Researchers engineered a quantum material with superconducting and topological traits, opening the door to ultra-efficient electronics.

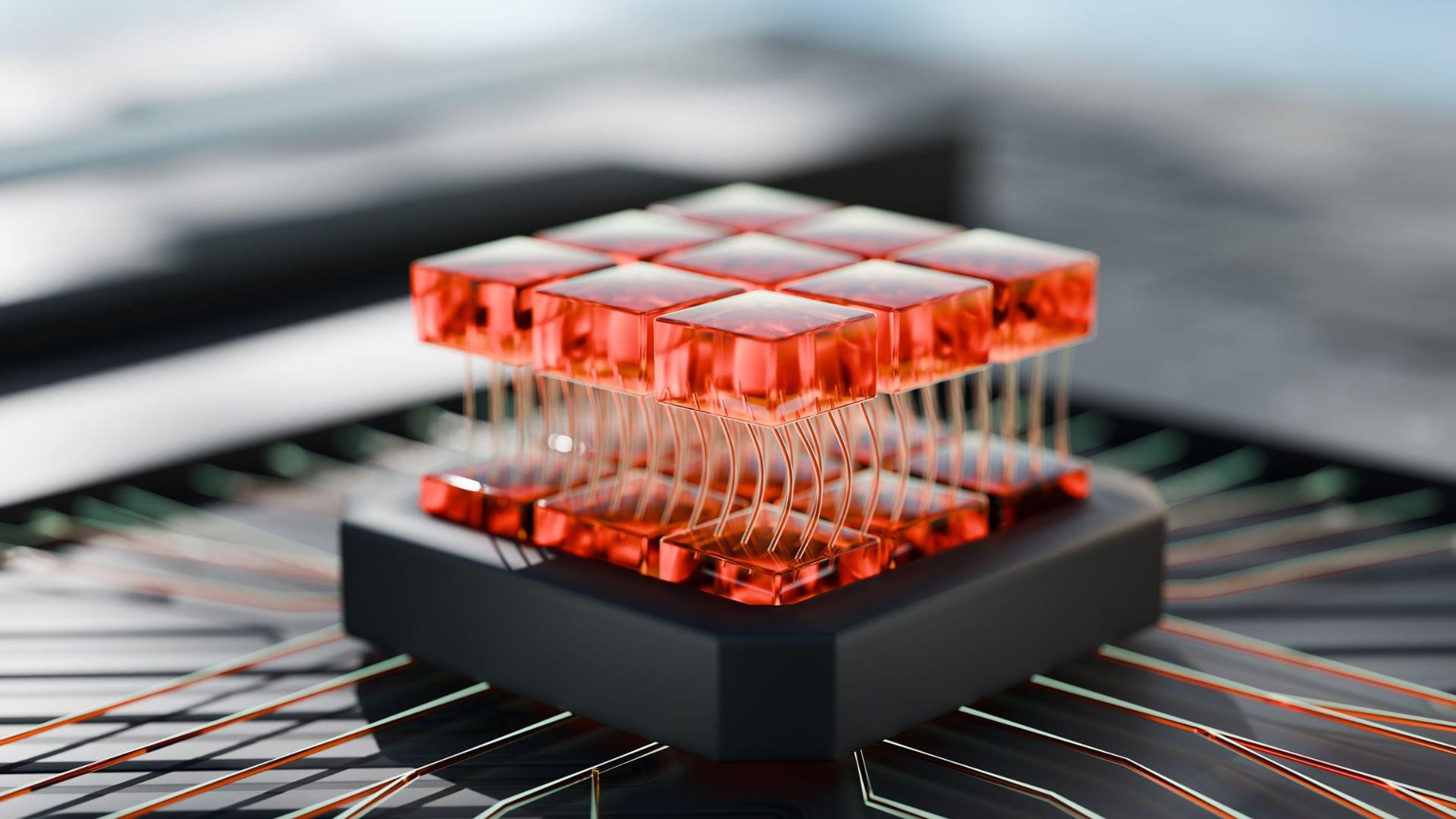

As the digital world demands greater data storage and faster access times, magnetic memory technologies have emerged as a promising frontier. However, conventional magnetic memory devices have an inherent limitation: they use electric currents to generate the magnetic fields necessary to reverse their stored magnetization, leading to energy losses in the form of heat.

This inefficiency has pushed researchers to explore approaches that could further reduce power consumption in magnetic memories while maintaining or even enhancing their performance.

Multiferroic materials, which exhibit both ferroelectric and ferromagnetic properties, have long been considered potential game changers for next-generation memory devices.

Five years after introducing see-through wood building material, researchers in Sweden have taken it to another level. They found a way to make their composite 100 percent renewable – and more translucent – by infusing wood with a clear bio-plastic made from citrus fruit.

Since it was first introduced in 2016, transparent wood has been developed by researchers at KTH Royal Institute of Technology as one of the most innovative new structural materials for building construction. It lets natural light through and.

The key to making wood into a transparent composite material is to strip out its lignin, the major light-absorbing component in wood. But the empty pores left behind by the absence of lignin need to be filled with something that restores the wood’s strength and allows light to permeate.

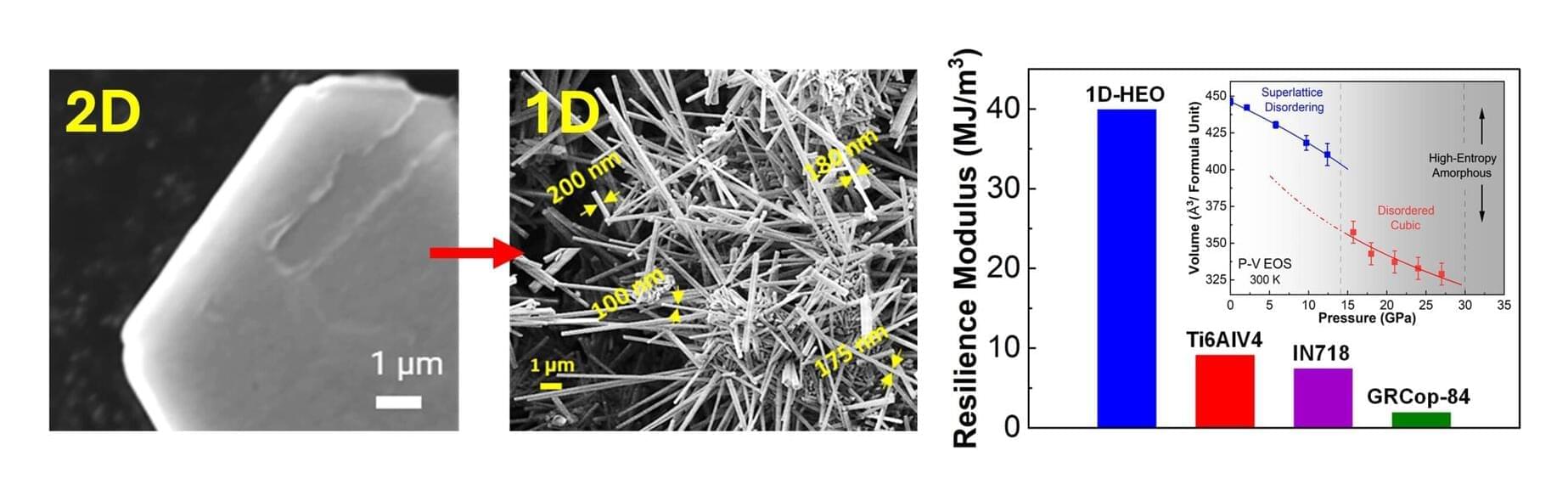

An SMU-led research team has developed a more cost-effective, energy-efficient material called high-entropy oxide (HEO) nanoribbons that can resist heat, corrosion and other harsh conditions better than current materials.

These HEO nanoribbons— featured in the journal Science —can be especially useful in fields like aerospace, energy, and electronics, where materials need to perform well in extreme conditions.

And unlike high entropy materials that have been created in the past, the nanoribbons that SMU’s Amin Salehi-Khojin and his team developed can be 3D-printed or spray-coated at room temperature for manufacturing components or coating surfaces. This makes them more energy-efficient and cost-effective than traditional high-entropy materials, which typically exist as bulk structures and require high-temperature casting.

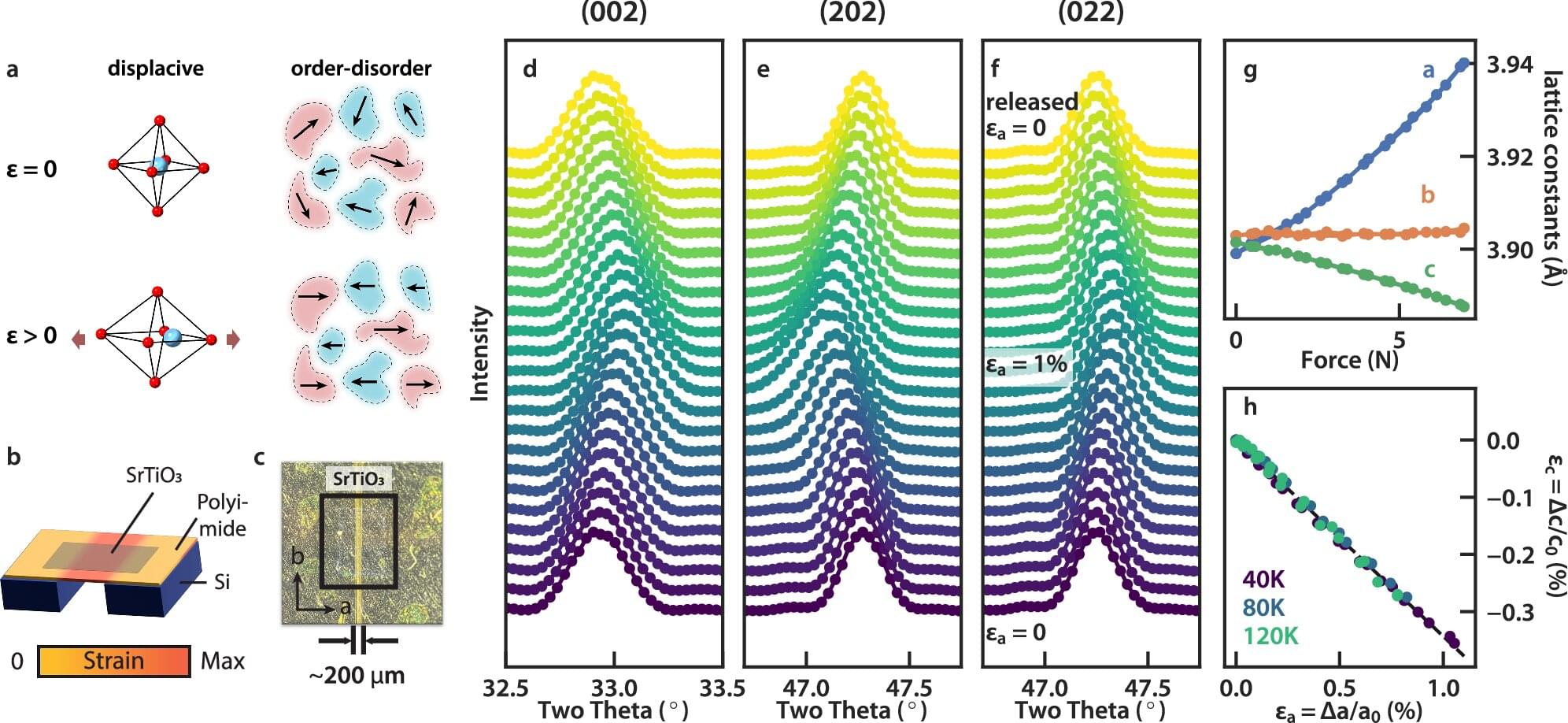

Strontium titanate was once used as a diamond substitute in jewelry before less fragile alternatives emerged in the 1970s. Now, researchers have explored some of its more unusual properties, which might someday be useful in quantum materials and microelectronics applications.

Writing in the journal Nature Communications, the team explains how they built an extremely thin, flexible strontium titanate membrane and stretched it, in the process turning on what’s known as a ferroelectric state. In that state, the material generates its own electric field, somewhat similar to how a permanent magnet generates its own magnetic field.

“We applied strain to tune the membrane to a ferroelectric or non-ferroelectric state reversibly and repeatedly,” said Wei-Sheng Lee, a lead scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and a principal investigator at the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES), a joint SLAC-Stanford institute. “This allowed quantitative characterizations of this transition in strontium titanate with unprecedented details.”

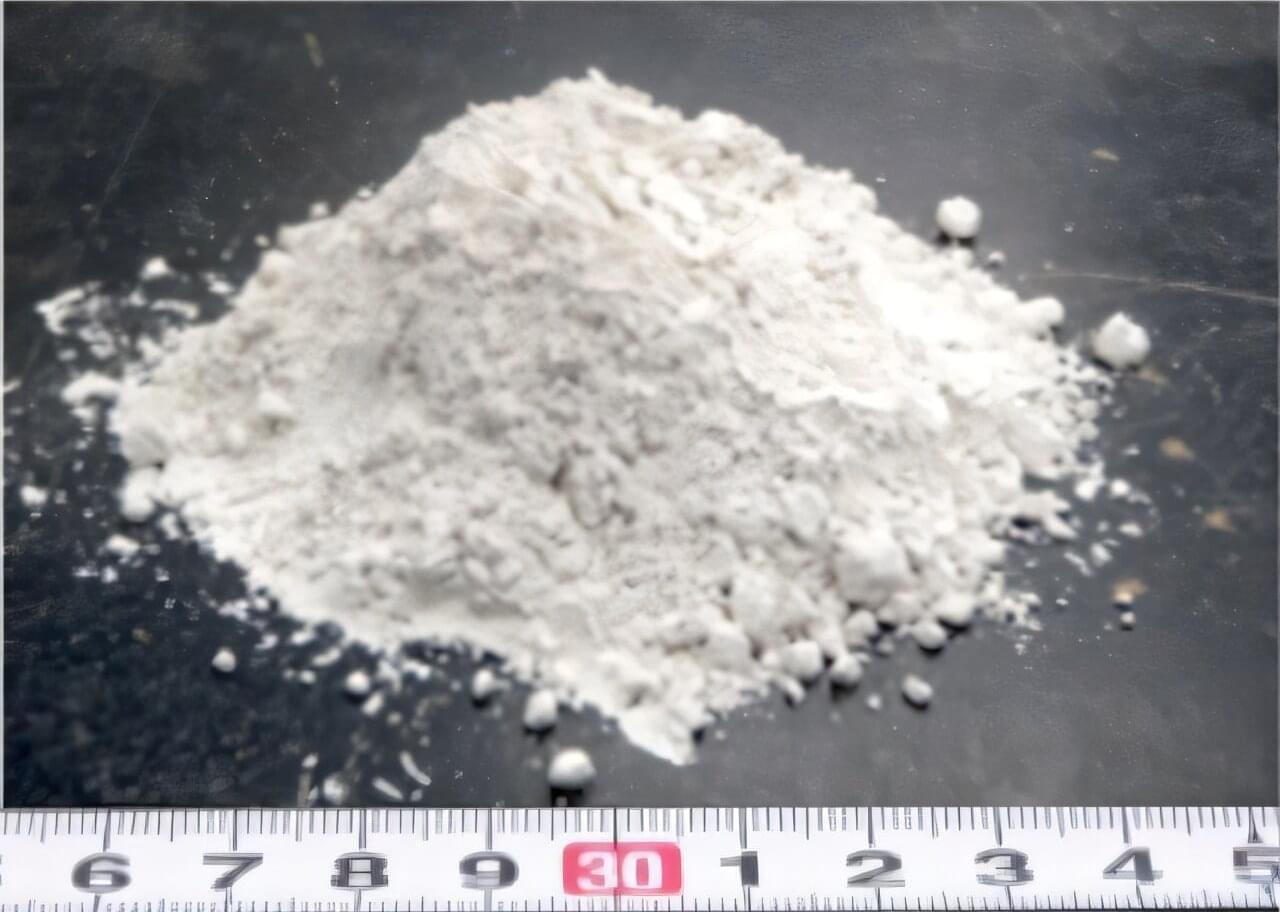

With global population growth accelerating urban expansion, construction activity has reached unprecedented levels—placing immense pressure on both natural resources as well as the environment. A cornerstone of modern-day infrastructure, Ordinary Portland Cement remains the most effective and commonly used soil solidifier despite contributing substantially to global carbon emissions.

At the same time, construction waste continues to accumulate in landfills. Addressing both the environmental burden of cement use and the inefficiencies of industrial waste disposal has become an urgent priority.

To tackle these interconnected challenges, scientists from Japan, led by Professor Shinya Inazumi, from the College of Engineering, Shibaura Institute of Technology (SIT), Japan, present a sustainable alternative: a high-performance geopolymer-based soil solidifier developed from Siding Cut Powder (SCP), a construction waste byproduct, and earth silica (ES), sourced from recycled glass.

Solid-state batteries are seen as a game-changer for the future of energy storage. They can hold more power and are safer because they don’t rely on flammable materials like today’s lithium-ion batteries. Now, researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and TUMint. Energy Research have made a major breakthrough that could bring this future closer.

They have created a new material made from lithium, antimony, and a small amount of scandium. This material allows lithium ions to move more than 30 percent faster than any known alternative. That means record-breaking conductivity, which could lead to faster charging and more efficient batteries.

Led by Professor Thomas F. Fässler, the team discovered that swapping some of the lithium atoms for scandium atoms changes the structure of the material. This creates specific gaps, so-called vacancies, in the crystal lattice of the conductor material. These gaps help the lithium ions to move more easily and faster, resulting in a new world record for ion conductivity.

Bike locks or lightweight armour that cannot be cut by any tool, even angle grinders or high-pressure water jets, sound like an unattainable dream.

They could be remarkably close, however, thanks to a new ‘non-cuttable’ material developed by engineers at Durham University and the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany.

Researchers took inspiration from shells to create the strong and lightweight material, named Proteus after the shape-changing mythical god. Another unusual inspiration was grapefruit, which have very high impact resistance – when dropped from a height, for example – with very lightweight peel.

The material resists cutting by turning the force of a cutting tool back on itself. It is made of ceramic spheres encased in a cellular aluminium structure, similar to the organic tiles interlinked by biopolymers in abalone sea creatures.

Cookies are used to store and retrieve information from your browser. It may be about you or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect, but also to tailor your experience on this and other sites.

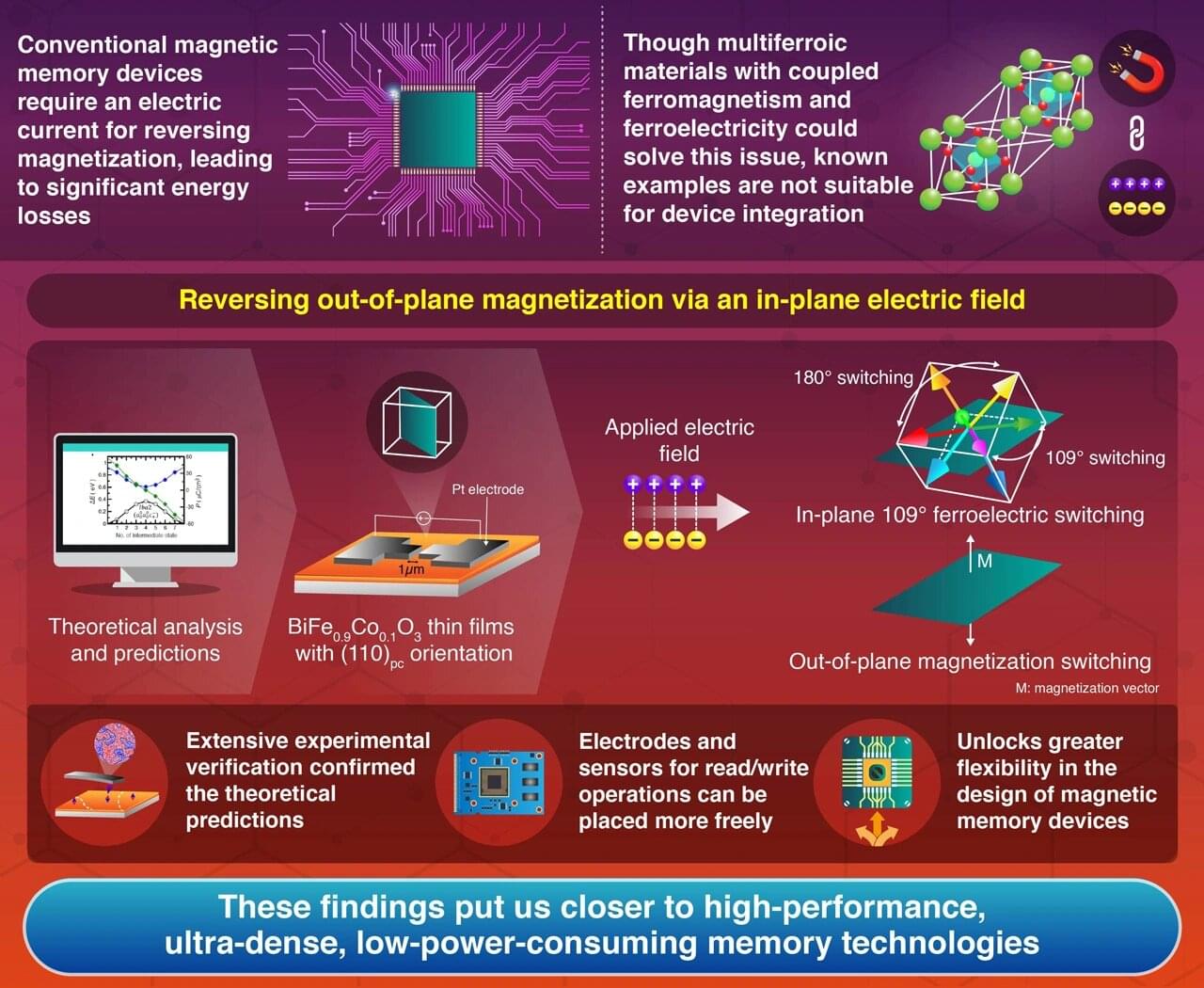

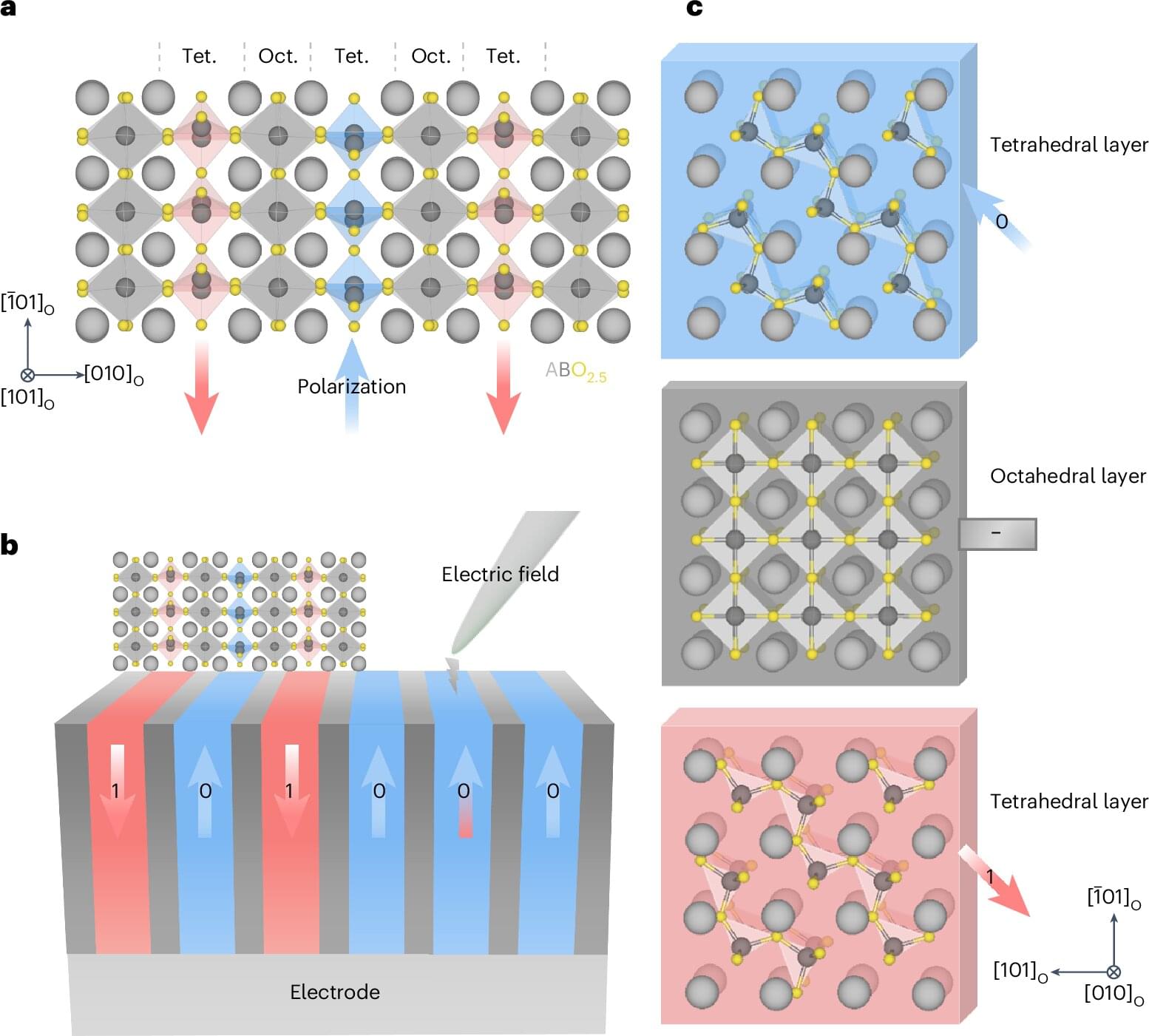

A research team has discovered ferroelectric phenomena occurring at a subatomic scale in the natural mineral brownmillerite.

The team was led by Prof. Si-Young Choi from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and the Department of Semiconductor Engineering at POSTECH (Pohang University of Science and Technology), in collaboration with Prof. Jae-Kwang Lee’s team from Pusan National University, as well as Prof. Woo-Seok Choi’s team from Sungkyunkwan University. The work appears in Nature Materials.

Electronic devices store data in memory units called domains, whose minimum size limits the density of stored information. However, ferroelectric-based memory has been facing challenges in minimizing domain size due to the collective nature of atomic vibrations.