Imagine a container of tomatoes arriving at the container terminal in Aarhus. The papers state that the tomatoes are from Spain, but in reality, we have no way of knowing if that is true.

That is, unless we take a sample and have it analyzed in a laboratory, where scientists use DNA markers to determine whether the tomato is Spanish, South American or Chinese. This is both time-consuming and expensive.

But thanks to a scientific breakthrough, we will be able to examine tomatoes a lot quicker and cheaper, using special light producing proteins and our phones camera. Not right now, but in the near future.

The results were recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

“We have figured out how to instruct the proteins to generate light when specific DNA sequences appear. This could be used, as in the example with the tomatoes, but could also be useful in the healthcare sector, agriculture, or the pharmaceutical industry to analyze samples easily and cheaply,” the senior author explains.

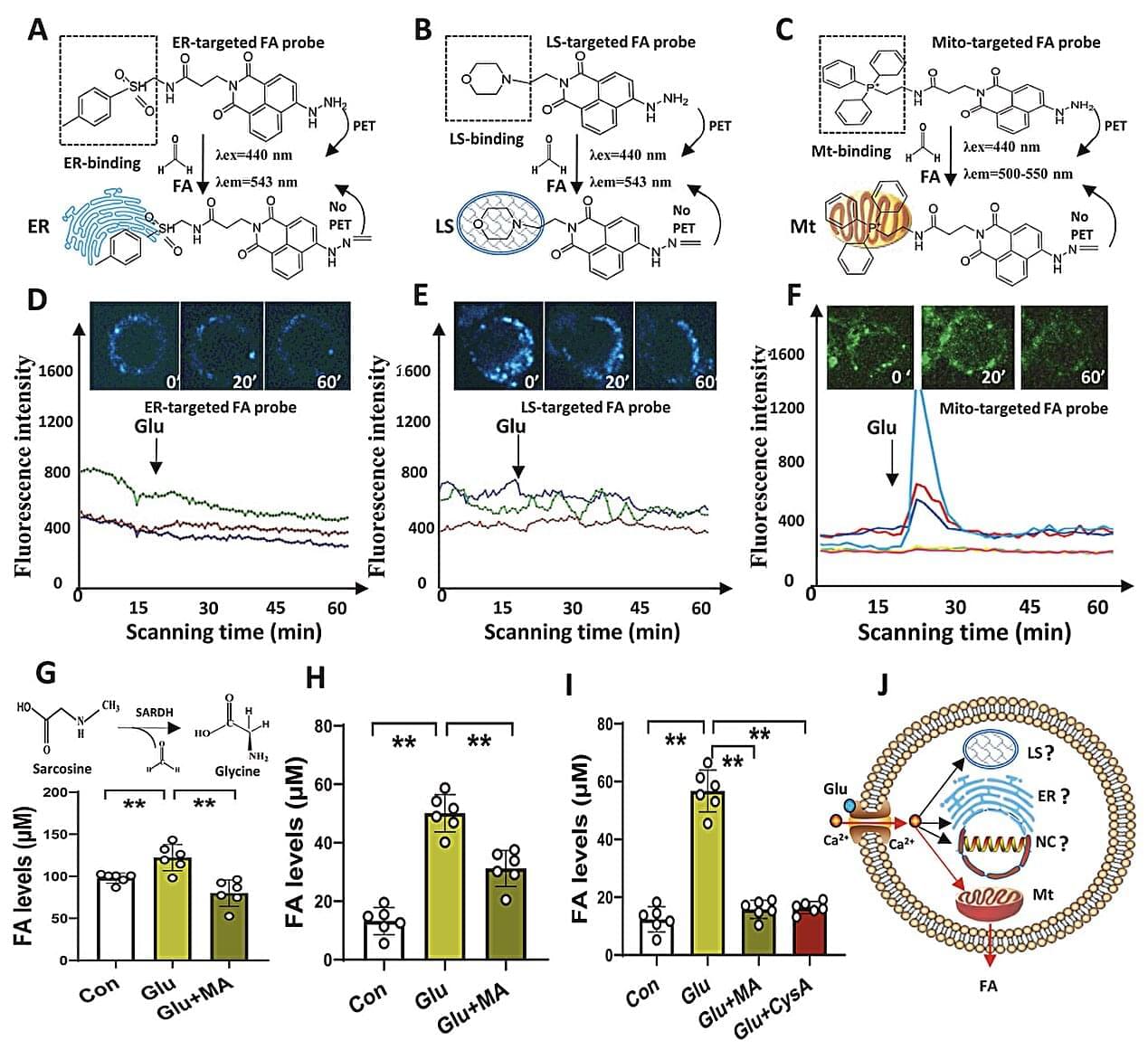

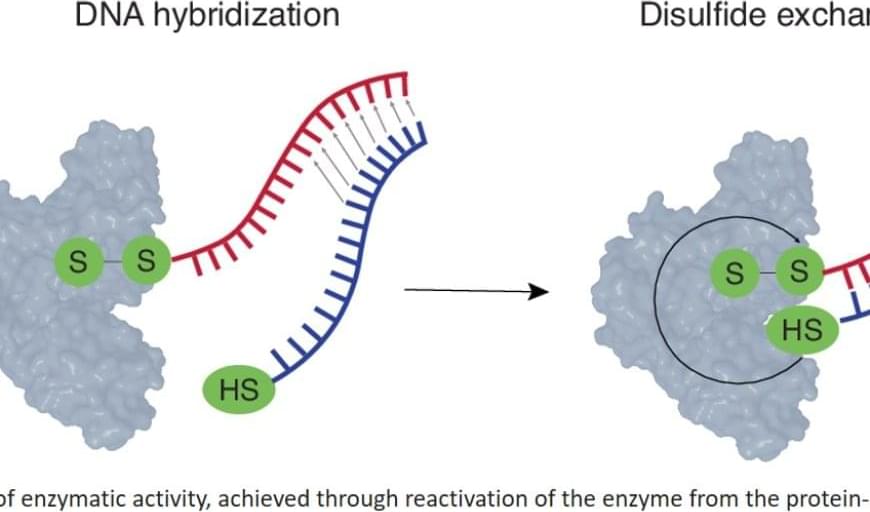

The authors did this via “thiol switching”, using thiolated oligonucleotides: a protein is inactivated by conjugation to an oligonucleotide via a disulfide linkage; hybridization of the thiolated complementary oligonucleotide ensues disulfide exchange, the liberation of the enzyme, and the activation of enzymatic catalysis. In doing so, the researchers couple the most specific recognition event (hybridization) to the most effective tool of signal amplification (catalysis).

“Our primary goal is to control the activity of molecules in space and time, inside and outside of the cell. Specifically we focus on enzymes that can create ATP, which is the cell’s fuel, and polymerases, which the cell uses to build RNA and DNA.”