Metastasis remains the leading cause of death in most cancers, particularly colon, breast and lung cancer. Currently, the first detectable sign of the metastatic process is the presence of circulating tumor cells in the blood or in the lymphatic system. By then, it is already too late to prevent their spread. Furthermore, while the mutations that lead to the formation of the original tumors are well understood, no single genetic alteration can explain why, in general, some cells migrate and others do not.

“The difficulty lies in being able to determine the complete molecular identity of a cell – an analysis that destroys it – while observing its function, which requires it to remain alive,” explains the senior author. “To this end, we isolated, cloned and cultured tumor cells,” adds a co-first author of the study. “These clones were then evaluated in vitro and in a mouse model to observe their ability to migrate through a real biological filter and generate metastases.”

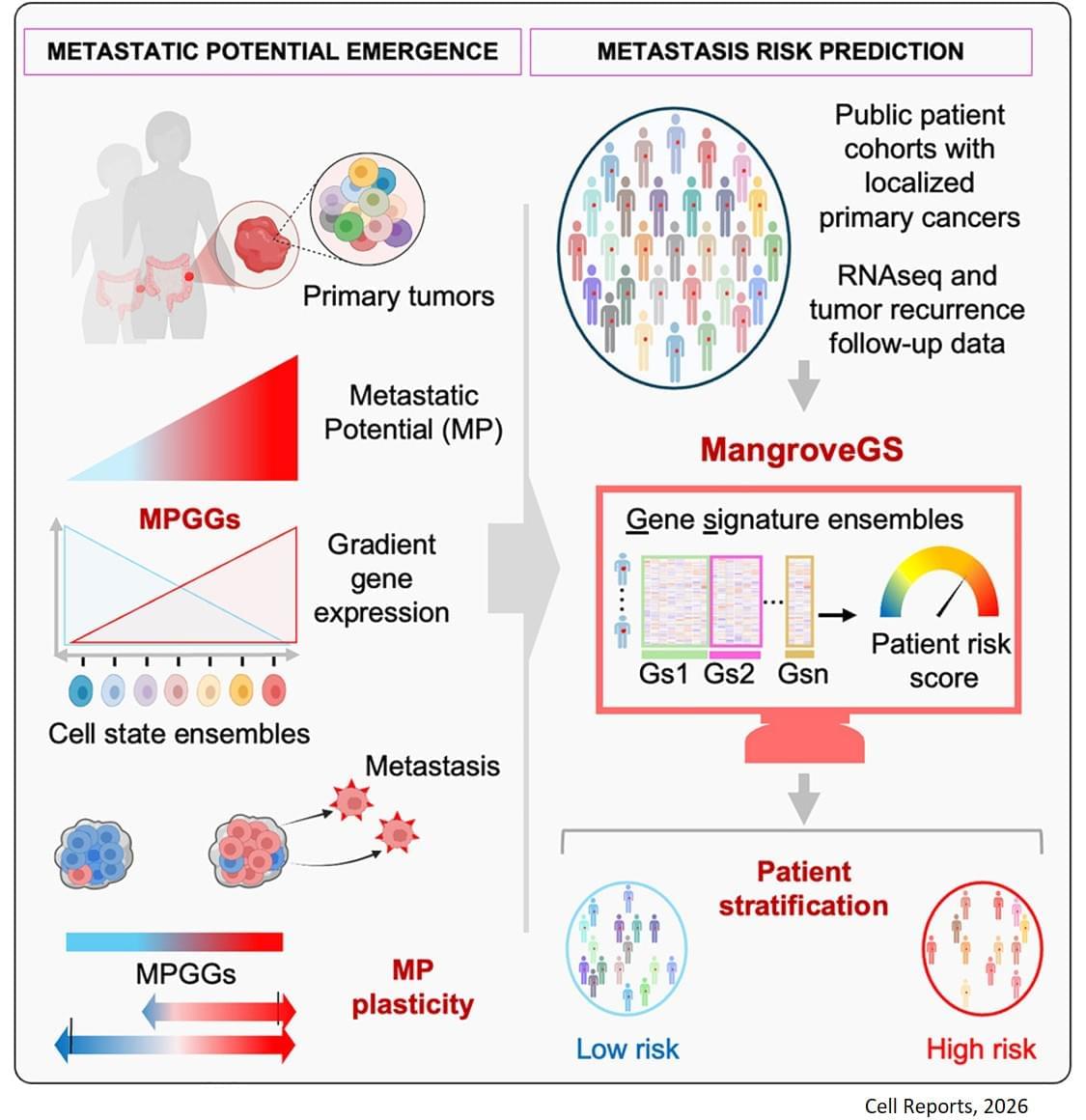

The analysis of the expression of several hundred genes, carried out on about thirty clones from two primary colon tumors, identified gene expression gradients closely linked to their migratory potential. In this context, accurate assessment of metastatic potential does not depend on the profile of a single cell, but on the sum of interactions between related cancer cells that form a group.

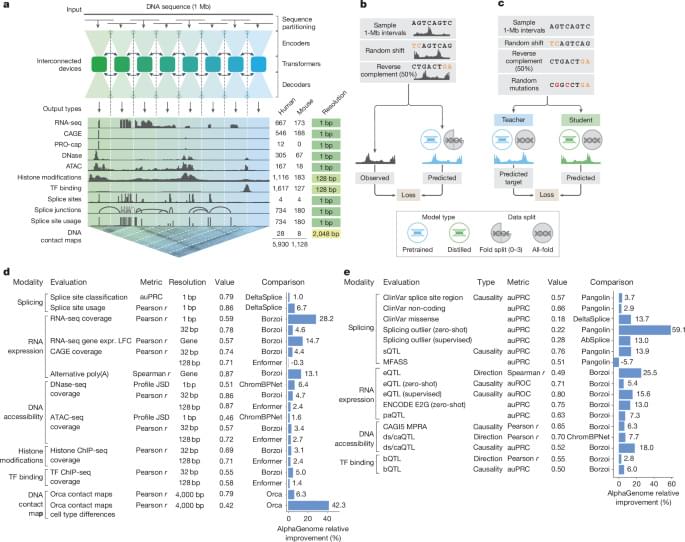

The gene expression signatures obtained were integrated into an artificial intelligence model developed by the team. “The great novelty of our tool, called ‘Mangrove Gene Signatures (MangroveGS)’, is that it exploits dozens, even hundreds, of gene signatures. This makes it particularly resistant to individual variations,” explains another co-first author of the study. After training, the model achieved an accuracy of nearly 80% in predicting the occurrence of metastases and recurrence of colon cancer, a result far superior to existing tools. In addition, signatures derived from colon cancer can also predict the metastatic potential of other cancers, such as stomach, lung and breast cancer.

After training, the model achieved an accuracy of nearly 80% in predicting the occurrence of metastases and recurrence of colon cancer, a result far superior to existing tools. In addition, signatures derived from colon cancer can also predict the metastatic potential of other cancers, such as stomach, lung and breast cancer.

Thanks to MangroveGS, tumor samples are sufficient: cells can be analysed and their RNA sequenced at the hospital, then the metastatic risk score quickly transmitted to oncologists and patients via an encrypted Mangrove portal that has analysed the anonymised data.

“This information will prevent the overtreatment of low-risk patients, thereby limiting side effects and unnecessary costs, while intensifying the monitoring and treatment of those at high risk,” adds the senior author. “It also offers the possibility of optimising the selection of participants in clinical trials, reducing the number of volunteers required, increasing the statistical power of studies, and providing therapeutic benefits to the patients who need it most.” ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.