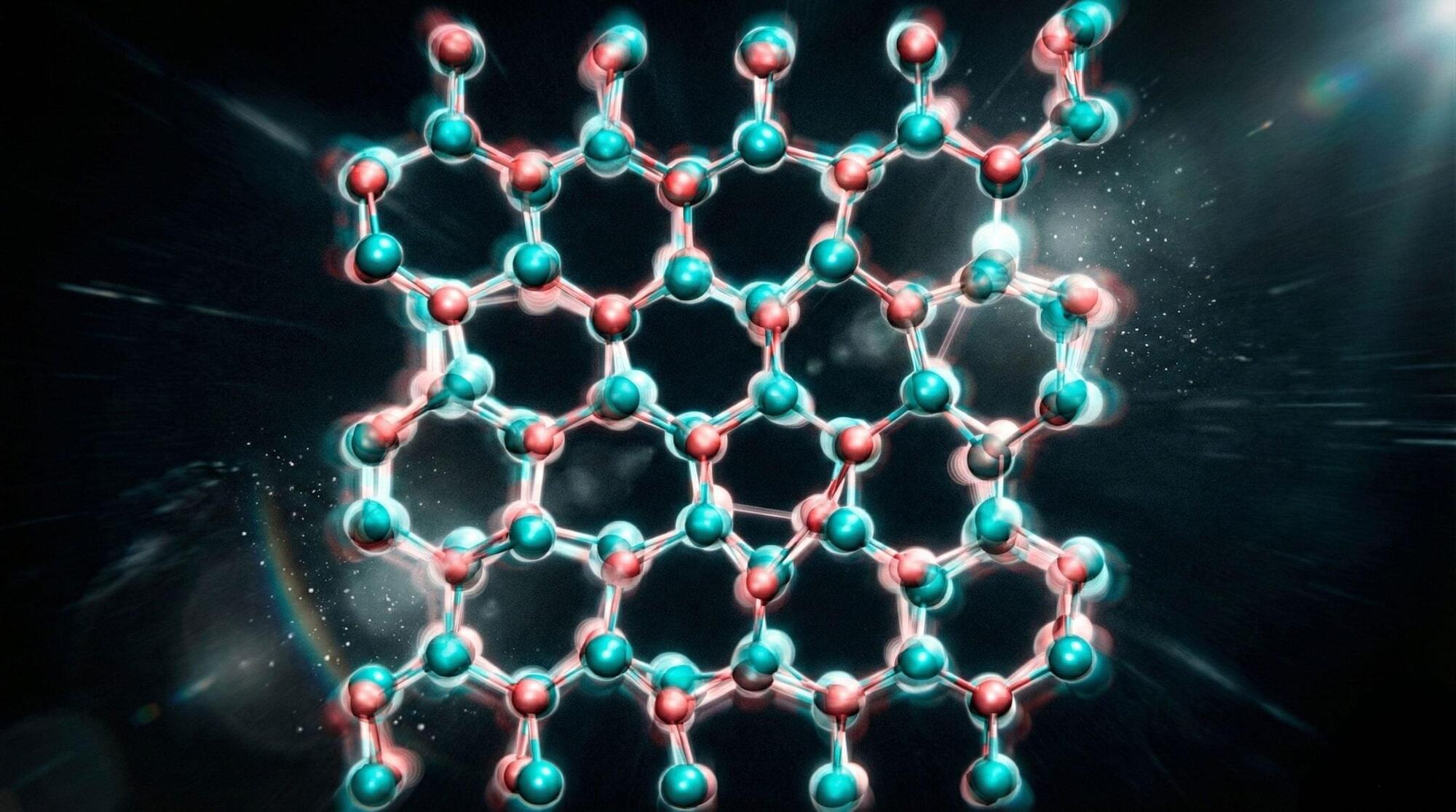

Step inside the strange world of a superfluid, a liquid that can flow endlessly without friction, defying the common-sense rules we experience every day, where water pours, syrup sticks and coffee swirls and slows under the effect of viscosity. In these extraordinary fluids, motion often organizes itself into quantized vortices: tiny, long-lived whirlpools that act as the fundamental building blocks of superfluid flow.

An international study conducted at the European Laboratory for Non-Linear Spectroscopy (LENS), involving researchers from CNR-INO, the Universities of Florence, Bologna, Trieste, Augsburg, and the Warsaw University of Technology, has embarked on this journey by investigating the dynamics of vortices within strongly interacting superfluids, uncovering the fundamental mechanisms that govern their behavior.

Using ultracold atomic gases, the scientists open a unique window into this exotic realm, recreating conditions similar to those found in superfluid helium-3, the interiors of neutron stars, and superconductors.