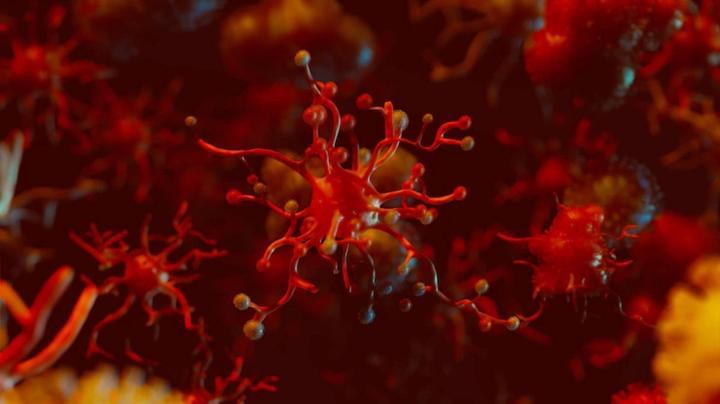

Could knowing where your ancestors came from be the key to better cancer treatments? Maybe, but where would that key fit? How can we trace cancer’s ancestral roots to modern-day solutions? For Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Research Professor Alexander Krasnitz, the answers may lie deep within vast databases and hospital archives containing hundreds of thousands of tumor samples.

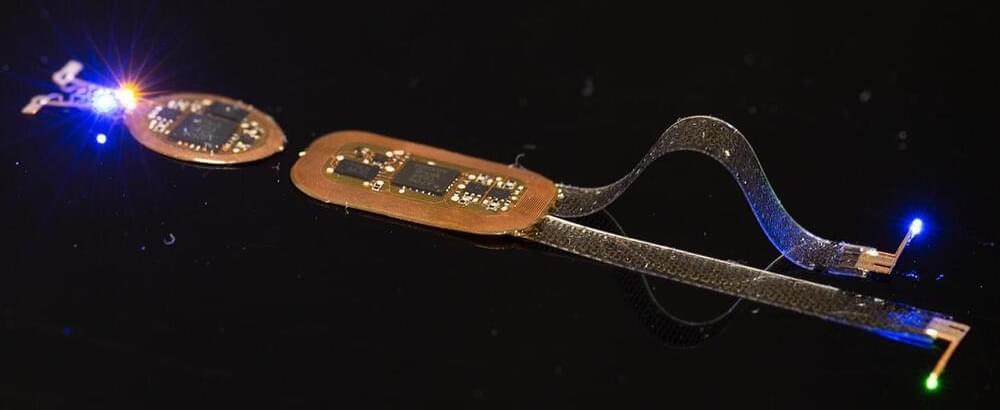

Krasnitz and CSHL Postdoctoral Fellow Pascal Belleau are working to reveal the genealogical connections between cancer and race or ethnicity. They’ve developed new software that accurately infers continental ancestry from tumor DNA and RNA. Their latest study is published in Cancer Research, and their work may help clinicians develop new strategies for early cancer detection and personalized treatments.

“Why do people of different races and ethnicities get sick at different rates with different types of cancer? They have different habits, living conditions, exposures—all kinds of social and environmental factors. But there may be a genetic component as well,” Krasnitz says.