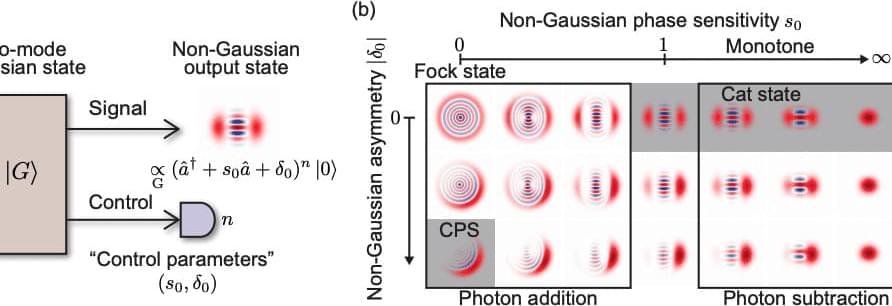

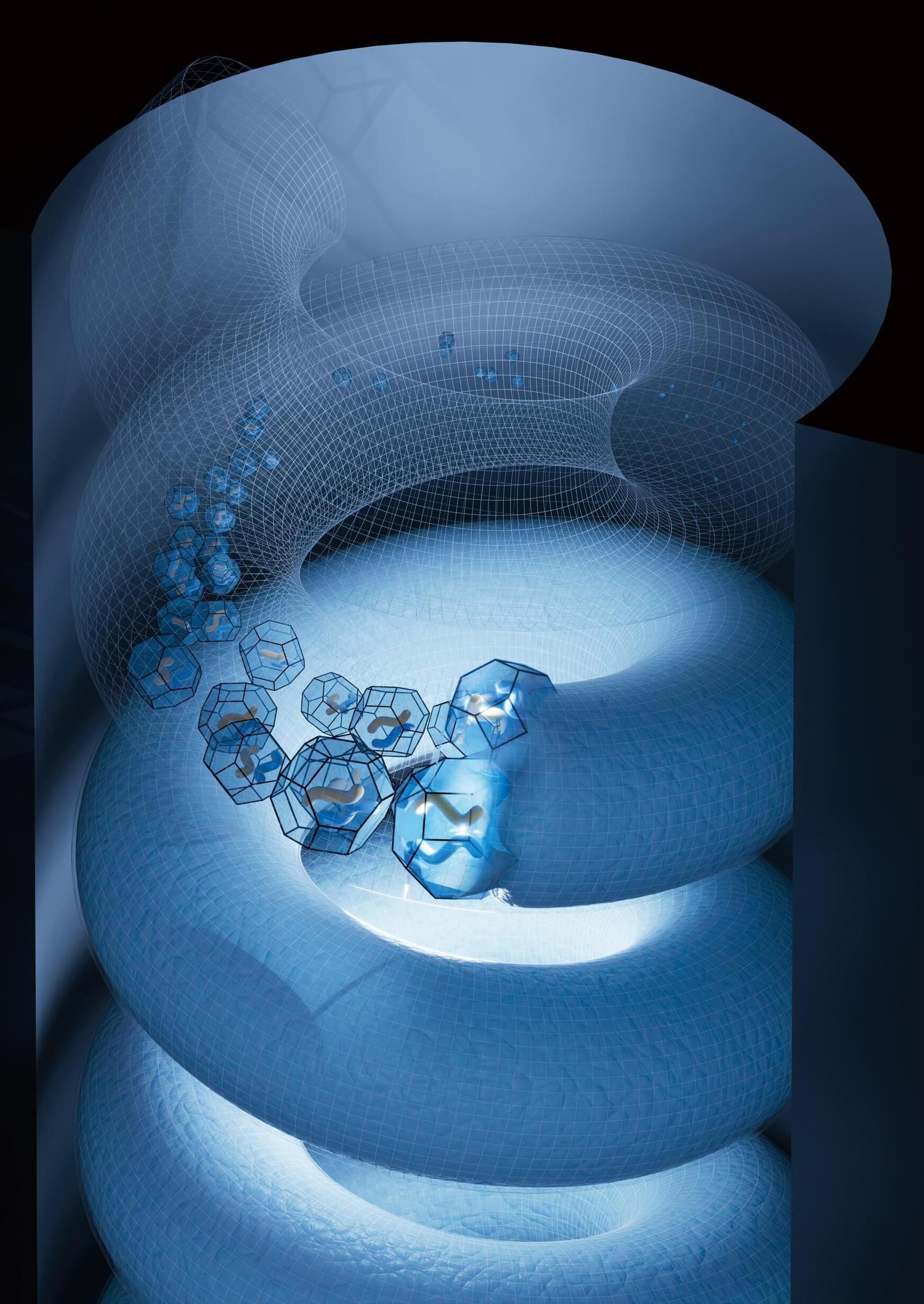

Non-Gaussian states of light represent a crucial component for advancements in quantum technologies, holding immense potential for universal computation, robust error correction, and highly sensitive sensing, yet creating these states remains a significant challenge. Fumiya Hanamura, Kan Takase, and Hironari Nagayoshi, along with their colleagues, now present a new approach to overcome these hurdles, introducing ‘non-Gaussian control parameters’ that offer a more effective way to measure and optimise the generation of these complex states. This method moves beyond traditional benchmarks, such as stellar rank, by providing a continuous and practical measure of non-Gaussianity, and importantly, dramatically reduces the resources needed for successful state creation. Demonstrations across a range of states, including cat states and GKP states, reveal that this technique cuts required photon detections by a factor of three and boosts preparation probability, paving the way for more feasible and scalable quantum technologies and fault-tolerant computation.

Researchers have developed a new method for generating complex states of light that significantly reduces the resources needed for advanced technologies like quantum computing and sensing, achieving a threefold reduction in required measurements and a substantial increase in success rates across various light states.