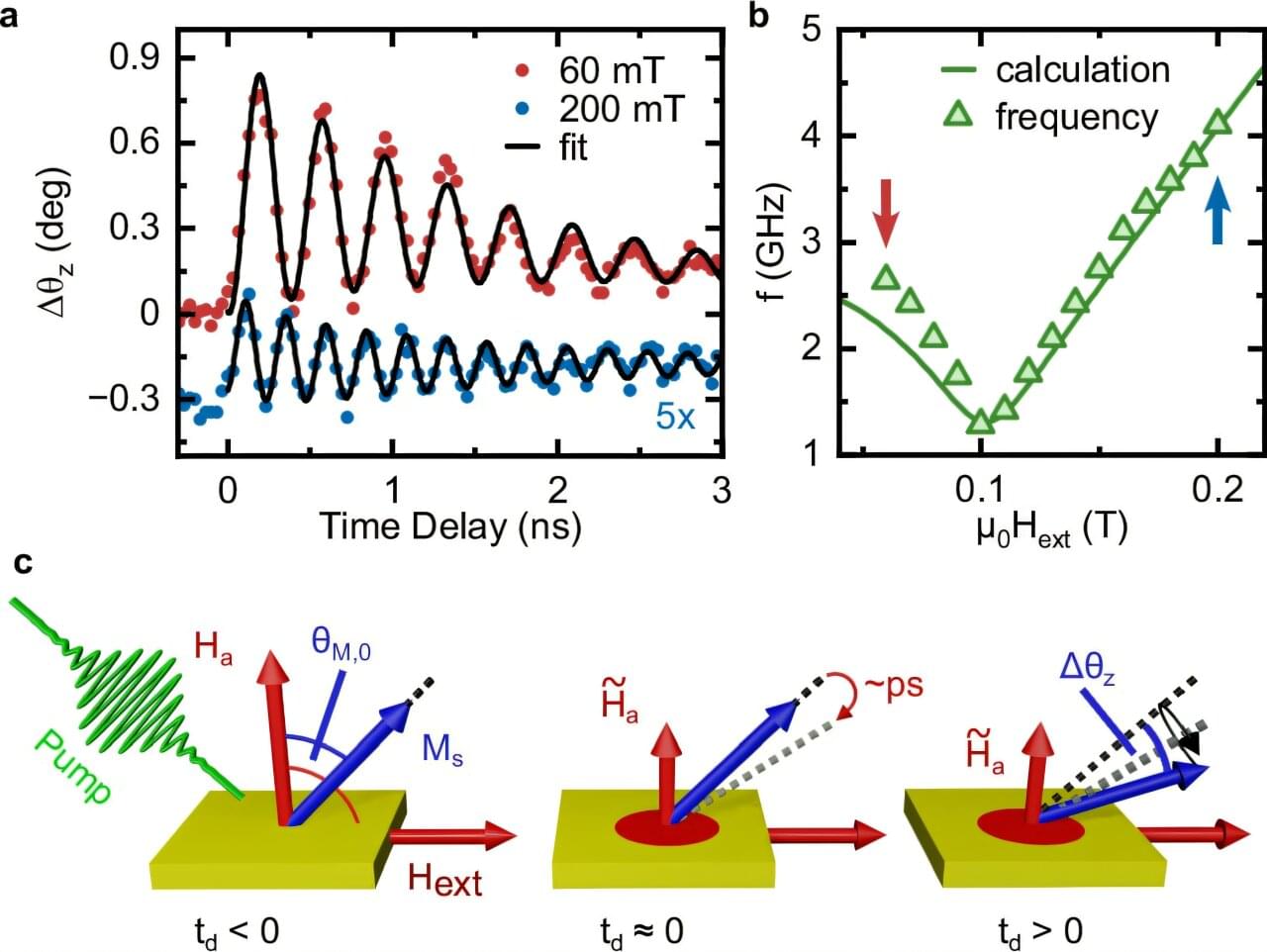

Physicist Davide Bossini from the University of Konstanz has recently demonstrated how to change the frequency of the collective magnetic oscillations of a material by up to 40%—using commercially available devices at room temperature.

“We now have a full picture,” Bossini says. For years, the physicist from the University of Konstanz has studied how to use light to control the collective magnetic oscillations of a material—known as magnons. In the summer of 2025, he was finally able to show how to change the “magnetic DNA” of a material via the interaction between light and magnons.

He now demonstrates how the frequency of oscillations can be controlled quasi instantly and on demand by means of a weak magnetic field and intense laser pulses. In this way, he can increase or decrease frequencies by up to 40%. The effect is due to the interaction of the optical excitation, magnetic anisotropy (directional dependence) and the external magnetic field.