Say hello to artificial bacterium syn-3, now with “swimming” powers thanks to genetic tinkering.

Category: genetics – Page 289

Cancer Weakness Discovered: New Method Pushes Cancer Cells Into Remission

Cancer cells delete DNA

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is a molecule composed of two long strands of nucleotides that coil around each other to form a double helix. It is the hereditary material in humans and almost all other organisms that carries genetic instructions for development, functioning, growth, and reproduction. Nearly every cell in a person’s body has the same DNA. Most DNA is located in the cell nucleus (where it is called nuclear DNA), but a small amount of DNA can also be found in the mitochondria (where it is called mitochondrial DNA or mtDNA).

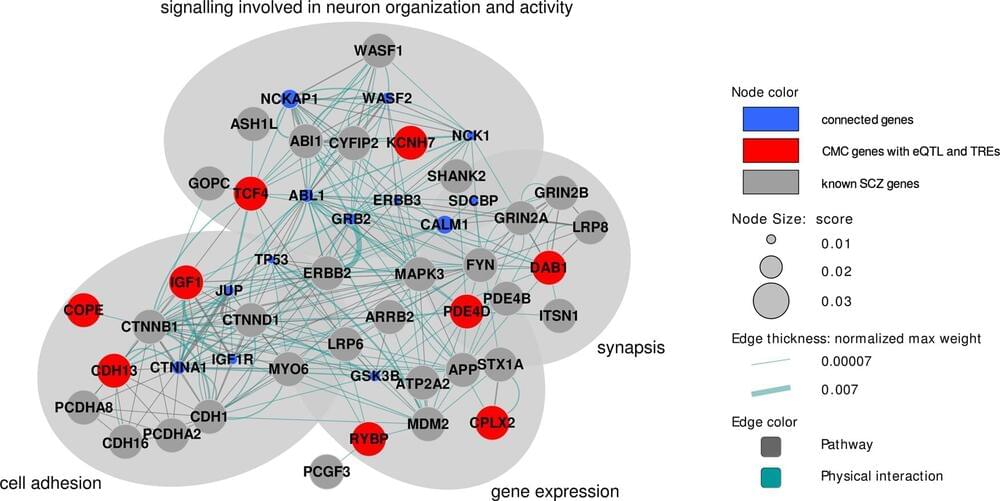

Scientists link rare genetic phenomenon to neuron function, schizophrenia

In our cells, the language of DNA is written, making each of us unique. A tandem repeat occurs in DNA when a pattern of one or more nucleotides—the basic structural unit of DNA coded in the base of chemicals cytosine ©, adenine (A), guanine (G) and thymine (T)—is repeated multiple times in tandem. An example might be: CAG CAG CAG, in which the pattern CAG is repeated three times.

Now, using state-of-the-art whole-genome sequencing and machine learning techniques, the UNC School of Medicine lab of Jin Szatkiewicz, Ph.D., associate professor of genetics, and colleagues conducted one of the first and the largest investigations of tandem repeats in schizophrenia, elucidating their contribution to the development of this devastating disease.

Published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, the research shows that individuals with schizophrenia had a significantly higher rate of rare tandem repeats in their genomes—7% more than individuals without schizophrenia. And they observed that the tandem repeats were not randomly located throughout the genome; they were primarily found in genes crucial to brain function and known to be important in schizophrenia, according to previous studies.

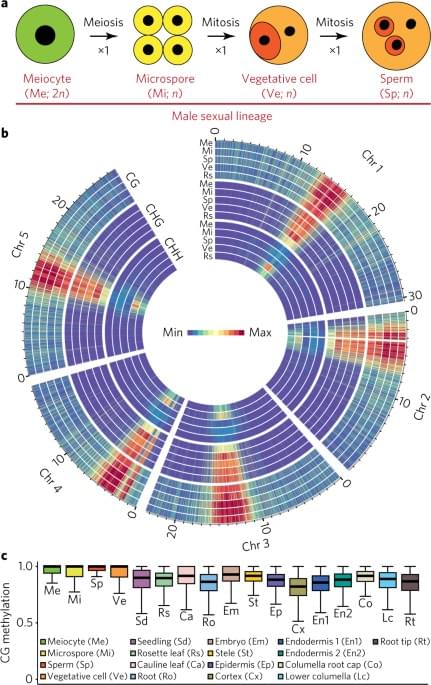

Sexual-lineage-specific DNA methylation regulates meiosis in Arabidopsis

Year 2017 This is essentially the mechanism for plant immortality.

RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) activity in the Arabidopsis thaliana male sexual lineage that regulates gene expression in meiocytes. Loss of sexual-lineage-specific RdDM causes mis-splicing of the MPS1 gene (also known as PRD2), thereby disrupting meiosis. Our results establish a regulatory paradigm in which de novo methylation creates a cell-lineage-specific epigenetic signature that controls gene expression and contributes to cellular function in flowering plants.

How tardigrades come back from the dead

Year 2017 Basically the tardigrade is the most promising set of genes on any creature due to many types of survival genes like going years without food or even genes for radiation resistance which could be used in crispr to augment human genes.

Tardigrades — aka water bears or moss piglets — are perhaps the most resilient creatures on the planet, able to survive complete dehydration, space vacuum and being frozen. However, only recently have scientists begun to unravel the genes that underpin the tardigrade’s biological superpowers. “They’re 0.2mm to 1mm in length and despite being so small they are able to do all these things we cannot,” says Mark Blaxter, a biologist at the University of Edinburgh who has been studying tardigrades for 20 years. “In their DNA, they hold a cornucopia of secrets.”

With Kazurahu Arakawa, from the University of Keio, Japan, Blaxter recently analysed the first true tardigrade genome. The results, published today in the open access journal PLOS Biology, are a first step towards explaining the genetics underpinning the tardigrade’s extraordinary resilience and to pinpoint its place within the evolutionary tree of life. We spoke to Blaxter about his new research and his fascination for this remarkable little animal.

**WIRED:**How come we are only now able to analyse the tardigrade’s true genomes?

Can ‘Blueprint’ make you biologically younger?

If you enjoyed this video, you might like my book: https://ageless.link/

I saw a Twitter thread about Bryan Johnson’s ‘Blueprint’, claiming that he’d made himself biologically younger with a highly optimised combination of diet, supplements and exercise. What could that mean? And should we all start chugging 25 pills a day to start on the Blueprint ourselves? Probably not…but the biology behind it is surprisingly interesting.

*Chapters*

00:00 A tweet goes viral.

00:44 Getting ‘biologically younger’

01:23 NAD levels.

03:09 Maximum heart rate.

04:12 Epigenetic clocks.

07:12 Step 1: the Blueprint diet.

09:23 Step 2: ALL THE SUPPLEMENTS

11:43 Step 3: track progress.

12:40 Conclusion.

*Sources and further reading*

My book, Ageless: The new science of getting older without getting old, goes into far more depth about rapamycin, metformin and epigenetic clocks, and lots more! https://ageless.link/

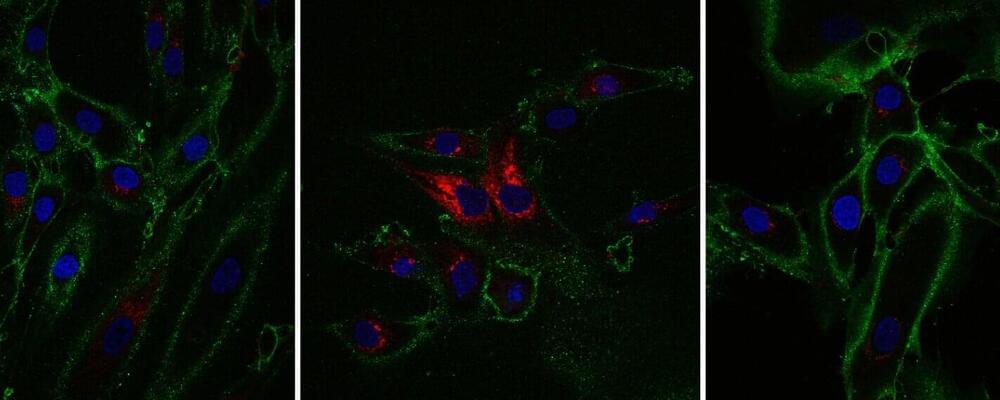

Old skin cells reprogrammed to regain youthful function

Research from the Babraham Institute has developed a method to “time jump” human skin cells by 30 years, turning back the aging clock for cells without losing their specialized function. Work by researchers in the Institute’s Epigenetics research program has been able to partly restore the function of older cells, as well as rejuvenating the molecular measures of biological age. The research is published today in the journal eLife, and while this topic is still at an early stage of exploration, it could revolutionize regenerative medicine.

What is regenerative medicine?

As we age, our cells’ ability to function declines and the genome accumulates marks of aging. Regenerative biology aims to repair or replace cells including old ones. One of the most important tools in regenerative biology is our ability to create “induced” stem cells. The process is a result of several steps, each erasing some of the marks that make cells specialized. In theory, these stem cells have the potential to become any cell type, but scientists aren’t yet able to reliably recreate the conditions to re-differentiate stem cells into all cell types.

Michael Levin | Cell Intelligence in Physiological & Morphological Spaces

Talk kindly contributed by Michael Levin in SEMF’s 2022 Spacious Spatiality.

https://semf.org.es/spatiality.

TALK ABSTRACT

Life was solving problems in metabolic, genetic, physiological, and anatomical spaces long before brains and nervous systems appeared. In this talk, I will describe remarkable capabilities of cell groups as they create, repair, and remodel complex anatomies. Anatomical homeostasis reveals that groups of cells are collective intelligences; their cognitive medium is the same as that of the human mind: electrical signals propagating in cell networks. I will explain non-neural bioelectricity and the tools we use to track the basal cognition of cells and tissues and control their function for applications in regenerative medicine. I will conclude with a discussion of our framework based on evolutionary scaling of intelligence by pivoting conserved mechanisms that allow agents, whether designed or evolved, to navigate complex problem spaces.

TALK MATERIALS

· The Electrical Blueprints that Orchestrate Life (TED Talk): https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_levin_the_electrical_bluep…trate_life.

· Michael Levin’s interviews and presentations: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/presentations/

· Michael Levin’s publications: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/publications/

· The Institute for Computationally Designed Organisms (ICDO): https://icdorgs.org/

MICHAEL LEVIN

Department of Biology, Tufts University: https://as.tufts.edu/biology.

Tufts University profile: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/

Wyss Institute profile: https://wyss.harvard.edu/team/associate-faculty/michael-levin-ph-d/

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Levin_(biologist)

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=luouyakAAAAJ

Twitter: https://twitter.com/drmichaellevin.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/michael-levin-b0983a6/

SEMF NETWORKS

These Mysterious Fungi Belong to an Entirely New Branch on The Tree of Life

Some of Earth’s weirdest fungi, including types of lichen, mycorrhizal, and insect symbiotes, never quite seemed to fit in our current tree of life.

But a new genetic analysis discovered that despite the extreme differences between these oddballs, they actually all belong together on an entirely new branch that parted ways with other fungi more than 300 million years ago.

“I like to think of these as the platypus and echidna of the fungal world,” says University of Alberta mycologist Toby Spribille, because of the fungi’s peculiar traits.