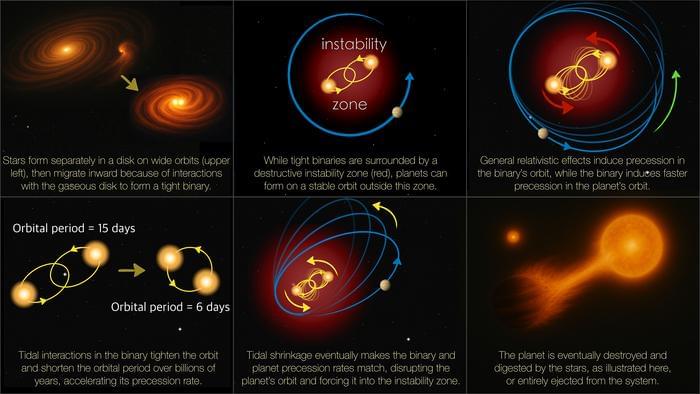

“Two things can happen: Either the planet gets very, very close to the binary, suffering tidal disruption or being engulfed by one of the stars, or its orbit gets significantly perturbed by the binary to be eventually ejected from the system,” said Dr. Mohammad Farhat.

Why is it so rare to find exoplanets orbiting two stars, also called circumbinary planets (CBPs)? This is what a recent study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters hopes to address as a team of researchers investigated the celestial processes responsible for the formation and evolution of CBPs. This study has the potential to help scientists better understand solar system and planetary formation and evolution, which could narrow the search for life beyond Earth.

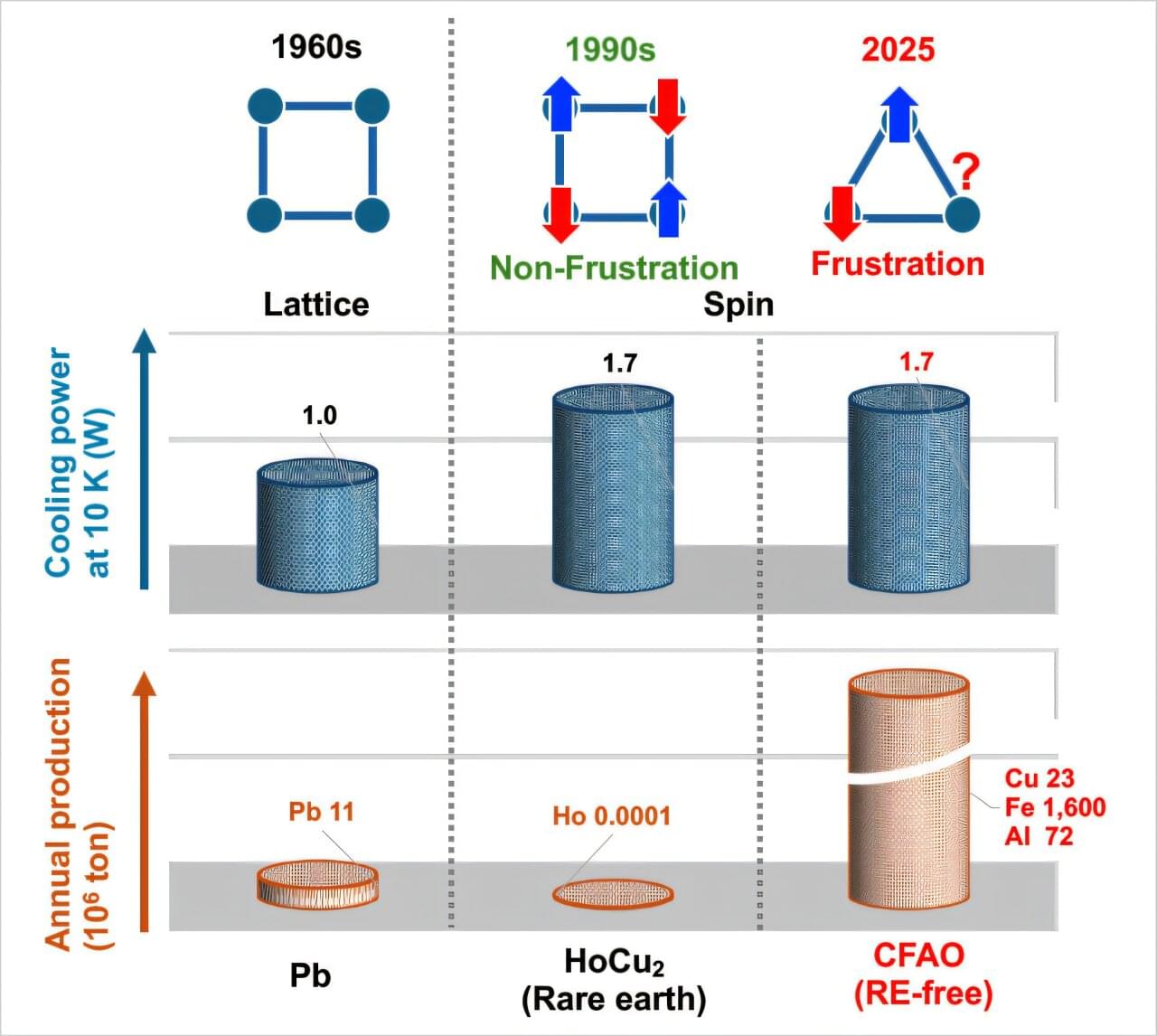

For the study, the researchers used a combination of computer models and Einstein’s theory of relativity to simulate the formation and evolution of CBPs. For example, the researchers explored the interaction between the CBP and its binary star, resulting in one of three outcomes: stable orbit, ejection, or consumption by the binary star. The reason Einstein’s theory of relativity was used as part of the study was because it calls for objects to have their orbit perturbed the closer they orbit to a larger object, like a star.

A common example that’s used for the theory is of a trampoline with objects falling inward when a large body is in the middle of it. Essentially, stars have “instability zones” where planets get consumed if they orbit too close. In the case of CBPs, the astronomers found that of the 14 known CBPs out of more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, 12 orbit just beyond the instability zone and none of the 14 have orbits less than seven days. The researchers concluded that a common phenomenon in astronomy called the three-body problem is responsible for the lack of CBPs.