The various identities of cells, whether they are in the brain, heart, kidney, or any other tissue, are defined by the genes they expressed. In basic terms, the genes that are active in a cell are transcribed into RNA molecules that are then translated into proteins using tRNA molecules. In the genetic code, three base pair sequences of DNA, or codons, represent amino acids. These amino acids are moved into place by tRNA molecules, which have matching anticodons, to make proteins. There is redundancy in the genetic code as well, in which one amino acid can often be encoded by a few different codons.

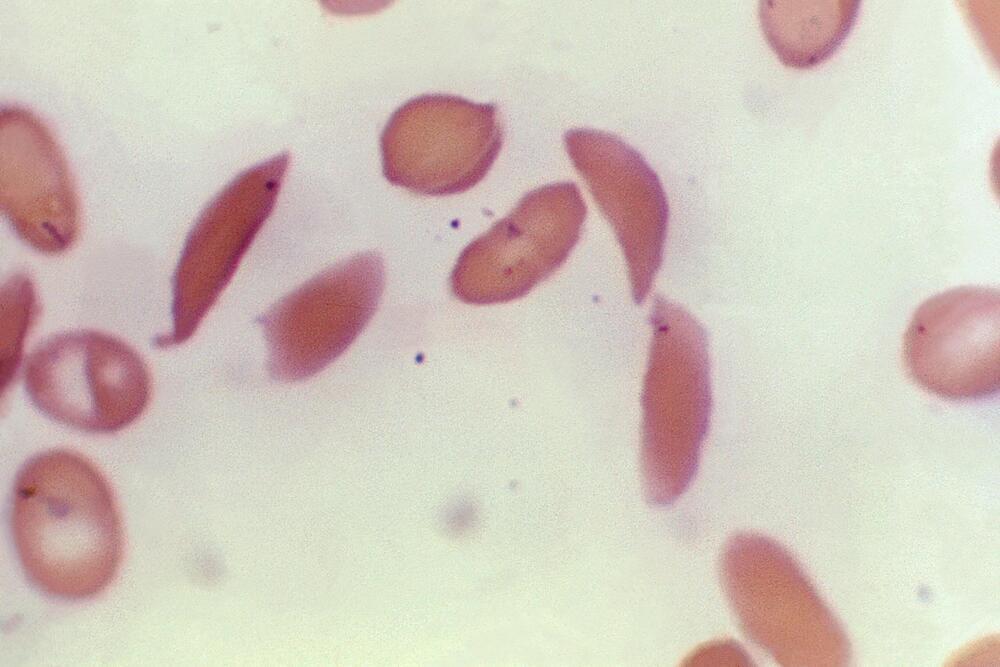

Protein production varies considerably in different cells, and this is especially notable in cells that generate antibodies. These cells often have to spring into action and shift into high gear to generate many infection-fighting antibodies quickly. These antibody producers are B cells, and they often make significant metabolic adaptations when they’re needed.