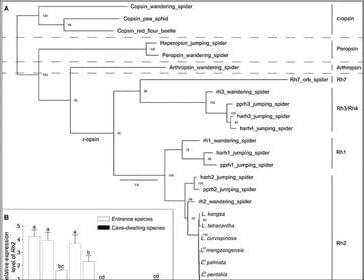

In this study, we conducted behavioral experiments and measured survival rates in local caves to minimize the impacts of factors other than light. Although energy-costly eyes were highly reduced or lost in cave-dwelling Leptonetela spiders, which spend their entire life cycles in the complete absence of light, our results demonstrated that they could detect light, and light cues may be used to avoid the perilously dry environment outside the cave. The annotation of core PPGs based on transcriptomic data suggests that cave-dwelling Leptonetela spiders have retained a nearly complete set of PPGs as in the entrance spiders. The molecular evolutionary analysis showed strong purifying selection on PPGs of cave-dwelling Leptonetela spiders. Therefore, our study provides evidence supporting the hypothesis that the phototransduction system of cave-dwelling eyeless Leptonetela spiders may have been under purifying selection rather than being a phylogenetic relic. Our results thus refute the neutral hypothesis.

Leptonetela spiders are small cryptozoic spiders that build sheet webs for capturing prey in twilight or lightless environment, such as leaf litter, rotting logs, rock crevices, and caves (31). Light is suggested to be the primary selective force driving the evolution of eyes of cave animals, thus, eyes are often reduced or lost as cave preadaptation in many litter-dwelling arthropods (36–38). Leptonetela spiders have lost anterior median eyes that are generally involved in identifying and stalking prey in spiders, likely due to their twilight or lightless habitats. In addition, cave-dwelling Leptonetela spiders living in lightless deep caves exhibit various degrees of eye reduction (highly reduced or eyeless) compared to their entrance spider relatives that have six intact eyes. Thus, Leptonetela spiders provided an ideal system for studying the evolution of eyes and visual systems.

This study provides evidence demonstrating negative phototaxis in cave-dwelling spiders, a highly diverse group that plays a critical role in cave ecosystems as top predators (23). Negative phototaxis has frequently been found in other subterranean animals. For example, the cave-dwelling carrion beetle Ptomaphagus hirtus that has highly reduced eyes nonetheless displays strongly negative phototaxis and maintains a reduced but functional phototransduction system, as shown by transcriptomic data (13). However, Langille et al. (14) reported that five of six subterranean water beetles completely lacked phototactic responses, and the authors proposed negative phototaxis as a preadaptation to living in permanent darkness for ancestral cave-dwelling animals. We speculate that drought resistance may play an important role in the retention of PPGs in Leptonetela spiders.