How common are Earth-like planets in the universe? When I started working on supernova explosions, I never imagined that my research would eventually lead me to ask a question about the origin of Earth-like planets. Yet that is exactly where it brought me.

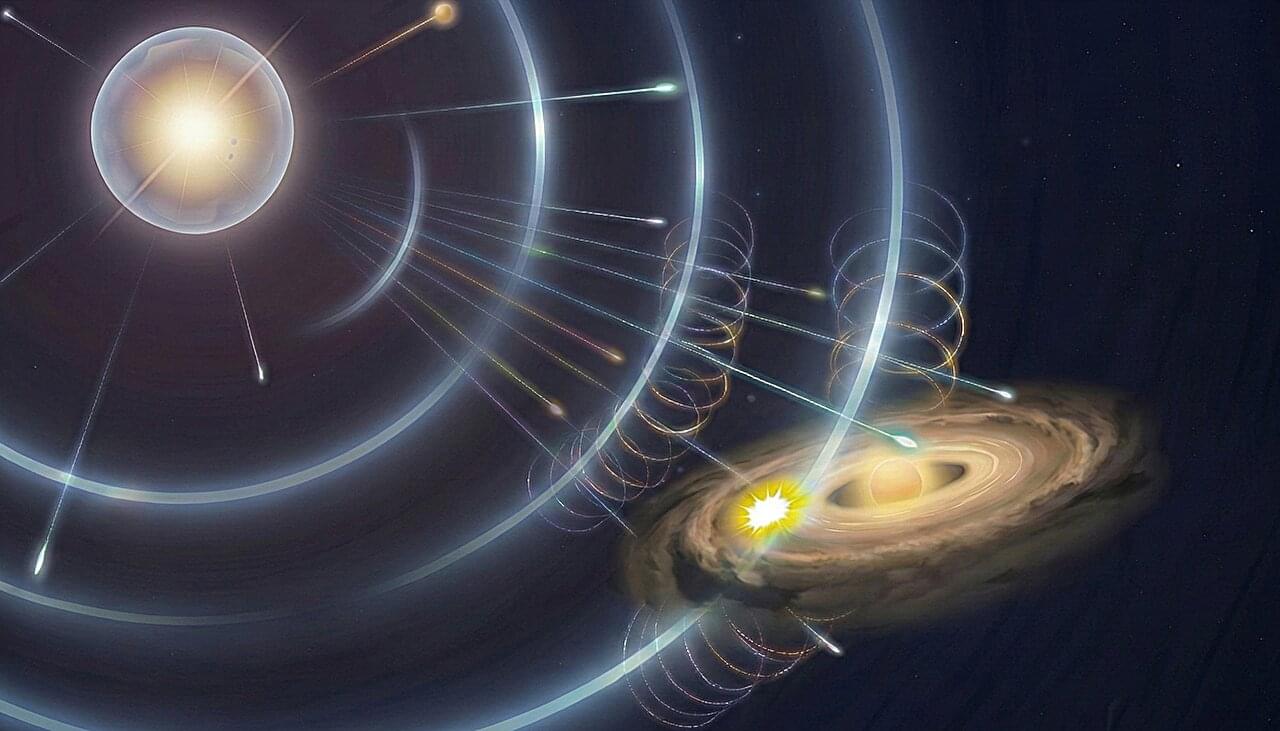

For decades, planetary scientists have believed that the early solar system was enriched with short-lived radioactive elements—such as aluminum-26—by a nearby supernova. These radioactive elements played a crucial role in forming water-depleted rocky planets such as Earth. Their decay heated young planetesimals, causing them to lose much of their originally accreted water and other volatile materials.

There was just one problem that kept bothering me.