With the summer holiday season now in full swing, the blog will also swing into its annual August series. For most of the month, I will share with you just a small sampling of the colorful videos and snapshots of life captured in a select few of the hundreds of NIH-supported research labs around the country.

To get us started, let’s turn to the study of viruses. Researchers now can generate vast amounts of data relatively quickly on a virus of interest. But data are often displayed as numbers or two-dimensional digital images on a computer screen. For most virologists, it’s extremely helpful to see a virus and its data streaming in three dimensions. To do so, they turn to a technological tool that we all know so well: animation.

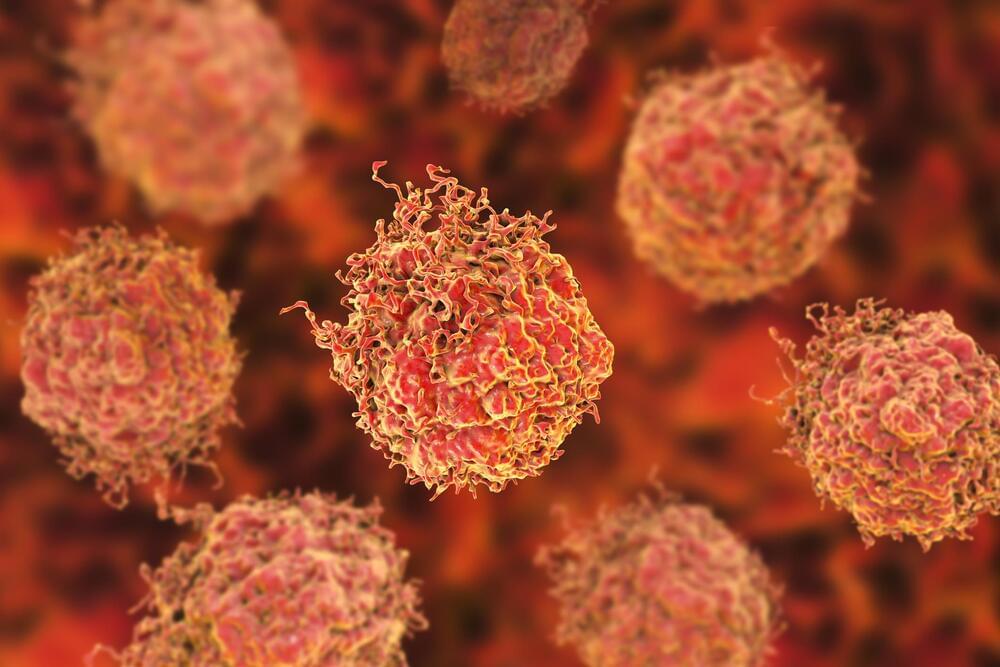

This research animation features the chikungunya virus, a sometimes debilitating, mosquito-borne pathogen transmitted mainly in developing countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas. The animation illustrates large amounts of research data to show how the chikungunya virus infects our cells and uses its specialized machinery to release its genetic material into the cell and seed future infections. Let’s take a look.