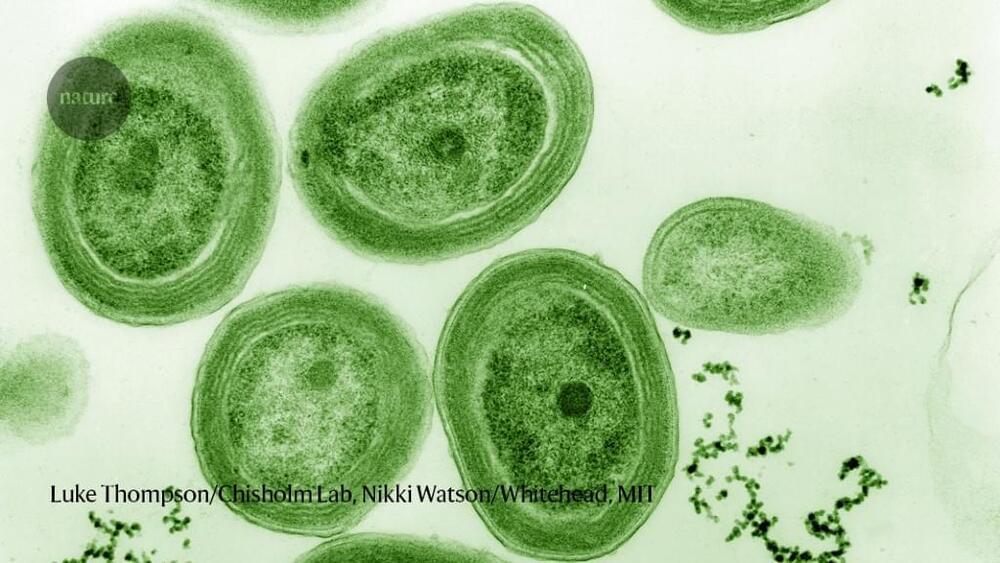

Our DNA is made up of genes that vary drastically in size. In humans, genes can be as short as a few hundred molecules known as bases or as long as two million bases. These genes carry instructions for constructing proteins and other information crucial to keeping the body running. Now a new study suggests that longer genes become less active than shorter genes as we grow older. And understanding this phenomenon could reveal new ways of countering the aging process.

Luís Amaral, a professor of chemical and biological engineering at Northwestern University, says he and his colleagues did not initially set out to examine gene length. Some of Amaral’s collaborators at Northwestern had been trying to pinpoint alterations in gene expression—the process through which the information in a piece of DNA is used to form a functional product, such as a protein or piece of genetic material called RNA—as mice aged. But they were struggling to identify consistent changes. “It seemed like almost everything was random,” Amaral says.

Then, at the suggestion of Thomas Stoeger, a postdoctoral scholar In Amaral’s lab, the team decided to consider shifts in gene length. Prior studies had hinted that there might be such a large-scale change in gene activity with age—showing, for example, that the amount of RNA declines over time and that disruptions to transcription (the process through which RNA copies, or transcripts, are formed from DNA templates) can have a greater impact on longer genes than shorter ones.