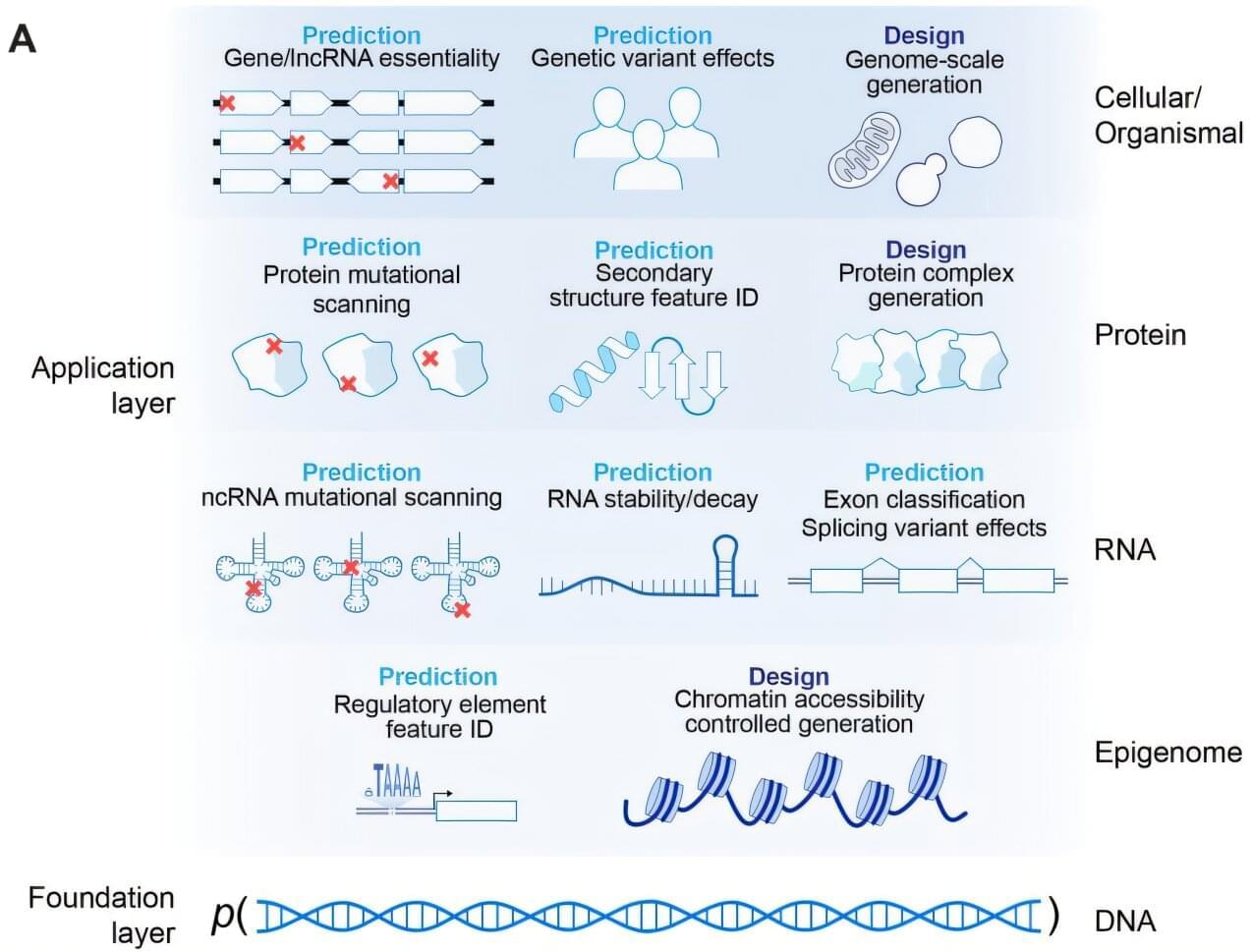

Dr. Michael Levin’s groundbreaking research redefines intelligence, agency, and selfhood, showing that it exists not just in brains but across all levels of biological systems—cells, organs, and entire organisms. Through his concept of the “morphogenetic code,” Levin reveals that bioelectric signals, not just DNA, guide cellular organization and behavior, enabling profound regenerative breakthroughs like limb regrowth and functional organ creation. His work extends into philosophy, reshaping how we view alien life, selfhood, and even the nature of existence by framing life as an emergent property of interconnected intelligences. Levin envisions tools like an “anatomical compiler” to revolutionize medicine and challenges us to rethink life, intelligence, and the cosmos, solidifying his place as one of the most important living scientists.

Deep Thinkers, Check This: https://www.skool.com/yoda/about.