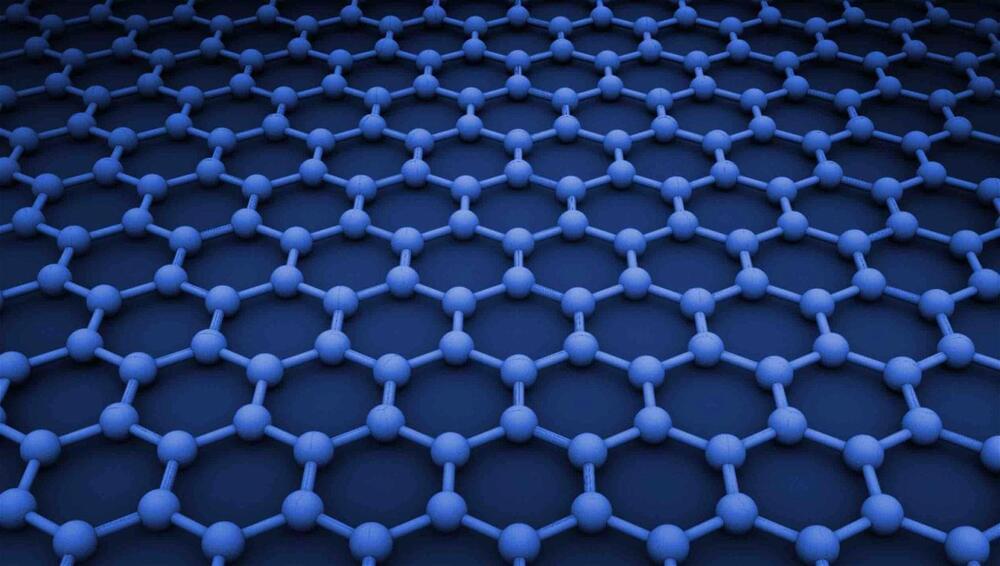

A team of researchers reports they have succeeded in disproving a long-held tenet of modern physics–that useful work cannot be obtained from random thermal fluctuations–thanks in part to the unique properties of graphene.

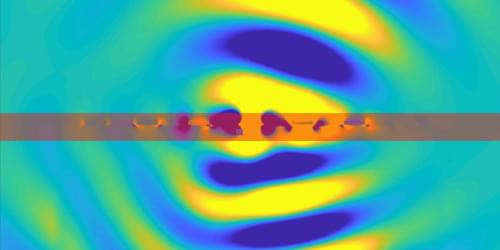

The microscopic motion of particles within a fluid, otherwise known as Brownian motion for its discovery by Scottish scientist Robert Brown, has long been considered an impossible means of attempting to generate useful work.

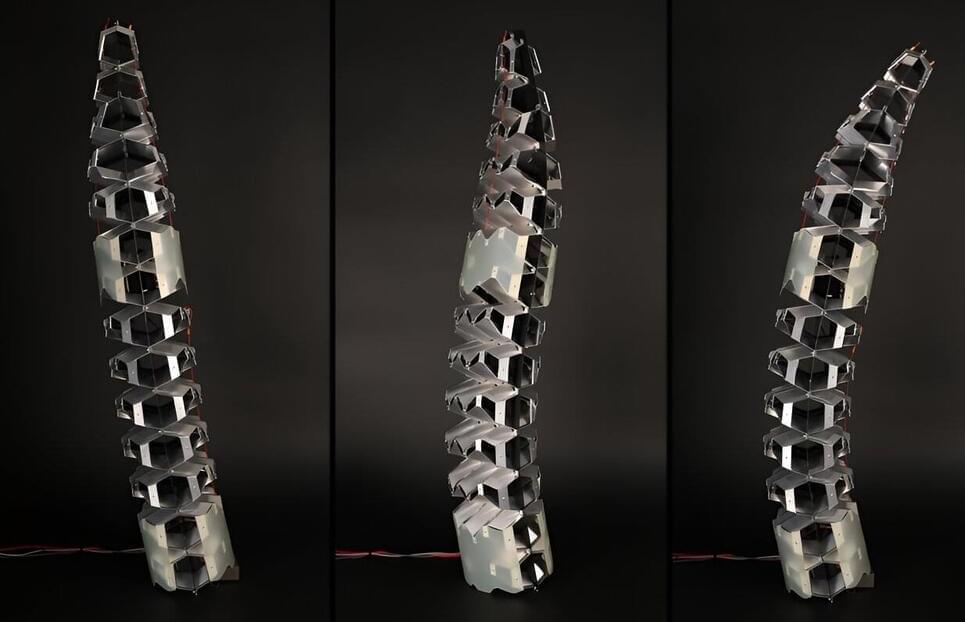

The idea had been most famously laid to rest decades ago by physicist Richard Feynman, who proposed a thought experiment in May 1962 involving an apparent perpetual motion machine, dubbed a Brownian ratchet.