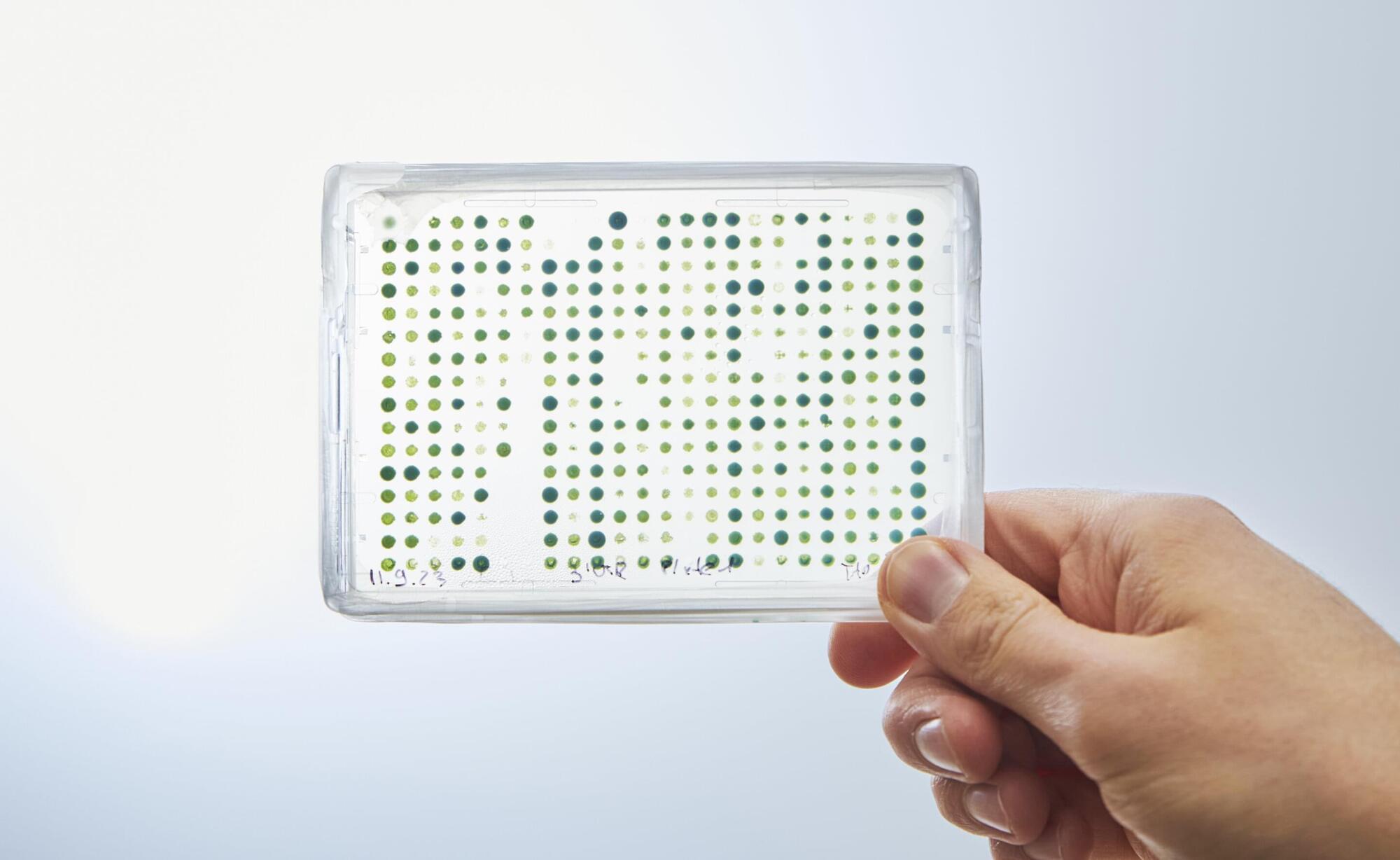

Scientists from Oxford’s Radcliffe Department of Medicine have achieved the most detailed view yet of how DNA folds and functions inside living cells, revealing the physical structures that control when and how genes are switched on.

Using a new technique called MCC ultra, the team mapped the human genome down to a single base pair, unlocking how genes are controlled, or, how the body decides which genes to turn on or off at the right time, in the right cells. This breakthrough gives scientists a powerful new way to understand how genetic differences lead to disease and opens up fresh routes for drug discovery.

“For the first time, we can see how the genome’s control switches are physically arranged inside cells, said Professor James Davies, lead author of the study published in the journal Cell titled ” Mapping chromatin structure at base-pair resolution unveils a unified model of cis-regulatory element interactions.”