3D printing is a simple way to create custom tools, replacement pieces and other helpful objects, but it is also being used to create untraceable firearms, such as ghost guns, like the one implicated in the late 2024 killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson.

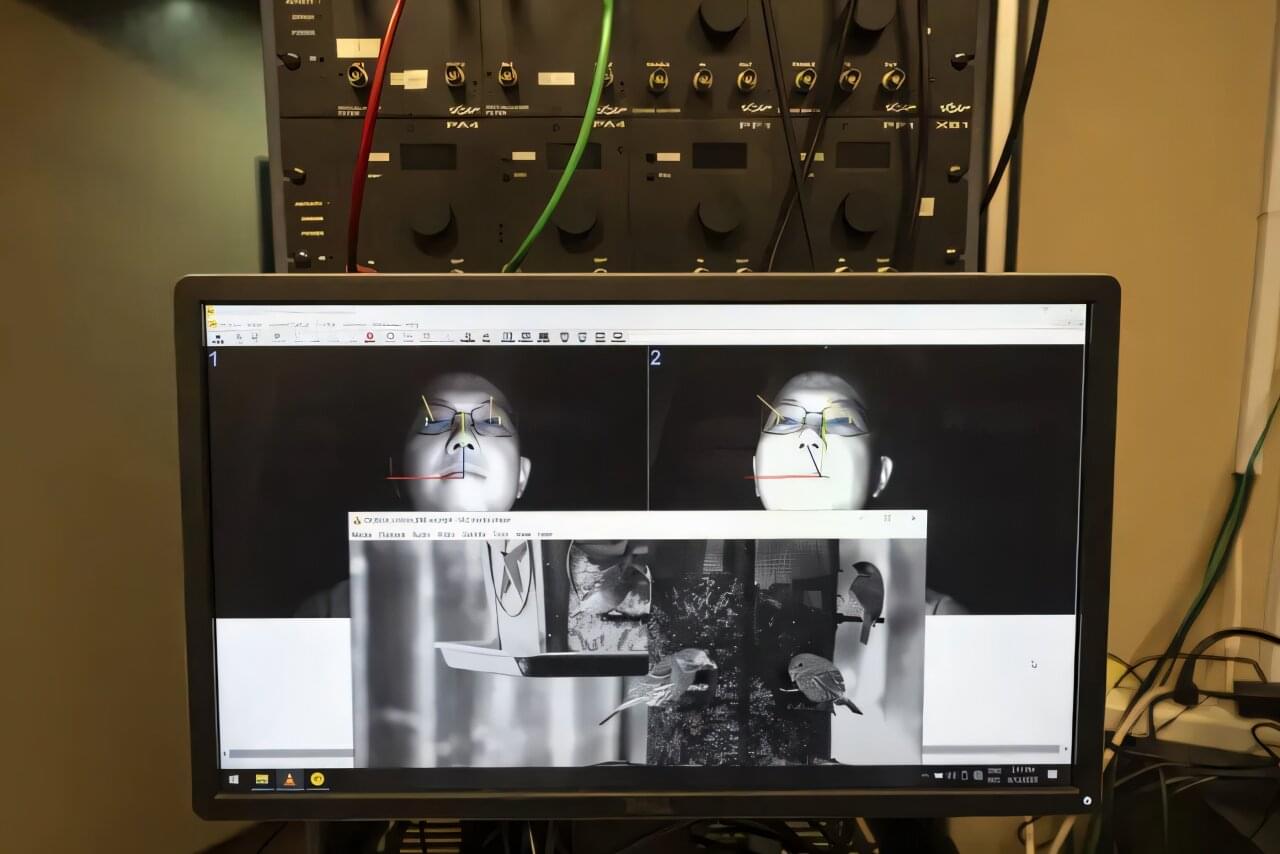

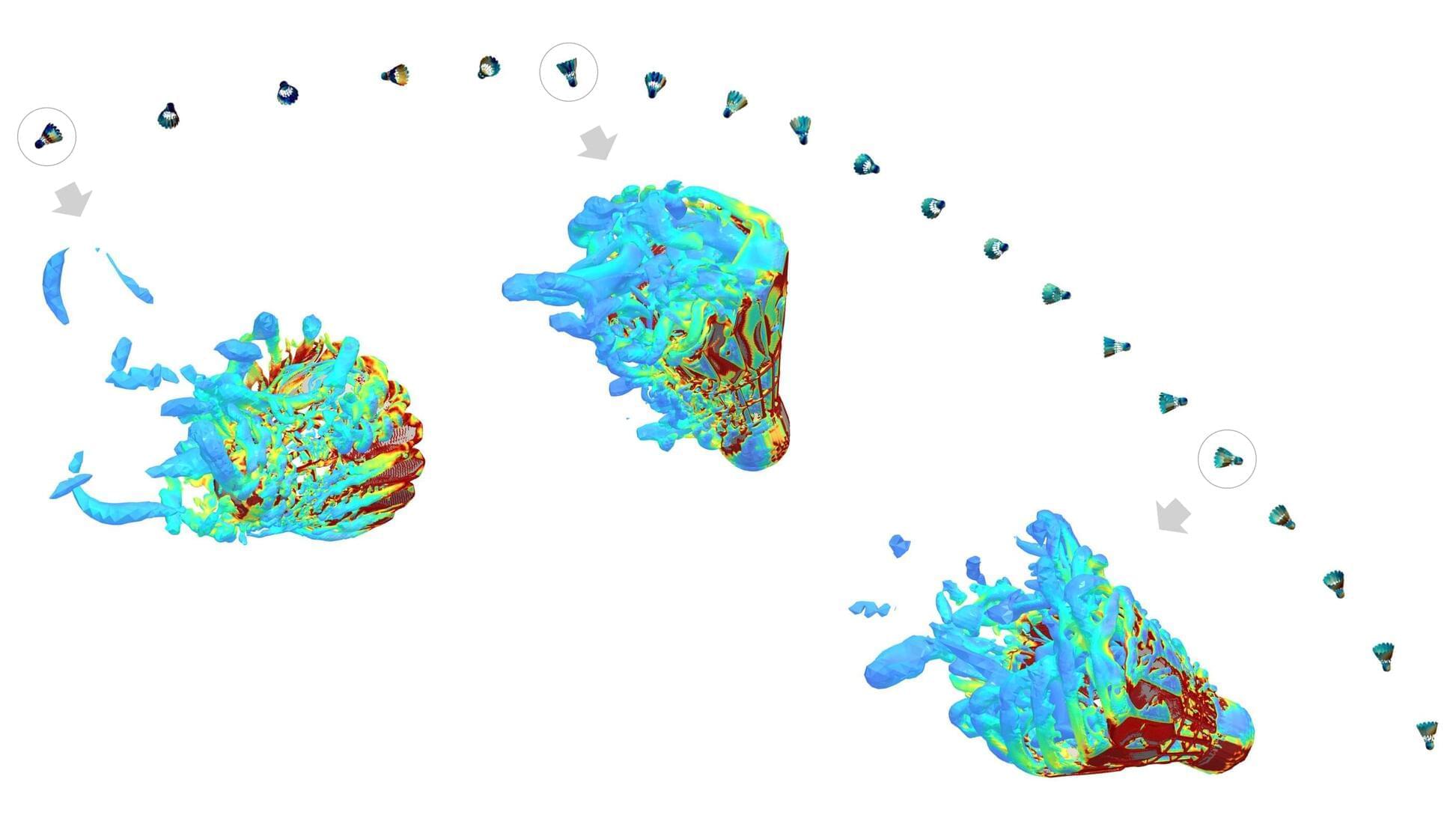

Netanel Raviv, assistant professor of computer science & engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, led a team from the departments of Computer Science & Engineering and Biomedical Engineering that has developed a way to create an embedded fingerprint in 3D-printed parts that would withstand the item being broken, allowing authorities to gain information for forensic investigation, such as the identity of the printer or the person who owns it and the time and place of printing.

The research will be presented at the USENIX Security Symposium Aug. 13–15, 2025, in Seattle. The first authors of the paper are Canran Wang and Jinweng Wang, who earned doctorates in computer science in 2024 and 2025, respectively. The research is published on the arXiv preprint server.