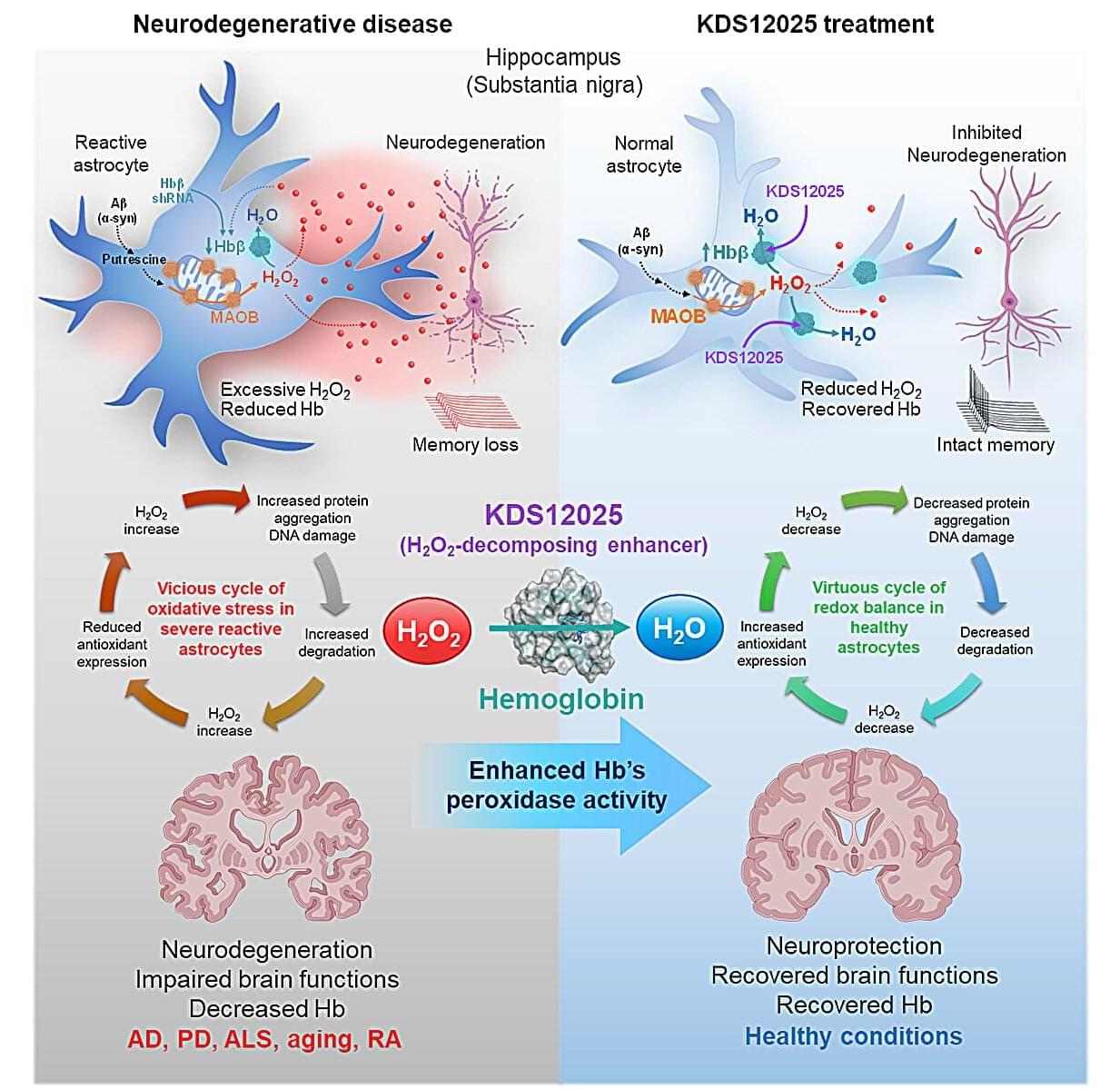

Hemoglobin, long celebrated for ferrying oxygen in red blood cells, has now been revealed to play an overlooked—and potentially game-changing—antioxidant role in the brain.

In neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and aging, brain cells endure relentless damage from the aberrant (or excessive) reactive oxygen species (ROS). For decades, scientists have tried to neutralize ROS with antioxidant drugs, but most failed: they couldn’t penetrate the brain effectively, were unstable, or indiscriminately damaged healthy cells.

This new study, led by Director C. Justin Lee of the Center for Cognition and Sociality within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in Daejeon, South Korea, set out to identify the brain’s own defenses against a particularly harmful form of ROS—hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The study has been published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.