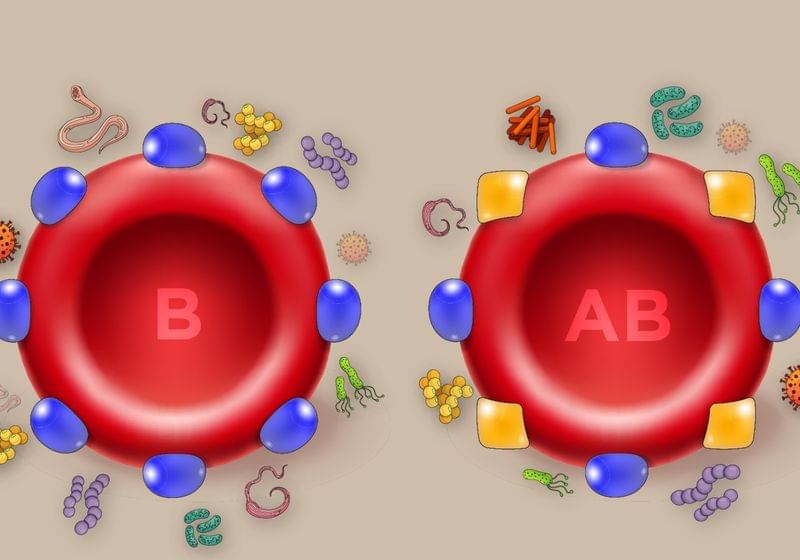

Humanity’s microscopic foes may be to blame for the ABO polymorphism.

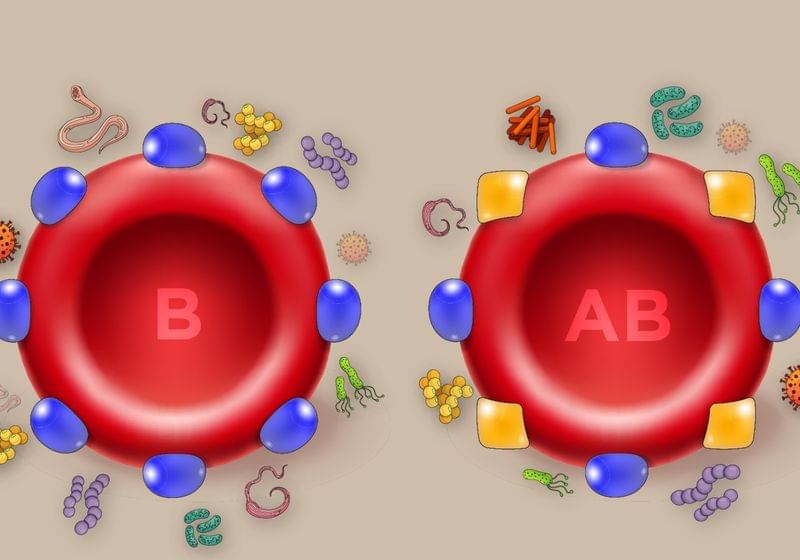

A new brain-mapping tool just dropped!

LA JOLLA—Scientists at the Salk Institute are unveiling a new brain-mapping neurotechnology called Single Transcriptome Assisted Rabies Tracing (START). The cutting-edge tool combines two advanced technologies—monosynaptic rabies virus tracing and single-cell transcriptomics—to map the brain’s intricate neuronal connections with unparalleled precision.

Using the technique, the researchers became the first to identify the patterns of connectivity made by transcriptomic subtypes of inhibitory neurons in the cerebral cortex. They say having this ability to map the connectivity of neuronal subtypes will drive the development of novel therapeutics that can target certain neurons and circuits with greater specificity. Such treatments could be more effective and produce fewer side effects than current pharmacological approaches.

The study, published on September 30, 2024, in Neuron, is the first to resolve cortical connectivity at the resolution of transcriptomic cell types.

The LEV Foundation is a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the field of rejuvenation biotechnology with the goal of reversing biological aging. Under the leadership of renowned gerontologist Aubrey de Grey, the foundation focuses on conducting early-stage research on animals, specifically testing combination therapies that aim to dramatically extend lifespan. LEV Foundation stands out in the aging research community by targeting middle-aged mice, developing treatments that could one day be applied to humans, helping achieve longevity escape velocity — the point at which aging can be controlled through medical interventions.

Pathogen encounter can result in epigenetic remodeling that shapes disease caused by heterologous pathogens.

The therapeutic potential of antigen-independent innate immune memory (IIM) is of particular relevance in the context of respiratory viruses with pandemic potential. Lercher et al. find that antiviral IIM in alveolar macrophages following SARS-CoV-2 infection ameliorates disease caused by a secondary unrelated pathogen, influenza A virus.

Researchers have uncovered how hormones profoundly affect our immune systems, explaining why men and women are affected by diseases differently.

Scientists from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and Imperial College London have shown for the first time which aspects of our immune systems are regulated by sex hormones, and the impacts this has on disease risk and health outcomes in males and females.

It is well established that diseases can affect men and women differently, due to subtle differences in our immune systems. For example, the immune condition systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is nine-times more likely to affect women, or with COVID-19, males are known to have a greater risk of acute first-time infections, while females have a greater risk of long-COVID.

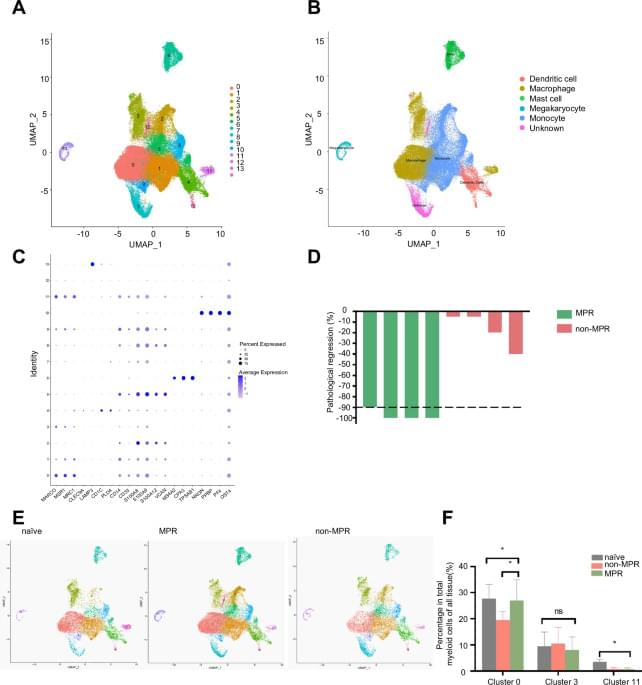

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) immunotherapy facilitates new approaches to achieve precision cancer treatment.

Zhang, D., Wang, M., Liu, G. et al. Novel FABP4+C1q+ macrophages enhance antitumor immunity and associated with response to neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in NSCLC via AMPK/JAK/STAT axis. Cell Death Dis 15, 717 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-07074-x.

U.S. researchers developed CheekAge, a tool that reliably estimates mortality risk.

Researchers in the United States have created a next-generation tool named CheekAge, which uses methylation patterns found in easily obtainable cheek cells.

In a groundbreaking discovery, the team has demonstrated that CheekAge can reliably estimate mortality risk, even when epigenetic data from different tissues are utilized for analysis.

Epigenetic markers are chemical changes to DNA that don’t alter the genetic code but can affect how genes work. Methylation is one such change, often linked to aging. Scientists use these patterns to create “age clocks” that estimate biological age, revealing how fast someone is aging.

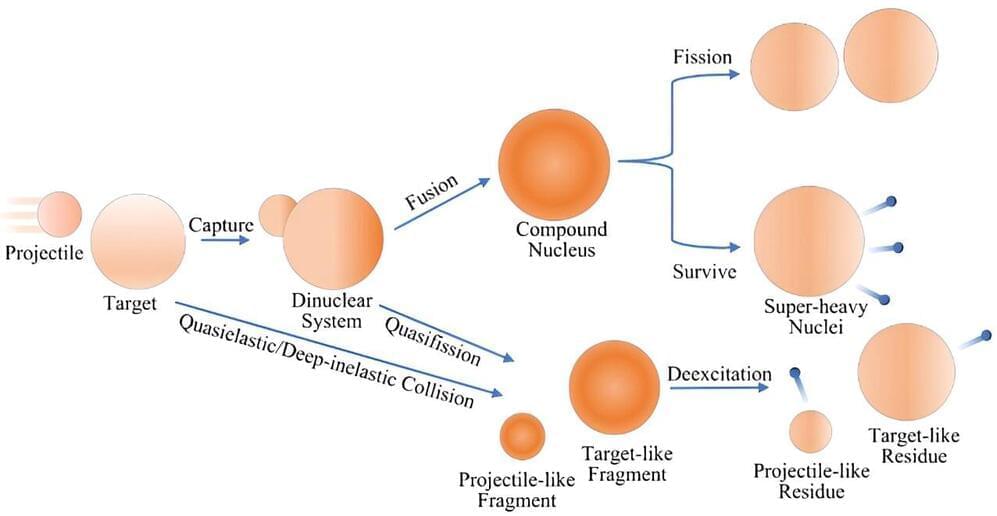

The improved accuracy of MNT reaction predictions provided by this model could facilitate the production of isotopes that are difficult to generate using other methods. These isotopes are valuable for scientific research and medical applications, such as diagnostics and treatments. According to Prof. Zhang, the goal is to keep the model comprehensive yet practical for experimental use.

This development represents a step forward in nuclear physics, contributing to the understanding of exotic nuclei production through MNT reactions. Further refinement of the model may enhance its utility in guiding future research and improving rare isotope production processes.

This research was conducted in collaboration with Beijing Normal University, Beijing Academy of Science and Technology, and the National Laboratory of Heavy Ion Accelerator of Lanzhou.

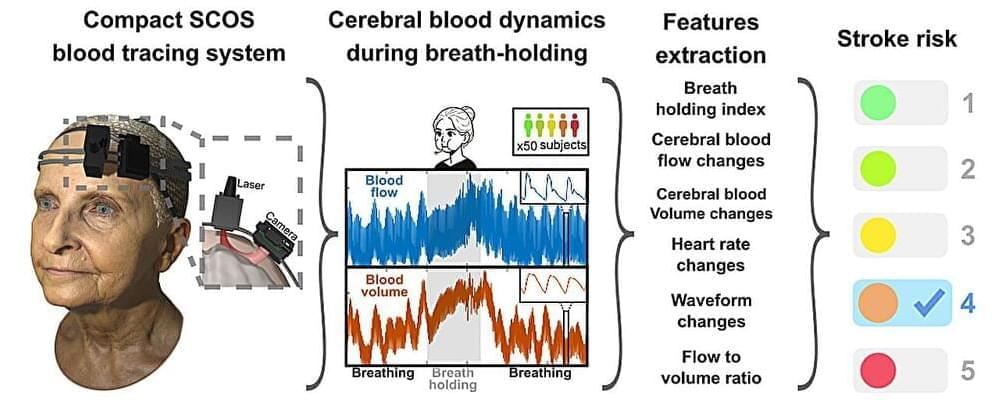

A team of researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC and California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have developed a potential new way to measure a person’s stroke risk that is cost-effective and noninvasive, akin to a cardiac stress test. If validated through further tests, the device could transform stroke care, making early detection of increased risk a standard part of medical exams around the world.

New steps have been taken towards a better understanding of the immediate and long-term impact of COVID-19 on the brain in the UK’s largest study to date.

Published in Nature Medicine, the study from researchers led by the University of Liverpool alongside King’s College London and the University of Cambridge as part of the COVID-CNS Consortium shows that 12–18 months after hospitalisation due to COVID-19, patients have worse cognitive function than matched control participants. Importantly, these findings correlate with reduced brain volume in key areas on MRI scans as well as evidence of abnormally high levels of brain injury proteins in the blood.

Strikingly, the post-COVID cognitive deficits seen in this study were equivalent to twenty years of normal ageing. It is important to emphasise that these were patients who had experienced COVID, requiring hospitalisation, and these results shouldn’t be too widely generalised to all people with lived experience of COVID. However, the scale of deficit in all the cognitive skills tested, and the links to brain injury in the brain scans and blood tests, provide the clearest evidence to date that COVID can have significant impacts on brain and mind health long after recovery from respiratory problems.