Landmark study identifies the genes that it seems people can and cannot live without and highlights ongoing challenges in making data sets more representative of the world’s population.

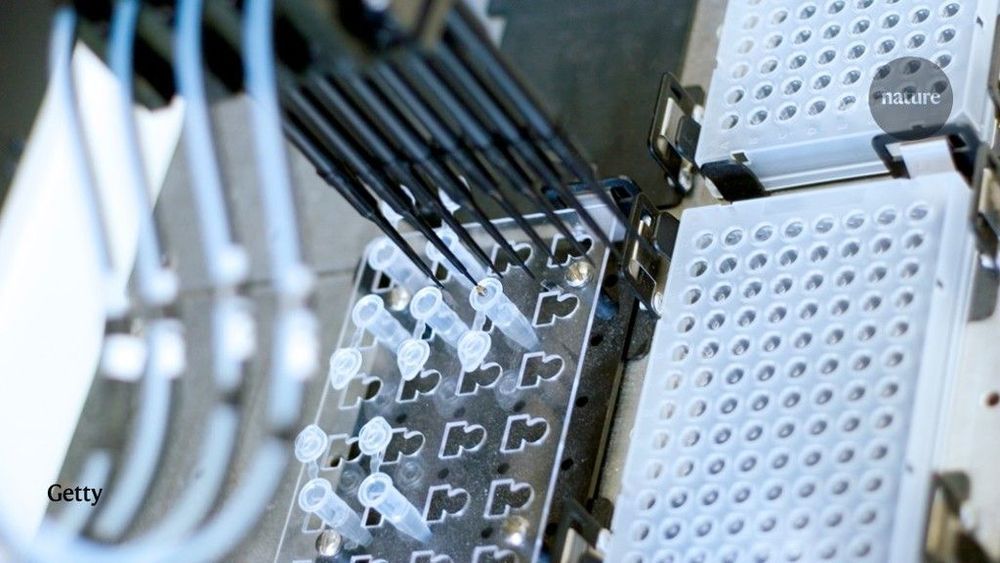

CRISPR gene-editing trials have taken off—and may hold the key to medical breakthroughs.

[Illustration: Jamie Cullen]

A key epigenetic mark can block the binding of an important gene regulatory protein, and therefore prohibit the gene from being turned off, a new UNSW study in CRISPR-modified mice—published this month in Nature Communications —has shown.

The study has implications for understanding how epigenetics works at a molecular level—and down the track, the scientists hope the research will help them to investigate new treatments for blood disorders.

“Epigenetics looks at how non-permanent, acquired chemical marks on DNA determine whether or not particular genes are expressed,” study leader and UNSW Professor Merlin Crossley says.

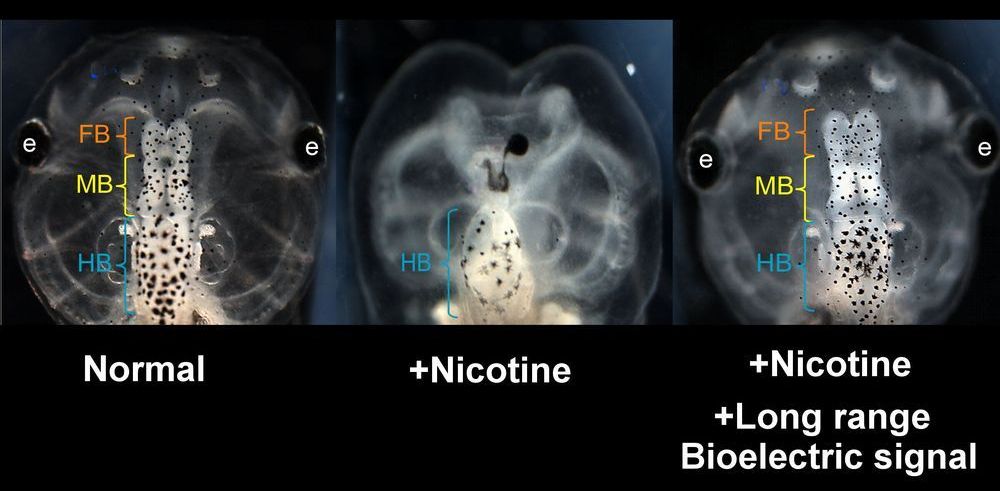

Researchers led by biologists at Tufts University have discovered that the brains of developing frog embryos damaged by nicotine exposure can be repaired by treatment with certain drugs called “ionoceuticals” that drive the recovery of bioelectric patterns in the embryo, followed by repair of normal anatomy, gene expression and brain function in the growing tadpole. The research, published today in Frontiers in Neuroscience, introduces intervention strategies based on restoring the bioelectric “blueprint” for embryonic development, which the researchers suggest could provide a roadmap for the exploration of therapeutic drugs to help repair birth defects.

It was January of 1980 when 21-year-old Helene Pruszynski was kidnapped, raped and murdered in Douglas County, Colorado. Her body was found in a field, but police never identified a suspect. Pruszynski’s murder became a cold case.

“We consider a case that does not have any viable leads after one to two years a cold case,” cold case detective Shannon Jensen said.

However, Jensen says the case was never forgotten. Detectives continued to re-open it for 40 years. Then, with the help of new DNA technology, the suspect was identified in December of last year as James Curtis Clanton. He will be sentenced on April 10, based on the first-degree murder laws in 1980.

A molecule commonly produced by gut microbes appears to improve memory in mice.

A new study is among the first to trace the molecular connections between genetics, the gut microbiome, and memory in a mouse model bred to resemble the diversity of the human population.

While tantalizing links between the gut microbiome and brain have previously been found, a team of researchers from two U.S. Department of Energy national laboratories found new evidence of tangible connections between the gut and the brain. The team identified lactate, a molecule produced by all species of one gut microbe, as a key memory-boosting molecular messenger. The work was published recently in the journal BMC Microbiome.

WUHAN, China — As the worldwide number of COVID-19 cases reaches five million, the search for a vaccine has taken an important step forward. Researchers say the first human trial of a possible vaccine has been found to be safe and may effectively fight the virus.

Scientists in China say 108 healthy adults were given a dose of adenovirus type 5 vectored COVID-19 (Ad5-nCoV) during the trial. The drug uses a weakened strain of the common cold (adenovirus) to deliver genetic material which codes itself to find the protein in SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes COVID-19. These coded cells then head to the lymph nodes where the immune system creates antibodies that can recognize the virus and attack it.

“These results represent an important milestone. The trial demonstrates that a single dose of the new adenovirus type 5 vectored COVID-19 (Ad5-nCoV) vaccine produces virus-specific antibodies and T cells in 14 days,” Professor Wei Chen of the Beijing Institute of Biotechnology said in a statement.

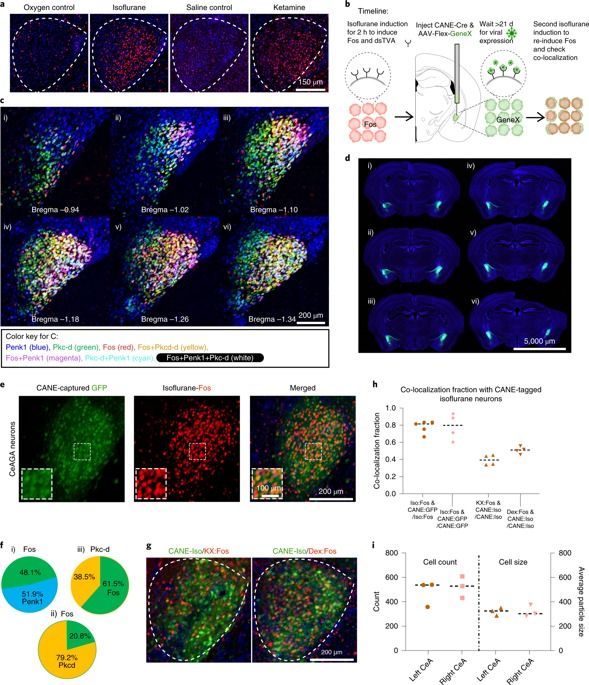

General anesthesia (GA) can produce analgesia (loss of pain) independent of inducing loss of consciousness, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We hypothesized that GA suppresses pain in part by activating supraspinal analgesic circuits. We discovered a distinct population of GABAergic neurons activated by GA in the mouse central amygdala (CeAGA neurons). In vivo calcium imaging revealed that different GA drugs activate a shared ensemble of CeAGA neurons also possess basal activity that mostly reflects animals’ internal state rather than external stimuli. Optogenetic activation of CeAGA potently suppressed both pain-elicited reflexive and self-recuperating behaviors across sensory modalities and abolished neuropathic pain-induced mechanical (hyper-)sensitivity. Conversely, inhibition of CeAGA activity exacerbated pain, produced strong aversion and canceled the analgesic effect of low-dose ketamine. CeAGA neurons have widespread inhibitory projections to many affective pain-processing centers. Our study points to CeAGA as a potential powerful therapeutic target for alleviating chronic pain.

Maximizing the protection of life on Earth requires knowledge of the global patterns of biodiversity at multiple dimensions, from genetic diversity within species, to species and ecosystem diversity. Yet, the lack of genetic sequences with geographic information at global scale has so far hindered our ability to map genetic diversity, an important, but hard to detect, biodiversity dimension.

In a new study, researchers from the Universities of Copenhagen and Adelaide have collected and georeferenced a massive amount of genetic data for terrestrial mammals and evaluated long-standing theories that could explain the global distribution of genetic diversity. They found that regions of the world rich in deep evolutionary history, such as Northern Andes, the Eastern Arc Mountains, Amazonia, the Brazilian Atlantic forest, the central America jungles, sub-Saharan Africa and south-eastern Asia are also strongholds of genetic diversity. They also show that the relatively stable climate in these regions during the past 21’000 years contributes significantly to this intraspecific richness.

“Genetic diversity within species is a critical component of biodiversity, playing two important roles at the same time. It reflects species evolutionary history and defines their capacity to adapt under future environmental change. However, and despite the predictions of major biodiversity theories, the actual global distribution of genetic diversity remained, so far, a mystery. Recent collective efforts to populate public databases with genetic sequences and their localities allowed us to evaluate these theories and generate the first global maps of genetic diversity in terrestrial mammal assemblages”, says Spyros Theodoridis, Postdoctoral Researcher at the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, GLOBE Institute, and lead author of the study.