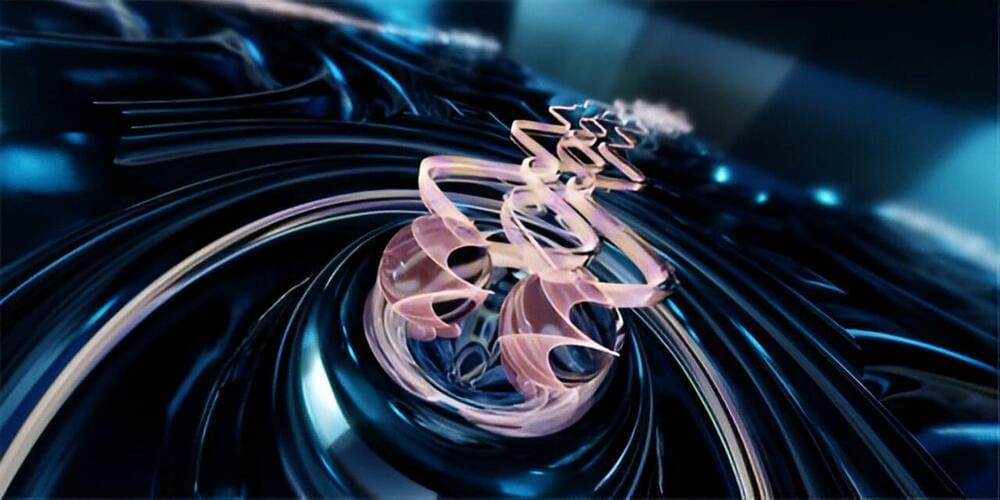

A study observes a triple protostar system with spiral arms of gas that feed material to baby stars and finds a new mechanism for multiple star formation.

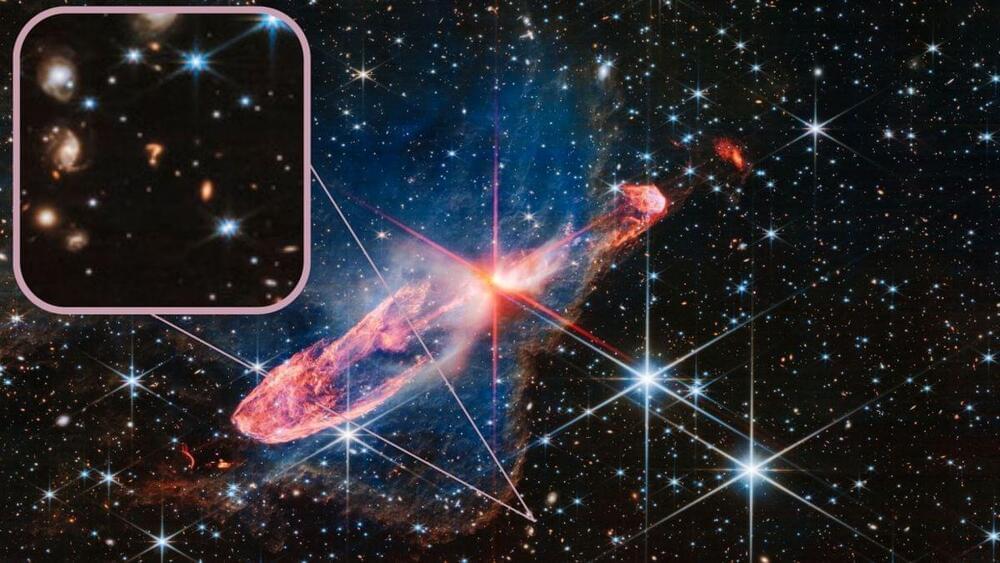

A team of international researchers has discovered how three baby stars are being fed by spiral arms of gas in a triple protostar system. The team, led by Professor Jeong-Eun Lee from Seoul National University, used the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescopes to observe the system called IRAS 04239+2436, located about 460 light-years away from Earth.

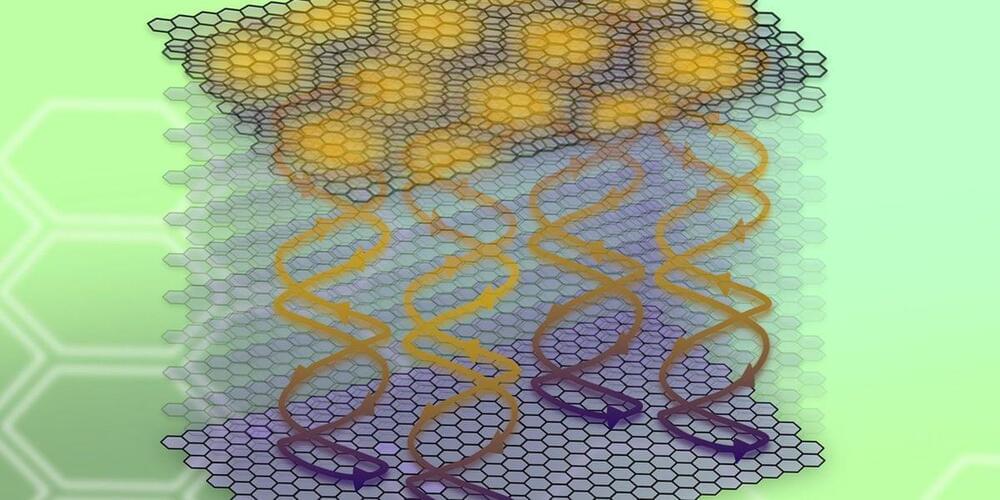

They found that the gas around the three protostars contains sulfur monoxide (SO) molecules, which indicates the presence of shock waves caused by the complex… More.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)