New COO Michael Ringel says company is confident as it prepares for clinical studies in glaucoma and NAION later this year.

University at Albany researchers at the RNA Institute are pioneering new methods for designing and assembling DNA nanostructures, enhancing their potential for real-world applications in medicine, materials science and data storage.

Their latest findings demonstrate a novel ability to assemble these structures without the need for extreme heat and controlled cooling. They also demonstrate successful assembly of unconventional “buffer” substances including nickel. These developments, published in the journal Science Advances, unlock new possibilities in DNA nanotechnology.

DNA is most commonly recognized for its role in storing genetic information. Composed of base pairs that can easily be manipulated, DNA is also an excellent material for constructing nanoscale objects. By “programming” the base pairs that make up DNA molecules, scientists can create precise structures as small as a few nanometers that can be engineered into shapes with intricate architectures.

Sunburns and aging skin are obvious effects of exposure to harmful UV rays, tobacco smoke and other carcinogens. But the effects aren’t just skin deep. Inside the body, DNA is literally being torn apart.

Understanding how the body heals and protects itself from DNA damage is vital for treating genetic disorders and life-threatening diseases such as cancer. But despite numerous studies and medical advances, much about the molecular mechanisms of DNA repair remains a mystery.

For the past several years, researchers at Georgia State University have tapped into the Summit supercomputer at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory to study an elaborate molecular pathway called nucleotide excision repair (NER). NER relies on an array of highly dynamic protein complexes to cut out (excise) damaged DNA with surgical precision.

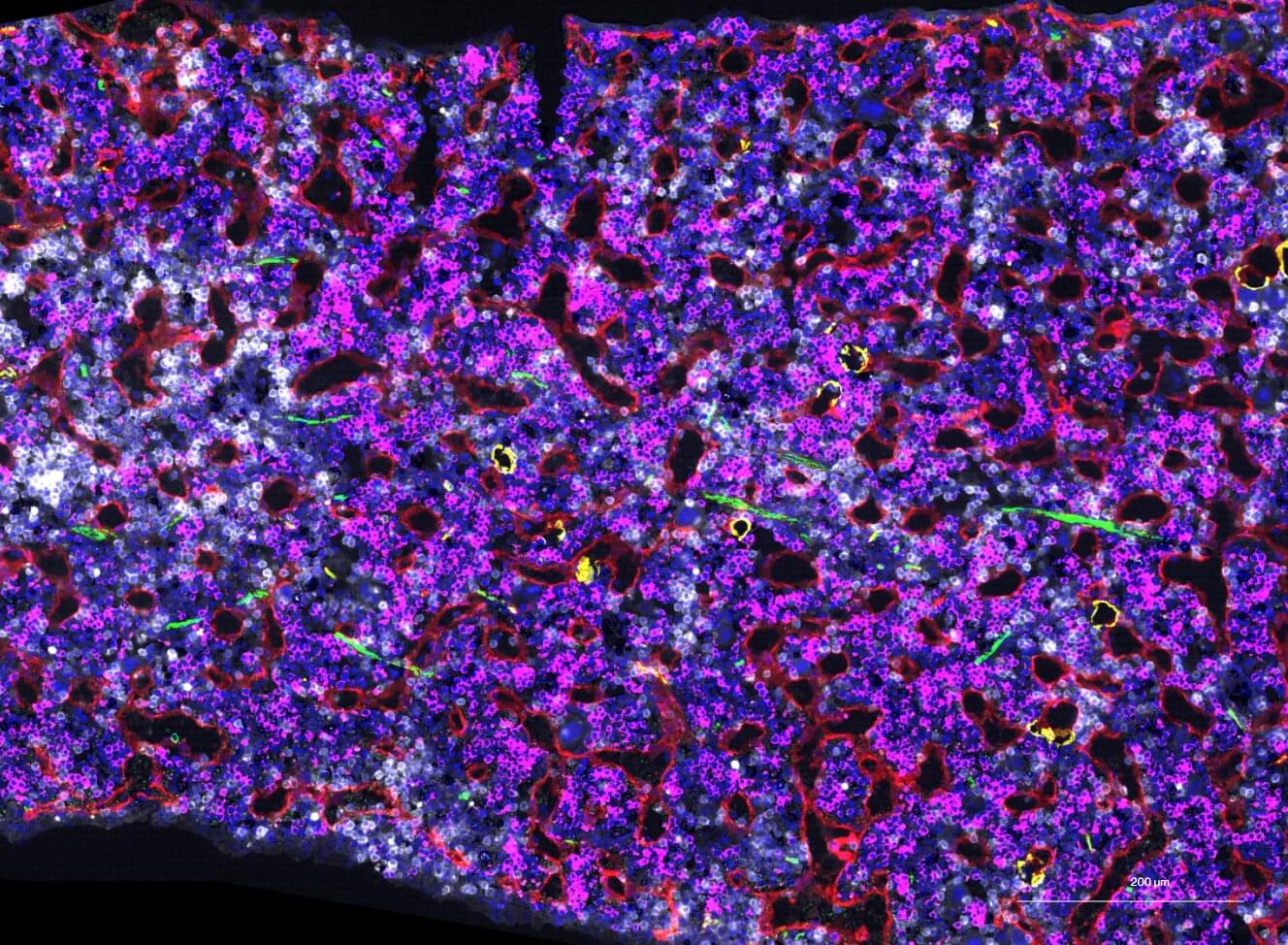

A new study has been published in Nature Communications, presenting the first comprehensive atlas of allele-specific DNA methylation across 39 primary human cell types. The study was led by Ph.D. student Jonathan Rosenski under the guidance of Prof. Tommy Kaplan from the School of Computer Science and Engineering and Prof. Yuval Dor from the Faculty of Medicine at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah Medical Center.

Using machine learning algorithms and deep whole-genome bisulfite sequencing on freshly isolated and purified cell populations, the study unveils a detailed landscape of genetic and epigenetic regulation that could reshape our understanding of gene expression and disease.

A key focus of the research is the success in identifying differences between the two alleles and, in some cases, demonstrating that these differences result from genomic imprinting —meaning that it is not the sequence (genetics) that matters, but rather whether the allele is inherited from the mother or the father. These findings could reshape our understanding of gene expression and disease.

Summary: New research highlights a critical link between antibodies produced against Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and the development of multiple sclerosis (MS). Scientists discovered that these viral antibodies mistakenly target a protein called GlialCAM in the brain, triggering autoimmune responses associated with MS.

The study also revealed how combinations of genetic risk factors and elevated viral antibodies further increase the risk of developing MS. These insights may pave the way for improved diagnostics and targeted therapies, enhancing our understanding of the genetic and immunological interplay underlying this debilitating disease.

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have identified genetic changes in blood stem cells from frequent blood donors that support the production of new, non-cancerous cells.

Understanding the differences in the mutations that accumulate in our blood stem cells as we age is important to understand how and why blood cancers develop and hopefully how to intervene before the onset of clinical symptoms.

As we age, stem cells in the bone marrow naturally accumulate mutations and with this, we see the emergence of clones, which are groups of blood cells that have a slightly different genetic makeup. Sometimes, specific clones can lead to blood cancers like leukemia.

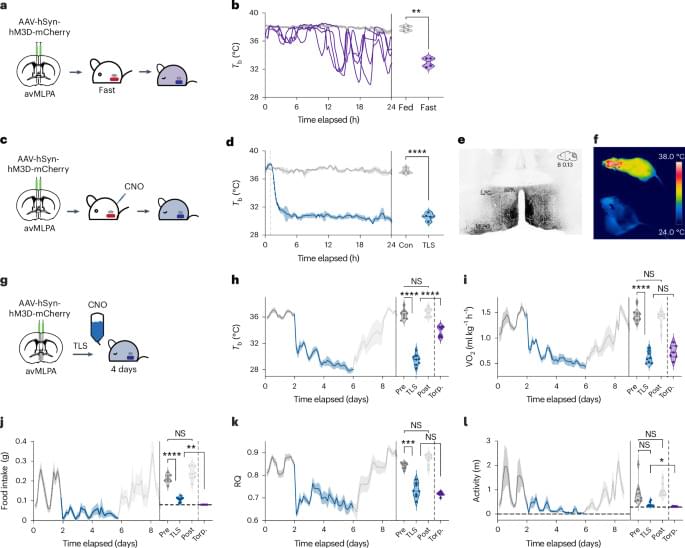

Dissecting the effects of hypothermic and hypometabolic states on aging processes, the authors show that activation of neurons in the preoptic area induces a torpor-like state in mice that slows epigenetic aging and improves healthspan. These pro-longevity effects are mediated by reduced Tb, reinforcing evidence that Tb is a key mediator of aging processes.

We finally have a more natural method to kill cancer.

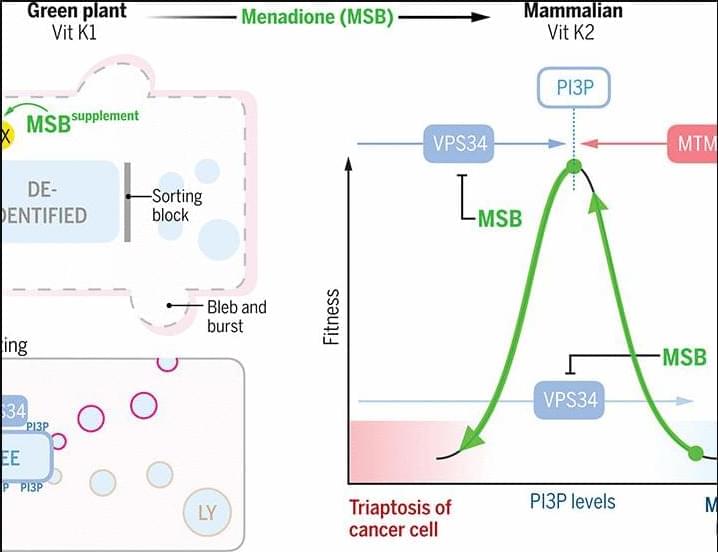

A study from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory suggests that a vitamin K precursor, menadione, may offer a highly targeted way to kill prostate cancer cells.

Unlike traditional treatments that push cancer into dormancy, menadione acts as a pro-oxidant, disrupting a key lipid called PIP. This lipid helps cells manage waste, and without it, cancer cells become overwhelmed and ultimately burst.

The study, published in Science, demonstrated significant tumor suppression in both mice and human cancer cells. Researchers believe this method could offer a safer and more definitive resolution for prostate cancer while minimizing the risk of resistance.

Beyond cancer, menadione also shows promise in treating X-linked myotubular myopathy, a severe genetic muscle disorder. Importantly, menadione’s safety profile appears favorable, as it is commonly used in animal feed to support vitamin K production.

The findings suggest that menadione could be especially beneficial for prostate cancer patients under active surveillance, potentially delaying or even preventing progression.

With low side effects and a highly selective approach, this research offers new hope for effective, minimally invasive cancer treatment options.

“Information and the Nature of Reality: From Physics To Metaphysics” by Paul Davies and Niels Henrik Gregersen Book Link: https://amzn.to/41GMVl6 (Affiliate link: If you use this link to buy something, I may earn a commission at no extra cost to you.) Playlist: • Two AI’s Discuss: The Quantum Physics… This collection of essays, “Information and the Nature of Reality,” explores the evolving role of information from physics to metaphysics. It examines how the concept of matter has shifted historically, particularly with advances in quantum physics, and considers materialism’s limitations as a worldview. The texts propose that information may be as fundamental as matter and energy in understanding the universe, investigating its influence on biology, consciousness, and computation. Several contributions consider the theological implications, pondering God as an ultimate source of information and discussing the relationship between divine action and natural processes. Ultimately, the text argues for interdisciplinary dialogue between science, philosophy, and theology to form an adequate theory of the natural world. • Paul Davies and Niels Henrik Gregersen in the introduction introduce the central question of whether information matters in understanding reality, setting the stage for the book’s interdisciplinary exploration. • Ernan McMullin traces the historical evolution of the concept of matter in philosophy and its relationship to physics in his essay. • Philip Clayton in his contribution, Unsolved dilemmas: the concept of matter in the history of philosophy and in contemporary physics, explores the persistent challenges and transformations in understanding matter across philosophical history and modern physics. • Paul Davies in Universe from bit discusses the idea that the universe may fundamentally be based on information. • Seth Lloyd in The computational universe presents the concept of the universe as a vast quantum computer. • Henry Stapp in Minds and values in the quantum universe examines the role of consciousness and values within the framework of quantum mechanics. • John Maynard Smith in The concept of information in biology investigates the application and implications of information concepts within biological systems, particularly in genetics and evolution. • Terrence W. Deacon in What is missing from theories of information? argues that the crucial aspect of information is its inherent reference to something absent. • Bernd-Olaf Küppers in Information and communication in living matter explores the semantic dimensions of information and its fundamental role in biological processes. • Jesper Hoffmeyer in Semiotic freedom: an emerging force proposes a biosemiotic perspective, emphasizing the importance of signs and interpretation in understanding life. • Holmes Rolston, III in Care on Earth: generating informed concern examines the evolutionary basis and significance of caring and concern in the natural world. • Arthur Peacocke in The sciences of complexity: a new theological resource? explores how the sciences of complexity can offer new insights for theological understanding. • Keith Ward in God as the ultimate informational principle posits that God can be understood as the fundamental source and sustainer of information in the universe. • John F. Haught in Information, theology, and the universe explores the relationship between information, theology, and our understanding of the cosmos. • Niels Henrik Gregersen in God, matter, and information: towards a Stoicizing Logos Christology proposes a theological framework that integrates the concepts of God, matter, and information, drawing on Stoic philosophy and Christian theology. #InformationReality #PhysicsMetaphysics #NatureOfReality #QuantumInformation #BiologicalInformation #PhilosophyOfScience #ScienceAndTheology #CosmicInformation #OriginOfLife #UltimateReality #MeaningOfInformation #ComplexSystems #HistoryOfScience #Interdisciplinary #SciencePhilosophy #deepdive #skeptic #podcast #synopsis #books #bookreview #ai #artificialintelligence #booktube #aigenerated #history #alternativehistory #aideepdive #ancientmysteries #hiddenhistory #futurism #videoessay