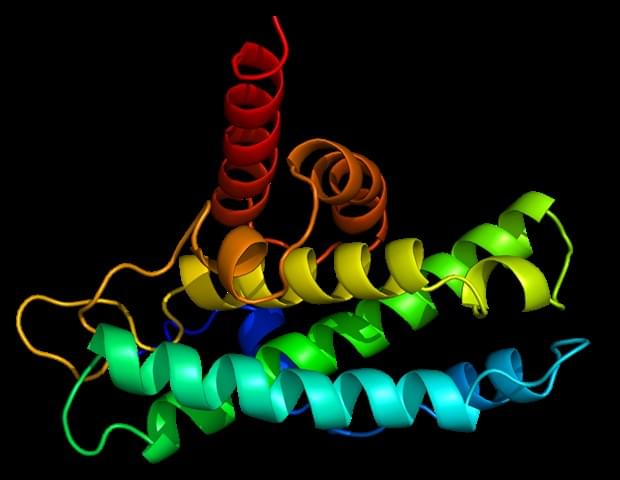

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published Phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with pre-specified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at The Scripps Research Institute and study co-author, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Schief said in a news release.