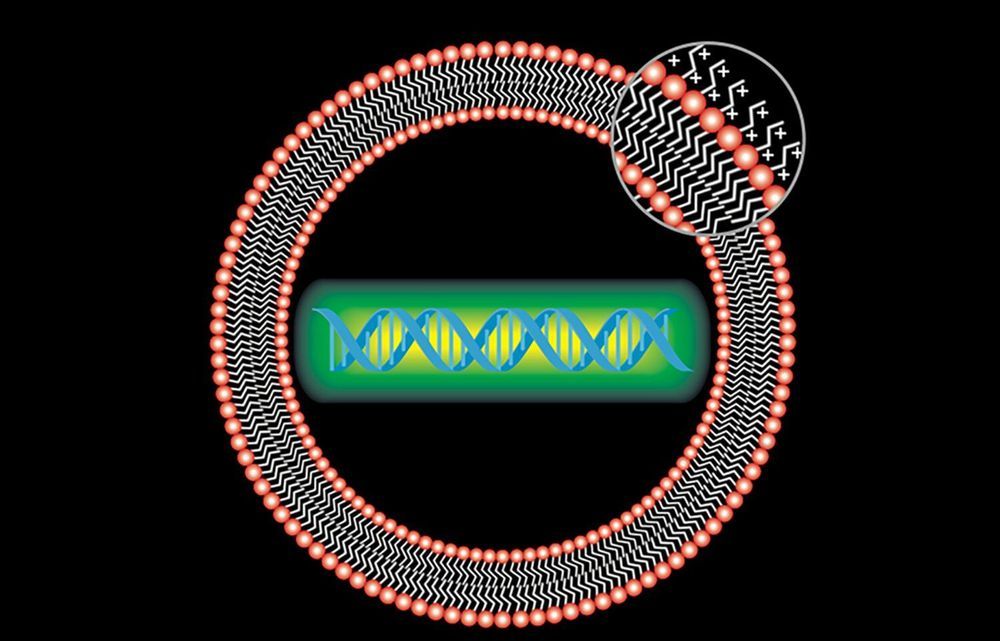

Chronic stress has long been associated with the pathogenesis of psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety. Recent studies have found chronic stress can cause neuroinflammation: activation of the resident immune cells in the brain, microglia, to produce inflammatory cytokines. Numerous studies have implicated the inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1 (IL-1), a master regulator of immune cell recruitment and activity in the brain, as the key mediator of psychopathology. However, how IL-1 disrupts neural circuits to cause behavioral and emotional problems seen in psychological disorders has not been determined.

…

The research team previously detailed how psychosocial stress results in peripheral immune activation, increased levels of circulating monocytes, and robust neuroimmunological responses in the brain. These responses include increases in IL-1 and other inflammatory cytokines, activation of brain glial cells and movements of peripheral immune cells to the brain, along with enhanced activity of specific neuronal pathways. The work makes it clear that inflammatory-related effects of stress are not just global effects, but are associated with increased IL-1 signaling within specific brain circuits.

The study shows for the first time that neuronal IL-1Rs in the hippocampus, a brain structure connected to learning and memory, is necessary and sufficient to mediate some of the behavioral deficits caused by chronic stress, pointing to a critical neuroimmune mechanism for the etiology of these types of disorders. Findings from the study augment the understanding of IL-1R signaling in physiological and behavioral responses to stress and also suggest that it may be possible to develop better medications to treat the consequences of chronic stress by limiting inflammatory signaling not just generally, which may not be beneficial in the long run, but to specific brain circuits.

“We created and validated a unique genetic mouse model to restrict IL-1R1 expression to different cell types to visualize and control IL-1Rs,” said Ning Quan, Ph.D., lead author, a professor of biomedical science in FAU’s Schmidt College of Medicine, and a member of the FAU Brain Institute (I-BRAIN). “We demonstrated that chronic social stress caused the mice to show social withdrawal and working memory deficits. These changes could be prevented if the neuronal IL-1R1 was deleted and restored if IL-1R1 was only allowed to be expressed on hippocampal neurons.”

For the study, researchers wanted to determine the degree to which IL-1 acts directly on hippocampal neurons to influence cognitive and mood changes with stress. To define the IL-1R-mediated neuronal response, they used novel and comprehensive IL-1R transgenic/reporter lines in which one can selectively delete IL-1R or restore IL-1R on specific cell types, including glutamatergic neurons. They also used modified viruses to manipulate hippocampal neurons and investigate the role of IL-1R in eliciting behavioral responses to stress. Their data show that social defeat-induced IL-1R signaling in hippocampal neurons perpetuated inflammation and promoted deficits in social interaction and working memory.